|

Charles E. Rice (1929 - 1986) lived a good part of his life in mountain areas of Georgia and Tennessee. He grew up on Missionary Ridge in Northern Georgia, almost in the shadow of Tennessee's Lookout Mountain. The nature and culture of the Ridge enriched his childhood and informed many of his essays and stories, which his son Philip collected in The View from My Ridge. As a clergyman, Charles Rice held several pastorates in Tennessee, the last as rector of Trinity Episcopal Church in Gatlinburg. During the Gatlinburg years, he wrote "The Waiting Mountains." One of the selections in Section Two of The View from My Ridge, this essay was first published in the Tennessee Conservationist in 1985.

We are grateful to Phil Rice and Canopic Publishing for providing this piece and for giving us an opportunity to review his father's book.

The Waiting Mountains

Charles E. Rice

The gods of time have autographed the earth's crust with monumental designs. Among them stand those immense strokes we call the Great Smokies. From thousands of feet above, these mountainous inscriptions stand out like braille on a vast, rippled scroll. And, as with the writings for the blind, mountains must be touched and followed to tap their secrets. What Wordsworth called "the voice of the mountains" can be heard only as it is felt.

All great mountains make their imprint upon the sensibilities and destiny of the human race. The Smokies rise well to this conversation with history. For millions of years before man stood in their shadows, these patient peaks waited for him. Today, people venture by multitudes toward this mountain realm. And the Smokies in their seasonal garments still wait . . . as if for the first murmur of human awe.

The foothills of the Great Smokies fan out and probe the surrounding country in a maze of dips and turns. These both beckon and forbid the traveler. From miles away the silhouette of the peaks on a clear day steadily salutes and invites the beholder. Moving into the foothills, however, these same peaks flash into view only to retreat again behind the modest covering of the slopes beneath them.

The mountains-their vegetation, wildlife and even their weather-offer but a limited and temporary welcome. Like the natives who know them best they may tender hospitality but rarely intimacy. Seemingly friendly wooded slopes, quiet hollows, and singing waters can still mislead and disorient the unwary. In every generation wayfarers have gone unto these hills never to return.

Winding stretches of concrete and asphalt have been poured along some of the early trails through valley and gap. These smooth but fragile byways are like bridges spanning a mighty river. They barely touch and never subdue the wild spirit below and to either side of them. Mountain roads, at best, remind the user that he is surrounded by impassable mountain mysteries . . . or, that he has an exit. After all, even the sign of a "Motor Nature Trail" suggests more than it can deliver.

The proud Smokies possess an array of skills. These matchless mountains can excite, seduce, inspire, calm, exercise, hypnotize, aggravate, isolate, revive or kill man or beast. These tremendous mounds of time also have bred their artists and warriors, cults and castes, common folk and chieftains. The long shadows of the mountain evening cover all who come or go with mute indifference to rank or reputation. Neither do these heights weep whether tree or man is felled. The natives of these highlands know well this solemn mountain "truth."

II

From all over the world people come to the Smokies. Some stop short. Tourists frequently ask shop clerks of Gatlinburg or Pigeon Forge, "What is there to do or see around here?" Some of these surely have not come to the Smokies but rather from something, somewhere. Or, perhaps, they seek the mountains but the mere sight of Mt. LeConte from a motel window satisfies their quest. That great, sharp summit, snow-crowned much of the year, does cast a spell from any angle.

The vantage point shapes and reshapes any view or encounter with these many-splendored mountains. Different temperaments, tastes, trails, or times make for a chemistry of an infinite variety of visions. From top to bottom this mountain world throbs with clues and signals for the attentive. Move in any direction but a few paces or ponder a new question and the mood can change.

The paved entrances to the Great Smokies are relatively few but, some would insist, ample. Main routes converge from North Carolina through Asheville and Cherokee. From Tennessee the gateway opens by way of Sevierville or Townsend. Snows in higher elevations close some passageways in winter. By foot, entry into the mountains is limited only by physical stamina, caution, and common sense.

Human nature, regardless of the route or vehicle, approaches this mountain reality with more than a fixed destination. Mankind from the beginning has brought its mixed baggage of faith and folly, greed and grace. For one and all the mountains wait. Unmoved these towers of time stand massive and majestic before the just and the unjust alike. But, while the mountains do not discriminate, they guard and convey their mysteries jealously. The "voice of the mountains" is heard best by those who expect what can be found only in the mountains.

III

Mountains lure the human spirit in every generation. Ocean depths, starry heavens, wind-swept deserts and arctic masses also tempt the imagination. Indeed, all creation makes its bid for the rapt attention of the only mortal creature capable of awe and wonder. But great mountains not only loom higher in sight. They stand out in history as watersheds and way stations in the whole human story.

Poets, prophets, mystics, monks, generals, engineers, and plumbers each and all have their reasons for "seizing the high ground." The challenge goes deeper still. Mountains move men. They speak to the human soul with an eloquence barely shy of religion . . . if shy at all. They intimate what they can never exhaust or define: the very idea of the holy.

The great religions of the world, East and West, sprang from mountain anchored roots. They draw from and feed upon the lore and legacy of mountain-top visions. The sacred literature of Jew and Christian and kindred religions echo with gratitude for the "everlasting hills." For thousands of years those reverent poets and scribes found the mountains a symbol of stability as well as of grandeur.

And mountains also beckon all peoples to identify and size up their gods. Wherever we take our own handiwork too seriously, mountains rise before us as sobering sentinels of a reality above and beyond us. Their endurance, vastness, dark recesses, roaring waters-and their stillness mock as petty and passing the fever and folly of civilizations.

The Great Smoky Mountains offer rest and recreation to all comers. They invite the artist's brush and the camera's eye among all other disciples of nature's beauty and marvel. They also invoke a religious reflex even among some who are too worldly wise for such primitive touches. These mountains ask no creed or contribution. But they call forth a sense of creatureliness from those who consider them for a while. They confront us with new ways of measuring life-a keener sense of proportion.

The Smokies seem to know, even if we don't, that we have not progressed in our capacity for humility, beauty, and awe. We stand in such matters too often behind those sons of men who first climbed these wooded steeps. We walk behind those prehistoric tribes as well as behind those later, highly appreciative Cherokees when we walk among these hills. We trail, as well, those Anglo-Saxon late-comers who boldly settled-but never finally conquered-this peculiar reach of earth and sky. And the Smokies still wait.

The View from My Ridge, in which "The Waiting Mountains" appears, can be ordered online from Canopic Publishing at www.canopicjar.com

Authors | Home | Top

Phil Rice is an essayist, a poet, the founder of the independent press Canopic Publishing, and editor of Canopic Jar, an online forum for multi-media expression with emphasis on literary efforts. www.canopicjar.com He recently developed Juke Jar, an online forum for literary and visual art about music. www.jukejar.com

In "Experiencing Winwood," which appeared in the first issue of Juke Jar, Rice traces the career milestones of rock legend Steve Winwood that have become artistic landmarks for Rice's own life.

Experiencing Winwood: A Musical Memoir in 11 Minutes and 41 Seconds

Philip Rice

Often lost and forgotten, the vagueness and the mud . . .

(from the song "Empty Pages" by Winwood/Capaldi)

The presents under the tree in 1974 have all faded from my memory, joining the other lost images from the receding past-except for one. There was a flat, 12" x 12" package from my brother Hal, one of many such shaped presents I would receive from him over the years. As I ripped off the paper I was confronted by a huge face with angular cheekbones dominating the brown cover of a double record album. There was only one word on the front, in big letters lined up vertically on the spine edge: WINWOOD.

At first I didn't know what to make of the album, which Hal explained was a collection of different songs from different groups, all featuring a guy named Steve Winwood. The ones to pay particular attention to, according to Hal, were "Goodbye Stevie," which featured Winwood on piano, and "Stevie's Blues," which showed his prowess on organ and guitar. With that bit of advice my brother returned to his hideaway in the basement and left me to decipher the music for myself. I was 14 and still listening to my Beatle and Creedence Clearwater Revival records over and over again, and feeling no need to branch out. But now there was a new window open, and I was being drawn closer to the sill.

