Selected Writings of Robert B. Gentry

Except for classroom use or excerpts in reviews, no work of Robert B. Gentry may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without permission of the author.

From CONFESSIONS AND IMPRESSIONS: GENTRY'S JOURNAL

[Bolded, bracketed information occasionally added for context and clarity.]

[A conversation with Mrs Thelma Toole, mother of the late Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist John Kennedy Toole. He committed suicide in 1969. Through the tireless efforts of his mother and with the help of writer Walker Percy, Toole's A Confederacy of Dunces was published in 1981.]

April 7, 1982 I phoned Thelma Toole several times last month, and she agreed to be interviewed at her New Orleans home yesterday at 3:00 p, m. Sue and I easily found her modest, unairconditioned bungalow next to a mortuary on Elysian Fields Avenue, about four blocks from the French Quarter.

Arriving at the front door, we heard what seemed passages from her son’s great novel, A Confederacy of Dunces. Then from somewhere inside came a commanding theatrical voice, “Please do come in, Mr. and Mrs. Gentry!” In the living room stood Mike, a huge man, twentyish and looking close to 400 pounds. Thelma Toole was auditioning him for the role of Ignatius Reilly, the main character in Confederacy, that she hopes Paramount will turn into a film. “I apologize for running overtime with this audition,” she said, and asked us to sit while she finished. Mike was having great difficulty with some lines. In a corner of the room Mrs. Toole stood in front of her walker. At 80 she appeared energetic and very much the teacher. She wore thick red lipstick and a pillbox hat of straw crowned with a feather fluff that flipped in a circle. Her floor-length, gold silk gown gathered at the neck and went up her arms in three-quarter length sleeves. Her white, elbow-length gloves were dirt-smudged and tied on her left wrist was a corsage of dead roses. She coached Mike with waves of a gold-sequined paper scepter and taps of her gold-slippered foot to stress the rhythm and force of passages. The audition ended at 3:30. She bade the big boy gracious gratitude and a fond goodbye. “He can’t do it,” she said when was out the door.

Mrs. T. I can tell from your faces you’re wondering about my attire. I’m very much the actress. Always have been! I taught speech and drama for many years. This dress I wore in the Confederacy Clones parade back in February.

Mr. G. Is this the parade connected with Mardi Gras?

Mrs. T. You could say it’s an alternative to the Mardi Gras Parade. It’s put on each year by the Contemporary Arts Center and also goes by the name Crew of Clones. It’s a mock parade. This year the Arts Center honored women in the arts in New Orleans. I was the Queen Mother of the parade. It was a nice way of featuring my son’s book.

Mr. G. Can you tell us a little about your son’s early years? His schooling, interests, development, things like that!

Mrs. T. He was very smart in school. Brilliant, in fact! In grammar school he skipped two grades. When he was in kindergarten he complained, “Mother, I’m not learning anything.”

Mr. G. When did he start writing?

Mrs. T. He wrote essays in high school and entered essay contests. He won first place in one of them.

Mr. G. I heard he wrote a book called “The Neon Bible” at age 16.*

Mrs. T. Yes. Walker Percy said that no 16-year-old could have written that book. It shows how advanced John was. The book is a commentary on Southern evangelism.

Mr. G. Mrs. Toole, would you mind if I shut the door? The street noise is—

Mrs. T. (Laughing) I’m afraid I’d roast in here if you did.

Mr. G. I’ll get a little closer so I can hear you better. Would you mind speaking a little louder?

Mrs. T. I’d be most happy to.

Mr. G. His master’s degree was in English. I assume he majored in English as an undergraduate at Tulane.

Mrs. T. Yes. He did his master’s thesis on John Lyly at Columbia. John Wieler was his director there.

Mr. G. Did he have a minor area of study?

Mrs. T. He studied French and German. And Spanish in high school.

Mr. G. When he began writing seriously, what was his writing routine and what conditions did he write under?

Mrs. T. He was a private person. He kept a lot to himself. I believe he was afraid at times of disappointing me. He wrote Confederacy when he was in the Army in Puerto Rico, 1962-63. At the time he was teaching English to Puerto Ricans. He spoke Spanish fluently.