My electronic listening options in those days were limited to my own tiny record player or the family "hi-fi," a rectangular wooden box encasing a stereophonic amplifier, a turntable, and 2 speakers. When the living room was empty, I would plug my headphones into the hi-fi, lie down on the floor, close my eyes, and focus intently on the sounds bouncing out of the tiny speakers. I did this a few times with the Winwood album and discovered that the songs on the first record were catchy and the sort that my 14-year-old ears could easily grasp. The second record contained songs that I wasn't quite ready for, despite the vague familiarity of some of the cuts, such as "Sea of Joy" and "Medicated Goo," which I had no doubt heard during the years I shared a bedroom with my brother. All in all, the collection was difficult for me to digest, and I was slow to reach for Winwood during these listening times. But I was already convinced that it contained something special.

The next year I made the trek from Nashville to Sewanee Academy, a boarding school located on Monteagle Mountain about 90 miles away from my home. Stuffed in my trunk of personal belongings were my 15 or so albums, but I didn't have my own stereo and was therefore at the mercy of friends to allow me the use of their sound machines. I found that most of my records were suspect in the eyes of my peers and that my tastes were apparently out of step with the current popular tunes. Heavy Metal and Southern Rock (which held little interest for me despite, or maybe because of, my Southern roots) were enjoying great popularity among my friends, songs by Elton John and Peter Frampton and the like dominated the top-40 stations, and the artless sounds of disco permeated the clubs and dancehalls. Winwood was not on the playlist, so the album stayed tucked in a drawer despite my yearnings to further explore the music.

After a year at Sewanee I had managed to get in enough trouble to convince my parents to save their money and take their chances with the public schools. I bought my first stereo that summer, and the first record of my Winwood album found a permanent home. Through the Spencer Davis Group I began to discover the "blues," completely blind to the irony of having a white teenager from Birmingham, England introduce me to a music form that had been scratched out a few decades earlier by black folks living about three hours down the highway in the Mississippi delta. Then one day one of my best friends at school was forced to get rid of all of his music by his parents, so he pretended to toss the items in the trash but instead gave the whole batch to me. Included in the grab-bag was an eight-track tape called Welcome to the Canteen, which featured Steve Winwood and a bunch of other names I didn't recognize. I listened to that tape until it met the fate of all 8-tracks-snapping and disappearing into the bowels of the stereo.

For several weeks I found that whatever I was doing or wherever I was going-walking to school, riding my bicycle, etc.-I had this incessant little groove going through my head. It was the bass-line from a song called "40,000 Headmen" on Welcome to the Canteen. The lyric was something about running from a. . .smoking a cigarette and dodging. . . hell, I didn't know what, but it sounded cool, and I could relate to the words even if I didn't completely follow the plot, but mainly I could feel the groove. I discovered that the music itself could take me on a journey regardless of the lyrics. Soon I could separate and rejoin the sounds of each instrument in my head, and Winwood's vocal was functioning as another instrument within the groove itself. From that point on I would experience music on a holistic level beyond the lure of words or lyrical hooks.

As a senior in high school I had a job as a stock boy for Cain-Sloan's, a department store that catered to Nashville's social elite. One afternoon as I was merrily buzzing my way through a work day I overheard a song that featured a familiar voice. I went directly to the record department and discovered that, indeed, Steve Winwood had released a new album, his first as a solo artist. I bought the album immediately, and it became a fixture on my turntable for many months. Oddly, I was the only person I know who bought that album in its first run, although now it seems to have achieved "lost masterpiece" status. That same year I spotted an album called Go in a record shop window. The name "Winwood" was displayed on the cover, so I bought it. The music, composed mostly by Japanese artist Stomu Yamashta, was wonderfully bizarre to my ears, full of synthesizers and a wide assortment of percussion sounds. The album was the musical story of a journey through space-I think-and as far as I am concerned it surpasses any of the Pink Floyd "tripping" music of the seventies. The ensemble, besides Winwood, included drummer Michael Shrieve, jazz guitarist Al DiMeola, and bassist Rosko Gee, among others. Again, I was mesmerized by music that remained unheard of by my schoolmates. I was set apart in my own little world, and the music Steve Winwood was introducing into my life made that little world seem open to infinite possibilities.

II

No album characterized my freshman year at Maryville College in 1978 better than Traffic's The Low Spark of High Heeled Boys, which I had discovered seven years after its initial release. I played the album over and over, particularly the first side, until I could hear each thump and tap, and I was amazed that every space was filled-everything seemed so rhythmic and perfectly balanced and yet somehow spontaneous. I also began to feel the spiritual qualities of the music instead of clinging to the rhythmic and lyrical surface. No longer was the art form of music just about songs. As I read the literature and history lessons placed before me in the classroom, the flowing Traffic music living in my head described how I wanted my budding intellectualism to develop. The Beatles and other pop artists still covered my romantic desires just fine, but the real and ethereal worlds were squarely in the hands of Steve Winwood, Jim Capaldi, Chris Wood, and their various musical companions.

Winwood, by this time, was clearly a rock n roll legend of sorts, a fact that went largely unrecognized by my college peers. Then, usually after a summer break or a long weekend at home, some Winwood-convert would come bursting into my room proudly waving a new discovery from the record store bins. In this way I was introduced to Traffic on the Road, a magnificent album recorded live in 1973. Unlike Welcome To the Canteen, this concert album was jazzier and more fluid with Chris Wood's sax and flute up front more often. In addition to such musical sophistication, every song was an extended jam with marvelous percussion and a greater than usual dose of stinging electric guitar from Winwood in addition to the splendid keyboard work. The recording was from the tour that followed Shoot Out at the Fantasy Factory and featured the Muscle Shoals rhythm section of David Hood on bass and Richard Hawkins on drums, a couple of lauded session players from Alabama who knew how to groove. Most Traffic fans seem to rate this album as mediocre, but it was an important cog in my musical education and remains high on my list of favorites.

I began my sophomore year with a new purchase-the Mr. Fantasy album from 1967. This was Traffic's debut album, and considerably different in tone and texture from the early '70s stuff I had been digesting regularly, but I spent many hours spinning that album. Unlike most of the others, this one never seemed to catch on with my friends at all, but I loved Mr. Fantasy. Every track-except a couple of offerings from occasional member Dave Mason-played directly to what I was experiencing on the inside. The fact that Steve Winwood was approximately the same age when he recorded the album as I was when I was listening to it probably had some effect, too. I was convinced that it was as colorfully brilliant as any of the breakthrough albums of that psychedelic period.

III

And so I continued to bounce along in quiet worship of my musical hero and his assorted band mates, and gradually I picked up the complete Traffic catalog as well as other albums on which Winwood played. He had become a part of my own artistic development in a deeply personal way. As I studied the various fine arts disciplines presented in the classrooms of Maryville, I carried a growing awareness that the initial impression received from art was just an invitation to delve into the subtleties. A significant portion of this aesthetic maturation had been influenced and nurtured by hours of digesting the songs and performance of Steve Winwood. Already painfully introspective, many of my own writings began to demonstrate an abstract cohesion and an intentional lack of conclusiveness-I was writing Traffic-styled jams, although the occasional appearance of this voice in my academic papers resulted in chastisement from my professors.

With very few exceptions, the only people among my peers who knew about Winwood's prowess had learned of such through their acquaintance with me. But then that all changed. "While You See A Chance" hit the airwaves in 1980, and my possessiveness was gone forever. Steve Winwood became a legitimate top-40 star. Although I was a little unsure what to think of the heavy use of synthesizers, I liked the new album, and I was quick to proudly point out that every instrument on the record was played by Mr. Winwood. The songs were good, in some places brilliant, and I felt some sense of validation at his newfound universal recognition.

My life soon got busier and I found less and less time to devote to records and turntables, but I still managed to keep some of the music playing. My first year out of college was enhanced by the follow-up to Arc of a Diver, another entirely solo-performance called Talking Back to the Night. The album didn't do as well commercially, but I played it endlessly and let it bounce through my heart as well as my brain. I had married at twenty-one, and when Talking Back to the Night was released we were expecting a baby. I actually suggested to my wife that we name our child "Valerie"-the title of one of the catchier tunes. She quickly and adamantly rejected the suggestion, but the request fits neatly in my cache of Winwood lore.

The middle and latter part of the 1980s, with MTV and rap dominating the new music scene, held little in the way of musical satisfaction for me, but I was content with my albums at home and my homemade cassettes of those albums in the car. Winwood remained a top 40 star with several commercial successes, and "Higher Love" and "Roll with It" both went to #1 on the Billboard chart. He even won Grammies for Record of the Year and Best Male Vocal Performance in 1987. Many of his old fans were horrified and accused him of "selling out," but I didn't hold it against him. After all, he deserved his time in the pop spotlight, and the music he was making, while not the sharp-edged inventiveness of Traffic nor the soulful blues of the Spencer Davis Group, was still a damn sight better than most of the other tunes on the radio airwaves. I bought Back in the High Life and Roll with It, just as I would buy Refugees of the Heart in 1990 and Junction 7 in 1997. Each album has brilliant moments, but when I was in the mood for Winwood music I still reached back to the earlier stuff. I went through several Winwood periods, dwelling particularly long in Traffic's John Barleycorn Must Die and Blind Faith's self-titled gem, the remarkable album he made with Eric Clapton, Ginger Baker, and Rick Grech in 1969.

Although not directly related to the music, the most impressive moment for the 80s Winwood was when he married Eugenia Crafton, with whom I had attended Sewanee Academy in 1975-76 and where, being both beautiful and utterly personable, she had been the object of considerable lust within my 15-year-old heart. One day she and a friend of hers were standing nearby and some sort of greeting was exchanged between us. The radiant Genia smiled and said to her friend, clearly meant for me to hear, "he's cute." I knew even then that the comment, while intended as a compliment, was said in the manner one discusses a puppy or perhaps a baby in a carriage, but it made my head soar nonetheless. ("Dear Mister Fantasy, play us a tune . . .") If only I had managed to utter a suave reply, instead of blushing and stumbling away, my life might have taken a dramatic turn-Steve Winwood might today be stepfather to my children.

IV

During the 1990s my musical tastes continued to expand into new realms and genres, but Winwood was always in there somewhere. One night I turned on the television to see him and Jim Capaldi playing at the Bluebird Cafe in Nashville. There was no audience except the camera. Most of the tunes were with Winwood on an acoustic piano while Capaldi thumped on congas or fiddled with some other percussion instrument. It was great little show, and it turned out to be a prelude to a new Traffic album and tour. Chris Wood had died in 1983, and the two surviving members of the Traffic nucleus, uneasy about using the Traffic name for something that didn't include their friend, chose to play all the music for the album themselves and dedicate the project to Wood. The music was great, and the spirituality of Winwood's Refugees of the Heart-a greatly under-appreciated album-was carried forward on Traffic's Far From Home beautifully.

As I approached 40 I felt that my perspective was actually catching up with Winwood's, and I realized that his career milestones had become artistic landmarks for my own life. At first the timeline is skewed since I discovered his music sometimes ten years after the original recording dates, but the music always fit perfectly as the soundtrack for whatever point in time I crawled inside a particular album. When he deviated from his own artistic path for a few years, I took the opportunity to more fully dig into his earlier work and in that process I developed a sense of his changing character as an artist as well as my own. And just as I was breaking through to the very reality that dramatic changes are necessary in my life, Winwood steered into a spiritual vein that played perfectly in tune with my own events, thus providing a musical mirror into which I can either stare or glance beyond the fantasy self of rock n roll and see the flesh-and-blood spiritual self.

EPILOGUE: The Concert

The passing days were too numerous to follow, and life events blurred together in one unsteady memory as middle-age hung on my mind like a forgotten ham in a long-abandoned barn. And then came About Time, Winwood's 2003 CD offering. Just a few seconds into the opening track, "Different Light," the Hammond organ jumped out and shook me to my rusty core. I picked up the phone and started calling people and letting them know that the most important album to be released in 30 years was now in the stores. I meant it, too, although I knew my raves would fall largely on disinterested ears. My own exuberance was buoyed by the news that Steve Winwood would be appearing in concert at the Florida Theatre in Jacksonville, Wednesday, April 28, 2004, a wonderfully quaint venue that would be well-suited for the minimalist band with which he was touring.

My daughter Christi, who had been force-fed Winwood music since she was in the womb and was not named Valerie, attended the concert with me. Having grown into an independent-minded 19-year-old, she possessed a keen intellect and an astute ear for music. My hope was that she would take from the evening at least some assurance that my love for this particular artist was not a mere adolescent rock n roll obsession but an aesthetic appreciation of considerable depth and merit. That's a lot to ask of anyone, of course. Fortunately she does have some respect for my musical tastes (I think) and brought a willing and open mind along to the show. But beyond the musical experience, taking her to the concert was like introducing her to a relative or lifelong friend-she would have the opportunity to glimpse some of my own organic past in the form of the artistic energy which would be loosed during the evening.

The concert itself was as fine of a performance as I could have expected. The theatre was packed with aging rock n rollers mumbling excitedly about their favorite song or how they've been a fan since Winwood was a baby. The songlist was a retrospective that included nuggets from Traffic, Blind Faith, and the Spencer Davis Group. I couldn't help providing a running commentary throughout, although I tried to keep my chatter to a minimum. Winwood sat at the Hammond B3 for most of the evening, but he picked up his electric guitar for "Dear Mr. Fantasy." The only musicians on stage for this number were Walfredo Reyes Jr. behind the drum kit and Randall Bramblett, who set his flute and sax aside to take the seat behind the organ, just as Chris Wood would have done in concerts past.

As they moved into the groove at the beginning of the song, with Winwood standing out front singing into the mike, the sea of bald heads with grey ponytails around us nodded in silent approval. When Winwood stepped into the solo, he turned to face the drummer, and all three instruments locked together in a building frenzy until the guitar leapt beyond the song and soared around the auditorium, through the ceiling, and out into the starlit sky before gently returning to the stage in a perfectly timed instant as the band slid back into the melody. After about 15 seconds, the gasping middle-aged thumpers found their breath and a rousing standing ovation drowned out the final minute of the song. Then Winwood set the guitar down and casually ambled back to the organ, a modest smile on his face.

My veins were buzzing for weeks. I kept calling Christi and saying, "Wasn't it great? Wasn't it great?" She acknowledged that it was a good show and that Mr. Winwood is a remarkable musician and indeed a special artist, but she isn't ready to discount the idea that he is also an adolescent obsession permanently lodged in my slightly decayed brain-a fair enough assertion, I must concede. But I can imagine the day when she tells her children about the night when music welded the past and present together in a magnificent package that rhythmically shook the heavens, putting a smile on her daddy's face and aptly demonstrating the limitations of his words.

Authors | Home | Top

"I see myself as a mainstream American writer. This book is about class," Brewster Milton Robertson said during a Q & A session at a recent writers' conference in Florida. Robertson was commenting on his writing career and his new novel, A Posturing of Fools (River City Publishing, Montgomery, AL, 2004).

Indeed, much in this novel would appeal to mainstream readers: an elegant setting (the renowned Greenbrier resort); a likable, picaresque protagonist (Logan Baird); a shrewish wife (Rose), reminiscent of Shakespeare's Kate; libidinous females who use Logan Baird and are used by him; a male erection drug (Virecta); corporate hype and snobs galore. Just about everyone in this story is a fool, and Logan is a self-admitted snob. Yet, somewhat redeemably, he knows it, regrets it, and tries to make the best of a shaky marriage and get closer to his beloved son Paul. At the end of the story, Logan prepares to take a dream job in New York City as conditions arise that may cause him to backslide again.

A Posturing of Fools , then, is more about false class than true. True class appears in the novelist John Paul, Logan's close friend who dies and leaves Logan a career-changing gift; in Logan's few writings; and in his realization that he's a country boy at heart. This awareness comes as an epiphany near the end of the novel when, driving back from the Greenbrier, Logan stops and walks across a stretch of Virginia countryside:

Excerpt from A Posturing of Fools

Brewster Milton Robertson

The day was absolutely perfect.