Mr. G. How did he write? Did he usually outline? Did he do much revision?

Mrs. T. His writing just flowed. He finished Confederacy in two years. Then he started dealing with Gottlieb at Simon and Schuster. He didn’t do much revision after Gottlieb got hold of him. Gottlieb was a wretched person. He just strung John along. Then finally he told him that Confederacy wouldn’t do for publication. John got very depressed after that. I didn’t realize how sick he was. His being unable to get published was a major cause of his death.

Mr. G. Did he keep a journal?

Mrs. T. He wrote all kinds of things. I’m still uncovering letters and essays he wrote. I hope to publish a lot of it soon.

Mr. G. What about “The Neon Bible”?

Mrs. T. I’m going to have it bound and placed in the Rare Book Room at Tulane.

Mr. G. (Chuckling, shouting.) Now we have competition from the lawn mower.

Mrs. T. (Shouting.) My brother’s cutting the yard.

(Shouting continues for the next several exchanges.)

Mr. G. Who were his favorite authors?

Mrs. T. The Romantic poets: Keats, Shelley, and Wordsworth. Wordsworth’s “Intimations Ode” really appealed to him. He liked Irving Ribner and Alexander Pope, too.

Mr. G. What about Swift, an obvious influence on Confederacy?

Mrs. T. Yes Swift too, but he didn’t discuss Swift with me.

Mr. G. The letters and essays you said you were going to publish, did they suggest any literary influences on John?

Mrs. T. I’m particularly interested in the fourteen letters between him and Simon and Schuster. I really wonder if it’s wise to publish them, though.

Mr. G. You said on the phone he sketched and painted. What subjects did he do?

Mrs. T. He did a nice sketch of me. As a child he attended two art schools: Mary Basso McCrady at age 9 and at age 10 he studied at the old Isaac Delgado School.

Mr. G. As a person did he show a satirical bent?

Mrs. T. Heavens yes! He was witty, the life of the party. He liked to rib people. Would you both like some sherry?

Mr. G. That would be fine. Sue. Yes, thank you.

Mrs. T. The bottle and glasses are on the table in the next room. Please get them for me. (After all our glasses are filled.) I don’t drink much. My health is not at all good. I’ve been severely taxed. Yet I continue to work earnestly and valiantly for my son. Posterity will treat him better than the present age has.

Mr. G. I’m wondering how John meant readers to take Ignatius Reilly. You have been quoted as saying that “Ignatius is sloberino, a figment of my son’s imagination.”

Mrs. T. Yes, that’s right. My son told me this about Ignatius, “He’s not a real New Orleans person. He is used to introduce the real New Orleans people.” These people are what my son told me he wanted to write about. He wanted to write a book about New Orleans, and Ignatius was his way of railing at the pretentions and phoniness of the city. Ignatius is a booby but he’s a prophet too.

Mr. G. Will your son’s unpublished works be available to scholars anytime soon?

Mrs. T. I have been advised not to open them to the public right now. You know, under Louisiana law the father’s estate automatically gets 50% of a wife’s royalties. I have some reviews of Confederacy you may be interested in (She hands me a large envelope.). There are photographs of my son in there too.

Mr. G. Thank you so much.

Mrs. T. And I want you to have a hard-bound copy of Confederacy.

Mr. G. Oh, thank you so very much. Would you autograph it for us?

Mrs. T. I’d be most happy to. (“Appreciation and Regards from John Kennedy Toole’s Mother, Thelma Ducoing Toole, to Dear Sue and Robert Gentry”)

Sue. You are so gracious. Thank you!

Mrs. T. Now come, I want to play the piano for you.

Mr. G. This is another treat.

Thelma Toole played and sang four songs, the last one in honor of her son: “Oh Yes, He’s My Baby.”