I took my time driving back over the crooked mountain roads.

After I'd passed through Newcastle, the harsh light of the afternoon sun in the countryside brought back memories of my boyhood on the farm. I stopped beside a long, gently sloping hillside that had recently produced a crop of corn.

I got out of my car, removed my tie, and tossed my jacket across the seat before I closed the door. Then, bemused, or perhaps bewitched, I jumped the roadside ditch and scrambled up the weedy bank to the fence.

Some things-like riding a bicycle, they say- are never forgotten. Climbing expertly through barbed wire fences is, for a former farm boy, a trick that is undoubtedly imprinted on the genes.

Moving gingerly, I emerged undamaged on the other side of the treacherous wire.

Stretching before me, the spiked stubs of the newly harvested cornstalks stood like toy soldiers in neat rows rising up the slope. As my eyes moved upward, I could see where, three quarters of the way to the summit, the cultivated field gave way to a narrow tangle of wild blackberry brambles. A few yards beyond, there was the beginning of a towering forest that crowned the hill.

Overhead, except for a line of thunderheads on the rim of the distant horizon, the sky was virtually cloudless. A lone hawk was a tiny speck, drifting in effortless circles against the sunfaded, almost colorless sky.

Moving closer, I could hear the soughing of the breeze stirring the treetops. Far off, a half-imagined rumble of thunder whispered echoes of my long-lost innocence.

Those woods beckoned me.

I began climbing.

I was transported back in time. The summer I was twelve, with my younger brother, Jim, and a neighbor's son, Carl-who was several years older and came daily with a phlegmatic dappled-gray plow horse named Nell-together we'd made a crop of corn on an eight-acre piece of rocky Virginia hillside, which looked a lot like the one I was climbing now.

That summer's inglorious labor had been an altogether uninspiring fate for a suppressed romantic male. Each morning I'd awoken to the endless prospect of undistinguished days. Beginning at the top of the dusty hillside, we'd plowed and hoed our way, cornstalk by cornstalk, down the dusty, rock-strewn slope. Laboring under the relentless sun for most of the summer, the three of us had worked like automatons, struggling vainly to keep the indomitable scourge of morning glory vines and farmer's wiregrass away from their mindless lusting to ententacle the cornstalks in a death embrace.

To my pubescent melodramatic mind, our labors had called up images of Dante's Inferno.

Rats on a treadmill, top to bottom, each cycle had taken perhaps two weeks. Each time we reached the bottom row, there was no celebration. We had simply turned and marched, numb and resentful, back to the top to begin again.

Then, one hot day-just as unceremoniously as our labor had begun-without fanfare, it was over.

My brother and I had shouldered our hoes and watched Carl unhitch old Nell. In a few days, the grownups had come, harvested the scraggly crop, and hauled it off.

That summer's labor had felt totally unredeeming. Even the morning glories and wiregrass appeared driven only by pure meanness. The land was totally unsuitable for growing anything but weeds. Once the crop was harvested, even the weeds had appeared to lose interest and languish. And, in the end, the corn was destined to be fed to the livestock anyway-a rather pointless objective to my pragmatic way of thinking, since it would be my brother and me who eventually had to spend the winter carting the sorry corn and fodder to the chickens and cows and hogs.

At the close of that summer, I had put away forever most of what was my childhood. A few weeks later I would begin riding the school bus five miles into town to enter the big consolidated county high school in Melas where I would demonstrate my skills in kicking and throwing balls of every shape and size.

And discover girls.

Now I climbed awkwardly in my polished Italian loafers. When I reached the topmost rows, I found a clutter of lunch bags and candy wrappers mixed with soft drink bottles and cans at the edge of the maze of blackberry brambles. Two rusting tins labeled "Pork and Beans"-and several smaller ones that had contained potted meat and Vienna sausages-had been carelessly tossed aside to lie rusting in the sun. This rude litter was a reminder that crops of corn do not make themselves. I walked along the border of the blackberry thicket to where I could see the almost invisible trace of a narrow beaten-down track leading through the tangle to the deeper shadows at the edge of the trees.

Feeling a tad foolish, a professional man headed for his destiny in New York and not at all dressed for this adventure, I picked my way carefully along the clutches of the bramble-strewn pathway toward the trees. When I finally threaded my way into the leafy overhang of branches, I looked back down the hill. My car looked like an abandoned toy.

A freshening breeze mixed a heavy scent of honeysuckle with cooler breaths of the approaching storm.

I felt strangely astraddle a chasm in time.

My memorable twelfth year had been a confusing time for me. For reasons I didn't understand then, I had been skipped ahead in school. I was large for my age and, unlike the sons of our farmer neighbors, I usually left the swimming hole early and put in a lot of serious practice at passing and kicking a football. And, that seminal summer, I suffered a plethora of euphoric hormonal influences. My voice played tricks on me, and I began sprouting dark hairs in all those funny places. In the evenings, I found myself reading less of Robin Hood and Captain Nemo. Already, I'd been caught sneaking copies of Tropic of Cancer and Lady Chatterley's Lover out of my aunt's library.

After dark, on the pretense of playing Old Dead Mule with the neighborhood gang, I discovered the perfect excuse to spend a lot of time hanging around the teenage girl across the river.

She thought I was fourteen. And I was content to let her go on believing this cheeky invention. One night, crossing the moonlit surface of the torpid river in a leaky old rowboat, she brushed her mouth against my cheek and whispered that I was beautiful-hungrily, she'd tasted me.

After that, I was never the same.

But I had still daydreamed about being a pearl diver on a South Sea island or a movie star or a dashing jet pilot, and I sometimes slipped off alone to play out these romantic fantasies in the woods at the top of our sorry cornfield. There, shadowed by the fear of discovery, I would self-consciously don a homemade loin cloth, cut the thick grapevines at their roots, and go swinging through the trees, playing a solitary game of Tarzan.

As I took in the sweeping vista out across the sunlit country landscape, the memory of that summer was seductive.

I took another look at my car and stepped through the leafy drapery. It was as if a curtain had closed behind me, shutting away the lively chorus of birdcalls and insect sounds.

Enthralled, I picked my way to a giant grapevine hanging from a towering oak and tested it tentatively with my full weight. That ropey vine would swing a long way out over the slope of the clearing. A good ride for an adventuresome lad; the idea captured my imagination.

Emitting a peculiar green luminescence filtering down through the leaves, any forest encompasses a universe all its own. The timeless, fairy-like setting of leaf-strewn mossy carpets, towering trees, huge vines, and lacy ferns is unforgettable.

The first time I'd seduced Rose, we'd been at a cabin party just on the other side of this very mountain. That drizzly afternoon deep in the dripping woods back of the cabin, we'd found a gigantic boulder, perhaps ten feet high and flat on top. Covered by a big plastic raincoat, stark naked in the fine silver mist, we'd shut out the world.

I was fifteen.

There would never be another time like that for me....

After a time, I threaded my way back through the trees and brambles. I looked out over the broad valley. High above a barn and farmhouse, a red kite was floating in the wind--flying free, as high as the hill. I traced the line to a small boy and a man. They were tiny figures in a homespun tapestry. The man's hands helped the boy hold the cord. Together they intently watched the kite dance on the breeze.

After a moment, I reluctantly made my way back down the hill and drove away, wondering if there would be woods with grapevines and places for flying kites in the suburbs of New York City.

Authors | Home | Top

Note: Occasionally, Writecorner Press likes to venture out of field and give readers other media to explore. In the following article, Karl Schwartz highlights his career as a sculptor and painter in New York City and intersperses some of his favorite works. Now living in Gainesville, Florida, Schwartz works every day and continues to produce art that is innovative and engaging.

SomeWe get exmples We Works inWSSom

Works in Expressionism Expressionism

Karl Schwartz

At the age of five, I painted Washington Crossing the Delaware on the kindergarten blackboard. From age seven to nine, I copied Norman Rockwell’s illustrations in the Saturday Evening Post and illustrations in Collier’s Magazine.