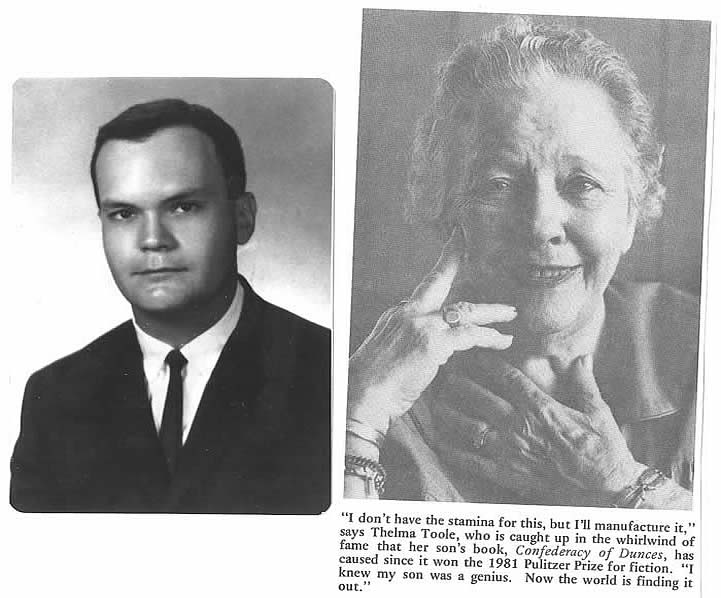

These pictures and a nice note of thanks Thelma Toole sent to Sue and me in the spring of 1982 (after the interview) when there was still worldwide excitement over Confederacy. On the back of John's picture she wrote, A Photograph of My Genius-Son, John Kennedy Toole, from His Mother, Thelma Ducoing Toole to Mr. and Mrs. Gentry. Apparently Sue and I did not introduce ourselves to her with our different last names. In her note she said, Recently, pressures have been steadily mounting, and I am excessively taxed, with a serious toll on my health. But, I continue to work valiantly and earnestly in the world for my son. I recall that I warmly thanked you for the beauteous roses, or did I?? If you have time to answer this note, please tell me so. It has been so rewarding to meet you both, and, I felt we established a sweet rapport! Fondly, Thelma D. Toole The picture of Thelma is from Applause, a publication of the New Orleans Public Schools.

*The Neon Bible was adapted to film, written and directed by Terence Davies and filmed in Georgia. It was first shown in France in 1995 and then in England the same year.

New York, New York

July 24, 1983 Sitting in Penn Station, I must write these impressions while they’re fresh. Two young guys are holding hands. They’re slim and wear tight short shorts; sleeveless, shoulder-strap undershirts; sneakers and calf-length white socks. Men and women gaze and gawk at them. They seem oblivious to anything but themselves, their pectorals prominent, their crotches bulging. Now they giggle and slap each other on the back and chest. I can’t hear what they’re saying. If they dolled themselves up, they might pass for pretty girls. Maybe they really are in drag.

Earlier, I saw parts of dirty, defiant 7th Avenue. A black power group shouted about “the ignoramuses of the world, the European white people. It doesn’t make any difference whether you’re British, French, German, Spanish, Czech, Hungarian, you’re all the same. You came out of the bowels of the Roman Empire and you’ll be destroyed like it was because you’re all ignoramuses, you and the Russians, and you’ll both destroy each other.” Thus they bellowed, a bunch of muscular, tough-looking men in their late 20s and early 30s. I stood across the street, watched them, jotted a few notes. They quoted from the Bible and twisted it to suit their rhetoric. They ranted and raved at sullen whites who rushed by, two trotting and clamping their hands on their ears. “Yeah, go ahead, stop your ears,” a black yelled. “You don’t listen to truth. That’s your natural way. You never did listen and you never will.”

As much as I loathed their attitude and words, at least one thing they said hit home. If the U. S. and Russia don’t settle down and quit bomb-rattling and threatening each other, if we don’t get sane and some peaceful sense, we probably will destroy ourselves and the world.

The area around Penn Station and Madison Square Garden (32nd St. and 7th Ave.) is littered with trash. Bums slouch and slump along railings outside the station. Several sleep on drab concrete near the Garden entrance, hands clutching their genitals as if these things were all that mattered, asleep in tattered clothes and dirty beards and torn socks, out of their booze-blasted, drug-dregged minds while junkies and pushers and whores step over and around them.

Down in the Penn Station Men’s Room, blacks and whites wink and blow kisses at anyone who glances their way. Toilet-paper the stool as best I can. I dump warily, wallet tucked under my arm, afraid some needle-punctured arm will reach under the partition and slip it out my pocket if my pants drop. Keep them around my knees. Walls of my stall are full of graffiti, a few witty, most ignorant, stupid. Two sneakers enter the stall next to mine followed by two more sneakers. I hear giggling, see shorts drop to ankles. Sneakers on sneakers—heavy breathing—moaning. I wipe, jerk up my pants, rush out to await my train.

It’ll be a while before Amtrak announces mine. A well-dressed man fishes in a garbage can for a newspaper, brings it over, sits next to me and starts reading. I’m roasting in Penn Station. AC must be off. I drift outside again, sit on a railing, light a cigar. A black kid asks for “a smoke.” I shake my head. He asks others, black and white, but doesn’t ask any Orientals. All turn him down.

August 3, 1985 We’re staying at the Hotel Barbizon at the entrance to Central Park South. Compared to the townhouse in North Conway (which we exchanged this year for our place in North Carolina), the Barbizon is feces. Last night we slept on short-lumpy-dippy beds in a cramped room. When you flush the small commode, mess splashes your butt. This hotel robs you at more than $80 a night. Contrast it with the townhouse in New Hampshire or our time-share condo in Carolina where we have two levels, two baths, full kitchen facilities. In NH we had a television upstairs and one downstairs. Of course, all this is the height of bourgeois extravagance.

At the strip of 8th Ave. near Times Sq a guy slept across a 46th St. sidewalk. Theatergoers had to step over him. His clothes were rags, he was shoeless, his socks full of holes and his pants shit-sodden. He reeked. An empty liquor bottle he clutched to his chest as if it were his only friend on earth. On 47th St. another wretch pawed in a trash can and pulled out two cola cans, no doubt bent on selling them to recyclers. In the face of this mess, I feel sad, disgusted, helpless.

Strolled Central Park this morning and then saw “The Figure in 20th Century American Art” which the Metropolitan is featuring at the National Gallery of Design. Two of my favorites in this one: Edward Hopper’s Office in a Small City and Gaston Lachaise’s Knees. Black woman with strawberry blonde hair just spit a big gob a few feet from us. Sue, deep in her diary, didn’t notice, thank goodness. See such mess a lot and you get numb....

The band plays in Central Park on this sunny day filled with pigeons and people and cars and horse-drawn carriages. This afternoon Sue had Mocha Crème and I Crème au Chocolat at the Café de la Paix just across the street from the Barbizon. These drinks cost an outlandish $13.75 because the waiters wore tie and tails and we were sitting in the outdoor section. In other words, they charged us out the gazook for a pseudo piece of France. Sue: “This is probably the only place in the Western world where you can sit outdoors, be served by waiters in tuxedos, and smell shit from all the horsey carriages clomping by.”

I love to rail at New York and confess tingles of excitement every time I come here. I love and hate the place and wonder why I find the freaks and clowns and jerks and pathetics so fascinating. I have to wonder why in this wealthy nation and cosmopolitan city people get the point where they sleep on sidewalks or dig in trash cans or dress up like bizarre clowns. There are reasons of course, but they don’t satisfy me....

Aug. 4, 1985 At Village Corner, an outdoor café in Greenwich Village. The menu promotes the food as “seedy but stimulating.” Sue and I sip beers at $1.50 each, much better than the outdoor beer price at the Café de la Paix attached to the St. Moritz Hotel. A guy in dirty clothes and red ball hat digs in a garbage can as a woman in pantaloons strolls by. An ammo belt holds up her pantaloons. She has a burr haircut and saunters like she’s the coolest thing in town. Loud guffaws erupt from two tables. Other tables are quiet with gays romancing. One has a remarkably pointed head. Another strokes the arm of a swarthy Hispanic boy and with the other hand dips his fingers in his beer and wets his mustache with them. The garbage guy finds nothing he likes and pulls his battered red wagon away. Another pointy head saunters by with a woman who’s wearing white-mesh knee socks. Across the street a Mohawk head appears, Hell’s Angels jacket slung over his naked shoulder, his unzipped boots flopping as he struts by two girls....