By 17, I was an apprentice in a New York advertising art studio delivering layouts and paste-ups to the big advertising agencies Cecil and Presbury and Kenyon and Eckhardt on Park Avenue. While working at the art studio, I attended Pratt Institute at night. There I sketched from nude models and studied design and composition. It was then that I discovered the many ways that one could work wire. For a homework project, I did a collage using a small piece of wire among other scraps. After I fashioned several three dimensional pieces, I met the window display consultant at Bloomingdales who referred me to my first agent.

GODDESS

Sculpture - 6 ft.

Brass Wire, Hardware Mesh, and Sheets of Gelatin

By 21, I had my own studio. I worked day and night, turning out wire pieces for stores across the country, especially angels for the Christmas Season. When my agent introduced me to Tom Lee, the interior designer who designed the wire Christmas Angels for Rockefeller Plaza,* he immediately began to use my work. He said, “Karl, you have magnificent flair and a new way of looking at things.” I worked with Tom Lee for 20 years until he was killed in an automobile crash.

Five years ago, I did 100 wire angels for Saks and also completed commissions for Tiffany and Co. and Van Cleef and Arpels.

Several times, my work has been used by Bergdorf Goodman. It appeared in Graphis Display, a photo essay of the best window art of the last 25 years published in Zurich. A reference from a president of Saks Fifth Avenue, for whom I had done several pieces, won me a commission to do six life-size wire mannequins for the opening of the Valentino Boutique in Paris.

CONSTELLATION

Mixed Media Wall Piece

Painted Canvas, Steel Wire, Steel Ribbon

26 in. x 23 in. x 4 in.

I have related or combined painting and sculpture in constructions of mixed media. I stretch canvas across free-form wire forms, painting the canvas in abstract design, while adding wire and ribbons of metal. My dealer and gallery are interested in this kind of work, and the Museum of Modern Art wrote that they would attend a show in New York City.

I like to do “automatic” paintings. Rarely ever do I use sketches or studies. I dive right into the media and develop the work along the way. My influences are the works of Willem de Kooning and the abstract expressionist Franz Kline’s black and white paintings.

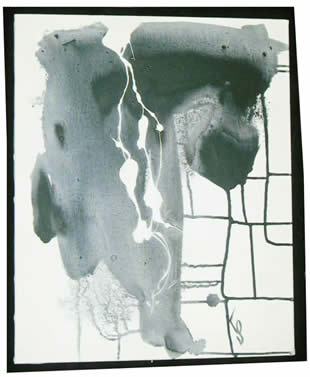

SHOCK I

Acrylic on Stretched Canvas

16" x 20"

My abstract expressionist work expresses subconscious behavior and mood.

SPLASH

Acrylic on Stretched Canvas

16" x 20"

I don't like symmetry. Nature is not symmetrical. A-symmetrical approaches enable me to experiment with design and composition.

CONFLICT

Acrylic and Aluminum on Canvas

16 in. x 20in.

FESTA

Acrylic on Canvas

16 in. x 20 in.

I have enjoyed seeing my work in the windows of Fifth Avenue in New York where more people see it than in a gallery. It is especially satisfying to have write-ups about my work in Women’s Wear Daily, The New York Post, Dance Magazine, Travel and Leisure, Interior Design Magazine as well as publications abroad. My works have been purchased by collectors in the USA, Paris, and the Middle East.

PAS DE DEUX

Sheet steel, steel wire

33"

* Tom Lee's Christmas Angels have adorned Rockefeller Plaza for over 40 years.

Authors | Home | Top

Peter Sears is a graduate of Yale University and the Iowa Writers Workshop. He won the 1999 Peregrine Smith Poetry Competition with The Brink (Gibbs-Smith Publisher). The book then won the 2000 Western States Book Award in Poetry and in 2009 was named one of Oregon’s best books by the Oregon State Library. His poems have appeared in The New York Times, The Atlantic, Rolling Stone, Orion, The Christian Science Monitor, Mademoiselle, The Oregonian, and Mother Jones and in literary journals such as Field, Antioch Review, Iowa Review, Black Warrior Review, Xanadu, University of Windsor Review, Cimarron Review, Beloit Poetry Journal, Ploughshares, Northwest Review, Seneca Review, and other influential publications. His writings include Tour, his first collection of poems (Breitenbush Books); two supplementary teaching texts, Secret Writing from Teachers & Writers Collaborative and Gonna Bake Me a Rainbow Poem from Scholastic Inc; five chapbooks; and Green Diver, published in 2009 but consisting of poems published earlier and since revised. Other Sears achievements include founder of the Oregon Literary Coalition, a statewide advocacy organization; cofounder. with Kim Stafford, of Friends of William Stafford; cofounder, with Michael Malan, of Cloudbank Books; and recipient of the Stewart H. Holbrook Award for contribution to Oregon literary life. At Bard College Sears served as Dean of Students, and at Reed College he taught creative writing. He is presently on the faculty of the Pacific University MFA Writing Program in Forest Grove, Oregon. He lives in Corvallis, Oregon.

Update: Peter Sears was recently named the state of Oregon's Poet Laureate. The award is for two years, and Sears will be traveling throughout Oregon to promote poetry and encourage emerging and established writers. In 2012 Writecorner Press sponsored Sears' visit to Gainesville, Florida, during which he read selected poems to a standing-room audience at Oak Hammock at the University of Florida. For Writecorner's review of Sears' poetry, click on Fiction Nonfiction Poetry under Reviews, left sidebar of our home page.

The first three poems below are from his chapbook Luge (2008). These are followed by three poems first published by Writecorner Press in 2012. "Oceans of Kansas," the last Sears poem below, first appeared in The Oregonian, the primary newspaper of Portland. "Spec 4 Sly Gifford," a Sears short story published by Writecorner Press in 2013, follows the poems.

The Rain Sounds Like a Delicate Eating

You wake to rain, roll over, and let the softness fall

out of the bottom of your brain.

You wake again, later, to rain, and slog into the day,

out the front door, down on to

the flagstone path by the ivy and Doug firs dripping.

Can you hear a drop strike a leaf of the ivy?

Yes, you think you can.

You see a leaf flutter.

You look from one struck leaf to another, and another.

The moments between drops

are like lighter leaves under darker leaves.

You listen to what you call "front rain" and "back rain."

Front rain is what you hear,

back rain is what you think you hear, what you want to hear.

The rain on the ivy, you say to yourself, is like a clicking,

like a delicate eating.

Standing water you like too,

and hearing rain strike standing water.

Rain may carry back to your something you had forgotten

or hadn't thought of in a while,

particularly soft rain.

What of rain that blows out of trees,

down the back of the neck,

making you laugh and wrinkle your neck?

And yet you say you really don't like rain. It's too beguiling,

you don't believe it. What do you mean

you don't believe it?

I believe that when I hear a poem,

I hear the silences between the words.

Like rain. I hear the intervals

between rain striking leaves or standing water.

Maybe My Head Is an Airport

As a kid I loved the fighter planes of World War II.

Loved them so much I felt I was a fighter plane

and if I got shot down and crashed and burned up,

it wasn't clear if I could shift back to being just

a third grader--or if I'd gone, shivering in

a cloud that wasn't coming back. My worst fear

was returning from a mission, short on fuel,

all shot up, and our aircraft carrier, right down

beneath me, is sinking. Maybe I was playing too

much war and should have been made to work

longer on the vegetables in the Victory Garden

and eat lima beans that tasted like cardboard.

I didn't know then I could worry better about

the war by working in the Victory Garden.

I didn't know it was fun to pull my wagon from

house to house, collect old newspapers from

people's garages, and take them to school

for the war drive. The janitor weighed them,

gave me a slip of paper with my name, date,

and the weight, then piled the newspapers

way up, with a forklift, way up over my head.

Dream of Following

I am following my father and mother,

following them although I don't much like

the idea, and I don't much like

that the distance to them grows smaller,

so small I'm catching up to them. You'd think

we'd have much to say to one another.

We don't. My father motions me

to look back over my shoulder.

There's my daughter following me.

That's mean of him. I want to hail her,

tell her to slow down.

But I don't. I turn back, they're gone.