Scenes and thoughts in Massachusetts

Idyllic Turner Falls

July 15, 1986 Have to think hard what day it is. Days blend together when you’re on holiday or at workshops. It’s Tuesday and I’m at a rather bland park in Turner Falls, 4 miles from Greenfield. The weather has finally brightened up after almost 3 days of chilly, dreary rain. Don’t want to journal but something compels me to—some mysterious daemon drives me on.

Turner Falls Lake (I think it’s a lake): Few yards in front of me a man fishes from the bank and shows a boy how it’s done. Sun sparkles off the water and a breeze slowly spreads wavelets. Distant sailboats drift into my picture while a woman sits in a lawn chair reading, her feet on a smooth boulder. Behind her a carousel goes round and round to the tune of children laughing and playing. Across the lake two-story houses look as if they have always been there, natural frame reliefs in a greenscape of rolling hills, not high or awesome, but plain and gentle these hills as if this scene could be none other than what it is, at first very common, even bland as I said, then growing on you: soft, green grass waving in the breeze, pine trees and boats and leisured people blessed in a still life of summer. Things move or don’t move in the eyes of the viewer who is both creator and created, who if he were a genius could take line and color and freeze this scene for the ages.

Across the lake three boys in swimsuits laze on a high ledge; now they shuffle. One eases to the edge, bends his knees and leaps up and out, his figure fully extended like a bird gliding over the surf in slow motion then dipping and diving down to knife the water in a plunging splash. I think of Eakins’ The Swimming Hole and then of Knoxville [my hometown in TN]and Chilhowee Park, the lake there in 1947 and the boy I was then in those summers I thought would go on and on. And now the dream returns again, it all returns again: the sun and lake and hills and houses but most of all the peace…the warm, precious peace....

Atop Poet’s Tower

July 17, 1986 ... 1500 feet above Greenfield [MA], I’m Lord of all the town. I wave a hand and down below I get a vacant field complete with diamond, backstop and bleachers. I blink and five tennis courts appear. Players look like tiny toys. I snap my fingers and two players amble and two more bat violent volleys; others lunge and dash and cut around right and left court. All I make rational in form but insane in aim for batting white dots back and forth at each other. People and cars in the distance I render insignificant, even absurd. All around I’m enclosed by hazy hills and suddenly I feel less creator and more captive. Who knows what I am in of all this? The distant hills look blue; nearer ones varying shades of green. Oaks and maples, pines and spruces partly hide some houses, fully hide others. I gaze and marvel at the prince of Northern pines, the stately blue spruce.

A woman and two kids interrupt my reverie. They stay a few seconds, see nothing and leave. Now two teen boys come stomping up. One mouths a can of Slice. The other snaps, “I could whip a tennis ball way out there.” His friend spews a gob that goes down down, white speck of spit before it vanishes. I’m the Lord of Misrule and these slobs are my unwelcome lieutenants. Maybe that’s why the sun’s retreating into the misty sky—it doesn’t like us. The day turns fuzzy, grayish green. My lieutenants go bounding down the steps like apes. In a minute they’ve seen nothing.

Across my ball field I nod and brick buildings with flat roofs appear bordered by strips of asphalt. Only a few trees in this area! Did I really condemn them to grow stunted beside silly streets? Sun struggles to shine then dims behind haze again. I walk to the other side of the tower to see the Green River still as glass, trees reflecting in the water like little gazers mesmerized by their own images. Maybe Narcissus was a tree.

I puff on a Bering cigar and wonder if anything in nature gives a damn about me. How could it if I’m the Lord of Misrule? Have I become Lord as defense against indifferent nature? Oh I don’t lament this indifference. I seek to join it and blend with it. I cast my mind up and out—over the land I float, drifting down down into the trees. I try to blend into a blue spruce but it won’t have me, nor will the earth receive me—yet. I cannot separate from self—still crave my certain self—still cling to me of things and rebound to me of this Tower.