Three Poems by Peter Sears (2012)

Morning Light

I'm here on the deck, blowing on my coffee,

watching poppies open slowly in the morning light,

one orange cup after another. They help me forget

that my stomach floats in my throat, here in week three,

round two, of my chemo. I have to remember to eat

and that, in my mind, I am not always all here. I stand

--I've learned about the dizzies--and imagine myself

strolling down a flagstone path which I'll build next spring

after the rains. I look forward to the quick spring light

glinting off the flagstone that I will lay one stone at a time,

on my knees, on an old cushion, with a deep stack

of stones to choose from. This stack I will call

my little ziggurat. I sip my coffee. The morning light

is still too heavy to lift over the hills into our backyard.

Yet the poppies continue to open their orange cups,

one after another, around their black stamens.

My coffee, I'll sip it, then take a full, luscious swallow.

Back from War

It's nice to have our son home again.

We worried every day, especially when we didn't hear.

He's back now from Afghanistan

with a pretty bad concussion,

but he has his music, games, and computer upstairs.

It's nice to have our son home again.

You may have seen him in his fatigues downtown.

He was good about looking for work

when he first came back from Afghanistan,

but his concussions were too bad. He was begging

the other day--said he was just going out to get some air.

Still, it's nice to have our son home again.

He's sure on a lot of medications.

We hope the VA will soon say he's getting better.

At least our son is back from Afghanistan.

Please, if you see him downtown begging,

point out the bus and write down the right number,

and tell him it's nice to have him home again,

that you're glad, we're all glad, he's back from Afghanistan.

I Don't Know

That's what I'm saying: I don't know. I had come down

to the bottom of the stairs and was about to join

the others when I thought I had forgotten something,

and turned. There he was, or it was, standing

three or four steps down from the upper landing,

his shoulder line even with the top of the stairs.

Had I surprised him? Or it? That's how it seemed, and

that he didn't want to remain there with the sun

flowing through him. Then, I don't know, he wasn't there.

I breathed way in and went out to join the others

in the kitchen. I liked the light rain and went out on

the terrace. Had I seen something? It wasn't clear.

I remember only turning fast and that I hadn't planned

to turn at all; and then I looked up, up the stairs.

Oceans of Kansas

Daughter, remember how you love Kansas, because of Dorothy,

and I told you that millions of years ago

Kansas was underwater--

the whole state an ocean full of fish and seaweed,

and you cried crazy? I said, Kansas is fine now.

Days later you were still drawing pictures of houses underwater

and long hoses down to the houses

and machines on the side of the houses to pump the air in

and people with helmets on with little hoses

and fish swimming into the house

and sneaking into the refrigerator and out

before you could shut the big white refrigerator door.

I show you how to draw a refrigerator with the door open

and fish swimming in and out at funny angles.

You keep crying a little as if you have forgotten why,

and turn your head away

and draw and draw.

You say we have to keep drawing

if we are going to stay alive underwater in Kansas.

Spec 4 Sly Gifford

Peter Sears

Specialist 4th Class Sly Gifford* had a problem with the mail drop sliding into the ocean. Three weeks in a row the pilot had been unable to drop the mail in the designated area. Keeping things running smoothly was Spec 4 Sly Gifford's responsibility there on "The Mound," a signal site in the Aleutian Islands, not listed among U.S. sites because it monitored Russian voice traffic. With the Mound not officially existing, neither did the voice-operated soldiers, who called themselves "Noodles." The noodles claimed their non-existence was sufficient reason not to wear uniforms on duty. The Colonel did not press this negligence because he didn't want to have to go to the Mound to inspect. The soldiers referred to him as "Happy Hound." Among the noodles he had a few informants, who were, for the most part alcoholics. Through them he brought up for court martial a fellow who allegedly referred to him as Happy Hound and bounded about the bar there on The Mound, giggling and twiddling his ears. The case didn't materialize, however, because the prosecution's witness wilted under oath, unwilling to confirm the claim of misconduct.

The noodle's character witness had been Spec 4 Sly Gifford, who had volunteered. He received much credit from the noodles for getting the fellow off, even though he had done no more than say, under oath, that he had known the fellow for a couple of years and found him upstanding, reliable, and empathetic. The Colonel did not like it that Spec 4 Sly Gifford had volunteered to be the character witness, but, as he reminded the Colonel, there could be not trial without a character witness. Fortunately, the Colonel did not know that Spec 4 Sly Gifford was the one who, earlier, undermined his campaign to get the men to call themselves, "The Prisms." The Colonel had T-shirts made up beforehand and was planning to visit the Mound to present them and give an inspiring speech, only to learn that the men had chosen "The Noodles" as their name. The Colonel refused to have the T-shirts made up with "The Noodles" on them and he refused to show up at the ceremony. This fiasco did not sit well with the Colonel, and it was Spec 4 Sly Gifford whom the Colonel had told to make sure that the naming campaign was a resounding success. Incensed by the failure, the Colonel told Spec 4 Sly Gifford that this noodle business had been one of his "major failures" and that his gratis position as "coordinator" of the Mound was in serious jeopardy. Spec 4 Sly Gifford was not shaken, however, because the incident would not appear on his record because it would reflect badly on the Colonel. Nor would the fact that Spec 4 Sly Gifford had gotten to the prosecutor's primary witness beforehand and warned him of consequences should he help railroad his poor fellow noodle. During this conversation, he mentioned the temperature of the ocean off the island and the height of the waves as they crash against the rocks.

But all that was insignificant compared to what Spec 4 Sly Gifford now faced. The noodles told him that they were going to shoot down the mail plane if the pilot couldn't drop the mail in the designated space, a large compound next to the bar, a compound from which the mail could not slide off into the ocean. Spec 4 Sly Gifford had reminded the noodles that the pilot was new and, naturally, nervous. Spec 4 Sly Gifford was reminded, that beyond food and drink, the only other major item was mail; furthermore, that to see the mail float down and away and bounce and roll into the ocean is enough to craze a man. So the noodles had mounted a machine gun in the bar and would bring the mail plane down, they said, if the mail drop missed again.

The pilot had missed because he was incompetent. He did not fly such planes. He was lucky not to have crashed into the bar. He was a goon of the Colonel's. The noodles figured the Colonel had appointed this pilot to avenge some sort of humiliation at the hands of the noodles. So they had no problem with the plan of brutal retaliation. However, shooting down a mail plane could end the entire operation at The Mound. Surely they realized this. Well, then, why not try to bring back the previous pilot, who was magnificent, who never missed the mail target, who flew in when told it was too windy? Oh, were it only that easy. The previous pilot lived in the little community on the mainland. His name was Fred. Fred wanted to be called "True Sled," but the name didn't stick. He had been flying the mail run for several years. His wife, Martha, was also called "Nighthawk," but not very often because she didn't like it. "Nighthawk," she claimed, scared their two children.

Fred and Martha and all the others in the community detested the Colonel for holding up programs and funds directed by the feds to go to the community. At a town meeting, Martha and Fred took it upon themselves to go after the Colonel, to undermine him, to bring him down.

Martha told the Colonel that she thought he should wear his dress uniform more often around town because it was so handsome. When he was around, she got all blinky. Soon she and the Colonel were having an affair. Fred, in charge of gathering evidence, installed visual monitors in the Colonel's bedroom; these recorded vivid coverage of the romping erotica. When Spec 4 Sly Gifford, a good friend of Fred's, pleaded with him to come back and fly the mail deliveries, Fred begged off, saying that he had to focus on the campaign as he called it. Besides, surely the Colonel would not let him come back because it had been the Colonel who dismissed Fred, and Fred, as Martha's husband, was his rival to Martha's love and loyalty. Fred added that he was getting some splendid footage of the Colonel dressing up as a polar bear and gallivanting around the bedroom.

Spec 4 Sly Gifford told Fred that whatever evidence came out of Fred and Martha's community would probably be intercepted by the Colonel's goons at headquarters; thus, damaging evidence had to come from a different source. This is when Spec 4 Sly Gifford had what he thought was an epiphany: the material would be sent by the Russians, namely those Russians at the comparable site across the Bering Sea to the noodles at the Mound. This site the Mound monitored for voice transmissions and vice versa. The exchange, known to both, Spec 4 Gifford added, would not be the cause of escalating tension, but, on the contrary, a source of stability, for each power, the US and the USSR, would come to know, on a regular basis, something of the other and, with that, could remain assured of a balance of power.

Spec 4 Sly Gifford offered Fred a second point, that the present pilot was so bad he might crash the plane anyway, without any assistance, and kill himself, and that would force the Colonel to replace him. This, Fred countered, would take too long, even if it did happen, and, as for the idea of bringing in the Russians, that would mean breaking a basic law of the Mound: no contact with the enemy unless directed by the Colonel. Spec 4 Sly Gifford wondered if he could chance breaking this rule for a questionable scheme in the first place. There were other questions. Was there really any reason to believe that Fred would fly the mail plane again? The new pilot had been in place now for three weeks. The next mail delivery was due in five days. Spec 4 Sly Gifford tried to grasp the primary question: If the Colonel went down, would he take Spec 4 Sly Gifford with him? Spec 4 Sly Gifford saw in his mind's eye that machine gun mounted in the bar. Could he prevail upon the noodles not to try to shoot the mail plane down if the drop was yet another failure and all the mail was lost? He doubted he could. He wondered if it was even a good idea to try, that just bringing it up would incense the noodles even more. Could he sabotage the machine gun? If the noodles caught him doing that, what would they do to him, these wonderful comrades for whom he had kept things going smoothly despite the Colonel's relentless aggravation?

Spec 4 Sly Gifford admitted to himself that he was in over his head. To force himself to confront this reality, he said out loud, "I am in over my head," and that reminded him of the swimming test at camp in New Hampshire when he was 10, when he had, for weeks, faked it and walked along the bottom. The test would be held in open water, water in which he would be in "over his head." He couldn't swim. But would he own up to his deceit--he had always been good at deceit--or actually try to swim the distance? He couldn't swim the distance. At least he thought couldn't. But he had to. So he dog paddled and then sank and then dog paddled back up to the surface, dog paddled a little further, then sank again, dog paddled again to the surface, and so on. He thus passed but was told his swim was the worst display of swimming at the camp. The other campers thought what he did was great, that he was courageous and foolhardy at the same time. No higher compliment could they pay.

Guys who didn't know him wanted to be his friends. They asked, "What was it like to sink and try to dog paddle back to the surface? Could he dog paddle his way out of this dilemma? Just think, only a few days ago, he thought about re-enlisting: the money, the easy work, the routine, the free meals, everything taken care of, and the noodles, what great guys, and, of course, their appreciation of how he goes to bat for them and gets things done, despite the Colonel's efforts to the contrary. That was before Joanna, before she wrote to him and said she was waiting for him. He thought about her a lot. He could see her in his mind. He counted the days. With two months left, he was a short-timer. He had to get out of this mess and receive his discharge from the Army.

But he was boxed in. He admitted it. He had never really been boxed in and with such serious conditions. If the jig was up, one way or the other he might land in the brig, and then he would be cut off, incommunicado. He couldn't tell Joanna why his letters had to be so bland, why hers were read over several times. Perhaps it was for the better that she didn't know he was in the brig. Then would he, Spec 4 Sly Gifford, slide from her thoughts just a little too far to make a comeback? And what of his military record? How much would it be damaged by his participation in this effort to get rid of the new mail plane pilot? Maybe he would be shipped back to the states to a military prison. If not, maybe it would hurt him in trying to get work back in civilian life. Maybe he really should consider re-enlisting. He could do a second three-year hitch. No, he would not do that. No, never. He would beat this, one way of the other. So he went back through the entire situation slowly.

The first question was whether the noodles would fire upon the mail plane and bring it down if indeed the drop proved again to be a failure. He figured that they would get all lathered up with beer and fire the machine gun, but not necessarily at the plane. Just fire it, to show off. But not try to hit the plane because they might bring it down and then there would be all hell to pay. If Spec 4 Sly Gifford was right in his reading of the noodles, he would have time to try to re-negotiate the standoff. If he couldn't, the Colonel would be in a position to court martial the entire bunch of noodles.

An hour later he came upon another idea: while this new pilot had the Colonel's permission to fly the mail plane, he might actually not want to, given how little he knew about flying. So he might welcome word from the flight desk that, somehow, the paper work had gotten scrambled and he could not take the plane up, not just yet. The paper work would have to be re-filed. What Spec 4 Gifford liked about this strategy was that he had plenty of friends in the flight office who would love to engineer it. Of course the mail would not be delivered and would pile up there in the hangar. That could become a problem, but nothing compared to the threat of another mail miss, the mail falling into the ocean, and, who knows, perhaps the loss of the plane and its pilot.

Should this ploy at the flight office work and the flight be shelved, the Colonel would be incensed, but one of the staff could explain to him how fine it was that a possible disaster had been averted, and he might get the idea that he could correct the matter, pull back from the brink. Likewise, Spec 4 Sly Gifford would get word to the noodles what he had done and why, and they would probably regard his effort as cunning and helpful to them, assuming, of course, that they would eventually get their mail. Spec 4 Sly Gifford was sensitive to the bottom line, right along with them, because his mail went first to the Mound, and Joanna had written, before the change-over of pilots, that she would be sending on a group of photographs of herself. In his imagination, Spec 4 Sly Gifford saw a letter of hers with photos sliding into the ocean each time the new pilot had missed. He so wanted to seek revenge against the new pilot, but he knew that the true target should be the Colonel. He would try to develop a plan to take the Colonel down and not let the Colonel take him down with him. He saw this as the most important challenge of his life.

* Editor's note: While this fun-filled story is set during the Cold War between the U. S. and the former Soviet Union, its fiction suggests universal elements: Nations spy on each other; military personnel serve on lonely outposts, put a high value on mail from home, and get frustrated with incompetent commanders.

Tom A. Titus is a research biologist and instructor at the University of Oregon. In his spare time he is a writer, runner, gardener, husband, father of two, and seeker of wild things and the wise quiet places in which they are found. He works, writes, and forages from a home that two cats share with him and his wife in Eugene, Oregon. Writecorner Press is delighted to publish excerpts from four sections of Titus' book, Blackberries in July: A Forager's Field Guide to Inner Peace, published by Red Moons Press in 2012. The author prefaces each section with an italicized introduction.

“Late Winter Rain” is a February hike into an ancient Douglas fir grove in the Oregon Coast Range that is both the physical setting for retracing my return to Oregon and a metaphor of the complex relationships that connect us to home.

I’m a blue collar Ph.D., a bow-hunting conservationist, a bird-watching duck hunter, a traditionalist scrambling to keep up with the times, an evolutionary biologist who believes in human consciousness. I have family and friends I would die for but am often happiest when I’m alone. I’m a writhing tangle of contradictions, a roiling kettle of points and counterpoints, a stormy sea of internal debate. Yet at one point in my life I managed to wade into the center of this emotional spiritual intellectual maelstrom and emerge with a purpose: to experience deep inner peace. No problem.

To me, the idea of an internal state of serenity still seems pretty far-fetched, but I’ve learned a few things. One of those things is that my existence is like an ongoing chemical reaction; it precipitates a lot of stuff, and the bits and pieces need to settle out occasionally. So I set aside some time every February, my birthday month, to sift through this flotsam, passing the odds and ends through the sieve of consciousness, holding them up to the light, inspecting each one for some previously hidden glimmer, something that might justify the space they occupy in memory.

This morning I drive a meandering road deep into the Oregon Coast Range, where wet wrinkly ridges, narrow watery canyons, and evergreen forest are scrunched between the blue-gray vastness of the Pacific Ocean and the flat green farmlands of the Willamette Valley, a place where nine months of rain drive birth and death and growth and decay and rebirth at such a frenetic pace that all flow into a peaceful drippy singularity. Everything here either is or once was in a fluid state. Even the core of these mountains is cold seafloor pressed into beige sandstone that was riddled with red hot flows of liquid basalt that now stand stalwart and gray....