Down below one ape throws his can down the hill, laughing like a loon as it clanks and clatters against the rocks. If reality is only what we create by perception, why in the hell did I create these cretins? Why didn’t I leave them as clods? I start to yell at them but spy a handsome cameraman slinking up the steps. We greet with perfunctory hellos. He scans about with his device then slithers back down the steps hunching and crouching like a voyeur filming an orgy. In 45 seconds he’s seen nothing. Is he a newsman? Will I appear on the evening news? Nature doesn’t care and neither do I. Cameras bug me. They get in the way of my eyes....

Veritas Supra Omnia

July 21, 1987 My birthday at Stoneleigh-Burnham School in Greenfield where Sue and I are on this year’s staff of the National Institute for Teachers of Writing. I try not to think what day it is, but everything here reminds me. The sign at the entrance to the school proclaims “Veritas Supra Omnia.” What is my “veritas”? Damn it, I know very well what my veritas is. I see it in the circularity of this place. I see it on this entrance sign: the drawings of an owl in a lighted lamp and fluttering banner on which is the “Veritas” motto—verbal and visual meaning caught in a circle, a tight ring that cages wisdom and traps truth in a dot of the mysterious all.

I see my veritas as I stroll this campus, in the riding rings where nubile girls ride their genitals on the backs of horses they work. Round and round the rings they ride, cantering out and around and back to where they began and doing it all again and again. I see it down the hill there in the stagnant pond over which willows hang heavy and weep. I feel it in my varicose veins and in this heat that cut short my walk down Federal St. and sent me back to where I began. I see it in the dust these horses kick up, dust that powders things a sickly sallow, curls like smoky specters above the riding rings and drifts far beyond water hoses that wheeze and rasp like dying men. Almost breathless from the heat, I keep trudging and finally reach our cottage. Before entering, I stare at the dark woods and pinch my clammy arm. “Happy birthday,” I whisper.

July 25-26, 1987 The Institute has been going well. The participants have been enthusiastic about our workshops on the one-to-one conference method. My presentations on the journal and essay questions have gone over so much better than I expected. I think I’m finally conquering my inferiority complex about workshopping.

As the Institute ends, I see another veritas no less true than the stark one I saw July 21. It’s the veritas of a private-school setting for a public-school meeting, the truth of Stoneleigh-Burnham, the rhythm of horse and rider, the harmony of human and animal, the fresh glow of girls in riding caps in summer and sun. It’s the veritas of teachers eager to share and learn together, of North and South blending so well. It’s the veritas of the jokes these teachers tell, the hilarious poems they write to each other, like those that jest about how Yankee Doodle and Johnny Reb gulp their grits.

It’s the veritas of the recital last evening at Blessed Sacrament Church given by these teachers themselves, the truth of Bach and Couperin, of Jewish-American Joy Pitterman and German-American Hartley Pfeil singing “Shalom Rav,” the beautiful song of peace. It is the veritas that ended the American Civil War and the Holocaust. It is the vision of an age-old dream in the process of becoming in the United States. And in this vision, my friend, lies my fervent hope that you will be reading this a century from now, in another time, in a better place.

Wretched Jersey Turnpike

July 14, 1989 Leave Jax for the Northeast where Sue will help run the Master Teacher Seminar in Greenfield, Mass. while I'm attending the Conference on Creative and Critical Thinking at Wellesley, Mass. As usual the drive discomforts me, especially the Jersey Turnpike where wretched service centers pop up every 15 or 20 miles. Hordes pile into these centers to fill their bellies and gas tanks. A few companies—like Texaco and Shell for cars and Roy Rogers for food—hog all the business. The few clerks I've dealt with have been curt and impolite. One Texaco gas jockey smarted off at me when I asked if a pump was self-service (I saw no signs indicating the kind of service). We argued heatedly and ended up calling each other "assholes" (he said it first). It seems funny now but could have been a serious situation.