For ten years I regrew my Oregon roots by tending the “Smith River Memorial Garden” at the Johnny Gunter cabin. The practice of saving seed bridges generations of plants and people and becomes a physical, emotional, and spiritual anchor between humans and their place in the world.

When seeds are saved from plants that have grown for many years in a single place, the plants and the people whom they feed become that place. This plant-human relationship is fundamentally physical. Within a few seasons the genetic makeup of these crops is already being molded by soil and weather and human choice. For Mom’s beans, the strongest plants made more of themselves and the largest seeds were selected and planted the following year. When surplus beans are eaten, their proteins are dismantled and recomposed into enzymes that activate the myriad chemical reactions that keep our physical selves running, including the firing of our brain cells that become choices that allow the best beans to persist. So Mom’s beans have, in a very direct way, become both her and her place in this bioregion. They will also become part of everyone with whom she shares a handful of seeds, and a simple bean then becomes a fiber in the fabric that binds people to each other and to the land.

I drop beans onto the surface of the two beds, the seeds about four inches apart, marking the boundaries between each variety with upright sticks, methodically pushing the seeds into the fluffy earth with my index finger, smoothing the surface as I go. Now the beans will grow in my hands, a product of Mom’s stewardship, a digging tool welded by Dad, the Kimmel horse byproducts, and the peculiar way that the sun, now gliding to roost below the bare western ridge, shines on this ground.

“Blackberries in July” is the story of an impromptu berry picking adventure that became a formative experience in reestablishing my intergenerational ties to western Oregon. Harvesting the tiny wild blackberry that is endemic to western mountains is a celebration of the process of place.

Even in the face of pavement-induced climate change, ripe berries were in extremely short supply. Scarcity often gives birth to frugality. I skimped on taste testing, and in lieu of eating my hard-won fruit I periodically waved purple-stained fingers under my nose, sending that blackberry bouquet floating through my brain and setting my pleasure centers firing like the rapid thumping of a drumming grouse. Chemistry was never my strong suit, and I don’t know what sort of aromatic compounds give blackberries their distinctive nose. Whatever they are, wild blackberries have concentrated this essence into a very small package.

That blackberry scent coalesced into a pie that seared itself into my imagination, and I became driven by the vision of it, picking every berry with any prospect of adding to that steamy purple filling: barely ripe, partially fermented, tiny, large, or half-eaten by chipmunks. Surely this mix would give my pie what the wine folks call “complexity.” Speaking out loud, I promised the animals that I would leave some. But talk was cheap, and I searched for every dropped berry as if I had lost my wedding ring.

The rain subsided and sunlight burned slowly through the vapor. Parking at a turnout above the three-mile downgrade toward Upper Smith River Road, I discovered that here, for reasons known only to the blackberries, they were especially plentiful. I became a delirious bear, weaving from one side of the road to the other, popping berries into my freezer bag. The return to my car provided a slightly different view, revealing a few more berries. Back at the turnout and giddy with success, I allowed myself to take serious stock of the situation. Opening the rear door I placed the bulging freezer bag next to the heaping sandwich container. There was no doubt; I had enough berries for one unadulterated wild blackberry pie....

“Chanterelle Forest” begins as a hunt for wild mushrooms, then evolves into an acute awareness of ongoing cognitive dissonance and anger. Reconnecting with the natural world can resolve this angry discord, but may also wound us. How can this paradox be resolved?

We are wounded even in our isolation. Millions of years of evolution have etched into our chromosomes a need for deep connections to the land and other people that is as immutable as the rocks that have become our bones that carry us around in this green world. In A Sand County Almanac, Aldo Leopold framed our evolutionary relationship to the biosphere in moral terms. He understood that we function as moral humans only when we act upon our empathic connectedness to one another, and he challenged us to expand this concept of morality to become a moral species making moral choices with respect to both our fellow humans and our place in the community of the Earth. This requires us to become fundamentally connected to our bioregion as well as to our fellow humans. The alternative—to remain within our self-constructed, self-imposed cell, trapped in entitlement, parasitizing and ultimately killing our ecological life support—is to become biologically and morally destitute.

So we arrive at a profound and tragic paradox. We must throw open the windows, break out of our cubicle, trade recycled air for oxygen made by real trees, give up hard black asphalt for delicate green moss, dump the vitamin pills, and forage for wild mushrooms. We must travel further along the path toward intimacy with the land. But in doing these things we will be hurt. We will be traumatized.

Despite this risk, I choose the path of reconciliation. I accept that I will be damaged. But I will not be destroyed by my wounded anger. Instead I will forgive. I forgive because I must; because if I don’t then upon my reentry into the atmosphere of the living world I will be obliterated in the fire of my own resentment. Instead, I choose twisted vine maple and forgiveness, slanting autumn sun and shadows on sword fern and forgiveness, a gentle trickle of spring water over sandstone and forgiveness, a young hemlock tree growing from a sawed-off stump and forgiveness, the soft silence of an owl’s feathers and cool salamander skin and the tiny hot breath of a winter wren chattering in the salal and forgiveness. I choose to forgive self-centered human blundering and insensitivity, especially my own, even though I do not forgive easily. I choose my wife and children and friends and forgiveness. I choose to watch the landscape heal. I choose to heal myself....

Blackberries in July is available for purchase from Red Moons Press Publications, Eugene, Oregon. $12 US

Authors | Home | Top

Rick Wallach's extensive studies in literature and culture include work at Fordham University, New York University and the University of Miami. He taught literature, critical writing, and American cultural studies at Roosevelt University in Chicago and now teaches at the University of Miami. His articles and reviews on topics in media studies, American history, culture and letters have appeared in numerous journals and publications. He is a founder of The Cormac McCarthy Society, the editor of Myth, Legend, Dust: Critical Responses to Cormac McCarthy and co-editor with Wade Hall of the two-volume study of McCarthy, Sacred Violence. The following article first appeared in Southwestern American Literature, 27:1, Fall 2002, 21-36.

[Bracketed information in the article is by the Writecorner Press editor.]

Theater, Ritual, and Dream in the Border Trilogy

Rick Wallach

Cormac McCarthy’s dalliance with the theater has been long and problematical. Unlike his acclaimed novels, his dramatic works have been at best limited successes, or outright failures. A 1977 teleplay, The Gardener’s Son, ran briefly on PBS. Its publication in book form twenty years later revealed that McCarthy’s original framing devices, especially a deus ex machina called “The Timekeeper,” had been dropped from the shooting script. Production of a later stage play, The Stonemason (published in 1994), was twice derailed, once by politicized infighting among the cast (Arnold 1995) and in both cases by its own heavy-handedness and staging difficulty (Josyph 1998).1 An environmental cliché-ridden 1970’s-era screenplay, Whales and Men, remains mercifully unproduced.

Yet the theater – or, perhaps more accurately the idea of the theater – has always fascinated McCarthy, and his use of the imagery of the theater as metaphor in his fiction proves far more successful than his dramatic writing per se. Although allusions to matters theatrical do appear often in Blood Meridian,2 the theatrical trope is most elaborately deployed in the Border Trilogy novels: All the Pretty Horses, The Crossing and Cities of the Plain [henceforth these novels are noted as Horses, Crossing, Cities]. Ironically, the Trilogy began life as a screenplay for a hypothetical film version of Cities.3 McCarthy worked backwards and over the better part of a decade and elaborated it into the series of novels we have now.

The metaphor of theater is essential to the structure and thematic unity of the Border Trilogy. From the play for which John Grady Cole’s aspiring actress mother abandons him, to the elaborately staged dream ritual a stranger describes to the aged Billy Parham in the epilogue of Cities of the Plain, references to performance, theater and ritual undergird the Trilogy’s stylistically disparate narratives. Each novel depends upon theatrical tropes to launch its protagonists on their adventures or adjust their trajectories. References to role-playing invoke essential questions of personal and spiritual authenticity; the metanarrative of the Trilogy proper juxtaposes references to choreography, scripting and stage management with foreground questions about fate or destiny and about narrative itself. In effect, the Border Trilogy interrogates theatre as one among the several forms of narrative that it questions.