Beauty and "Metacognition" at Wellesley, MA

July 16 - 21, 1989 At Wellesley College I’m staying in a dusty dorm with cobwebs on the window sills. The bed is comfortable enough. A student told me that the tuition here is at least $20,000 a year, about $100,000 for a four-year education. The campus is one of the most beautiful I’ve ever seen: 500 acres of smooth greens bordering Lake Waban, around which runs a nice path for strolling and taking in nature. Like the college, the town of Wellesley thrives on natural and cultivated beauty: large 2-story homes, well kept lawns, various flowers—some in gardens, others borders of colorful blooms. People here move with a certain ease. Maybe a better word is grace. I’ve seen no jerky or loud folks. I heard some rock music coming from a dorm building where the kids looked high-schoolish in age and manner—maybe visitors getting the feel of the school. The rock group was mild really and didn’t begin to suggest mob behavior.

I have two professors who have been presenting "a framework for approaches to critical thinking." (their words) They teach from 9 to noon each day, talk mostly in esoteric tongues, and offer little of practical value for the kinds of students I teach. To these profs thinking skills come in three types: micro skills, macro skills, and meta skills. "Metacognition" is one of their favorite terms, meaning to think critically about one's own thinking. In the afternoon (1:30--4:30), an attractive woman gives us some of her ideas on critical thinking and literature. She dwells on myth and literature and has much praise for Annie Dillard and Joseph Campbell. I haven't learned much from her either, but she's easier to talk with than the two theoreticians in the morning. Today she wore a transparent black skirt with a sheer white slip under it, sat on the desk, occasionally squirmed as she lectured. Once she threw one leg over the other but not fast enough to hide mid thigh. I wondered if she were an exhibitionist warming to student stares and the feel of the desk. A woman sitting next to me whispered, "Isn't that the most provocative skirt you've ever seen?" I said, "Oh yes, and it adds another level of interest to the class."

John Dillinger and henchmen in Phlox, WI, my wife's hometown

Dec. 15, 1985 Al Koeppel is a tall, thin man of 77 who has borne more than his share of life’s troubles with dignity and grace. He has lost two sons and two grandchildren in car crashes and now his wife is in the middle stages of a major disease. He cares for her constantly, taking her to the bathroom, dressing and sometimes feeding her. Despite all this, he is a man of good humor who always has a joke handy. He’s an excellent source of information about the Midwest of the 20s, 30s and 40s. Here are some memories in his own words:

“Some of those big-time gangsters used to come through Phlox. There was Baby Face Nelson. He called himself Charley Rand. He’d pull up to my filling station and get some gas and be as nice as he could be. He could talk on anything the folks around here knew, like making maple syrup.

“John Dillinger’d come through too because he had an Indian girlfriend out in Neopit [in the Menominee Indian Reservation]. Her name was Evelyn Frechette. He had a chauffeur who’d drive him and Evelyn around. They’d stop a lot at my station to get gas. One time on Easter Sunday my father took them to church with him, one on each arm.

“I don’t remember exactly whether Charley Rand was really Baby Face Nelson or Pretty Boy Floyd. I’ll have to check that out at the Antigo History Museum. I do know Charley Rand, as we called him, would hang around the station, shoot the breeze with all us fellas, and he’d make himself right at home. He even helped me pump gas once when we were very busy. We never knew where he went at night, but come daytime he’d show up often to get batteries charged. He’d often keep two batteries charging at my station. He said he liked to listen to his car radio a lot. We didn’t know who these guys really were till they got killed and all the news came out in the paper.

“Back around World War I we had prostitutes who made a regular living out of Phlox. There was a regular family of ’em: it was first the mother, then the daughter when she was old enough to get customers. Everybody knew who the whores were and accepted it because there was a saw mill and hotels in town and lumber camps around and the single men had to have their women once they got through work.

“Yes,” Emmy said, following her husband’s memoir pretty well... “and those naughty ladies made it safe for decent women to walk the streets.”

“Later in the 20s and 30s,” Al continued, “the demand for whores got so great they were shipped in from Chicago and the big cities; they even came from smaller towns and were loaned out to whore houses around Phlox till the demand went down. For a while these girls were coming in all the time, but when the saw mill burned down all that whore-stuff stopped. That was way before World War II.”

Ice Fishing in Phlox

Dec. 22, 1988 ...Observed an ice fisherman on Phlox Pond. Here and there along the pond you could see little huts to which the fishermen retreat to avoid the blasts of bitter-cold wind. The wind chill factor must have been 10 to 15 degrees below zero. I took the cold pretty well except my face which kept stinging from the icy gusts. The guy I watched had such tough hands he fished without gloves, took the fish off the hook barehanded and pitched them in a bucket which his little daughter was holding. As soon as the fish hit the air, they moved very little. Cold must stun them. Someone said the ice was about a foot thick. There were plenty of holes which men had drilled earlier in the day and left. They drill with augers, some hand-powered, others gas-driven. When they sit in their huts (warmed by little stoves), they attach an orange flag to their line; when it falls they know they have a strike. To ice-fish one has to be rugged and hearty....

Struggling in Wisconsin Winter

Dec. 15 - 26, 1990 ...In Wisconsin this time: first a week at Olympia Village, a winter resort in Oconomowoc. Driving in Milwaukee, we saw a bumper sticker that said, "Wisconsin, the Land of Cheese Heads and Beer Farts!” In Oconomowoc (about 40 miles from Milwaukee) I saw another bumper sticker that said, "My Ex-wife's Car Is a Broom." A tree right outside our apt. at Olympia Village still had cherries on it in dead winter. Some looked ripe, even edible, though surely not. This situation struck me as analogous to old age.

"The cold and bloody North!" my mother used to say about the weather she endured when she lived as a single woman in Chicago and worked at Marshall Fields. Well, we're really living through the same during these few days in Phlox. Garages and service stations throughout most of this state are working overtime trying to get cars and vehicles started. We hear report after report of pipes freezing up. Plumbers spend most of their work time unfreezing pipes. You walk outside and a wind chill of -30 blasts you in the face. My damned knee has frozen up. Its arthritis just loves this cold. I can't fully bend the leg when I walk, so I walk crooked. A few minutes walking like that and I must look like a weird gimp. I know it hurts like hell so I don't do much walking outside. Christmas night it was 25 below; next day it didn't get above -10.

Strangest thing: flies in the upstairs bedrooms of the house! Scads litter the floor and window sills. Some hang upside down on lamp shades; others stick to walls. Some crawl along the sills near the window panes that are frosted over on the inside. The cold soon kills them or knocks them out. "I've never seen anything like this in all my years in this house," my wife said. Her father said, "I scooped up a bunch of those flies and threw 'em in the toilet. I thought they were dead, but they started swimming around in there...."

It was nerve-wrecking driving to Milwaukee on Highways 45 and 47, both of which had many ice patches. We'd be driving along on a clear stretch and suddenly run into dangerous patches of ice. Once the car hit a patch and swerved a bit, scaring the hell out of me. Highway 41 was pretty clear, though....

Langlade County Fair in Antigo, WI: Pig Wrestling.

July 24, 2008 Thousands milling around, many farm and blue collar folks swilling beer and soft drinks, chomping brats, hotdogs, elephant ears, funnel cakes, and other junk.... Kids and young adults shriek on rides. One ride’s a gigantic windmill arm whirling screaming bodies up and around and upside down. Sue and I are with her brother Tim and his pre-teen son Adam and we join the orgy, we three adults drinking dull lite beer, Adam a Coke. Sue and I gorge on elephant ears and I add a funnel cake. These things nothing but fried dough. Brown and powdered sugars coat elephant ears. Acid starts sizzling in my belly. It’ll be Mylanta tonight. Oh what the hell, we’re here like all the rest, for fun....

We get choice seats in the grandstand. The MC stands in a tower overlooking a small pen, the place of action, a barrel in the center. He pleads with people to get seated. “No standing in the aisles. No loitering at the fence.” Finally, after a half hour delay over 3,000 butts are seated. Make that 6,000 plus buttocks. Thirty-two three-person teams crowd around a pig truck. The teams are young and frisky, 17 male and 15 female, dressed in all kinds of comical garb. One male team wears tutus. A female threesome preens in prom dresses. On the other side of the pen another pig truck, a long tube-like enclosure attached to the back of each vehicle for pig entry and exit.

“OK, folks, it’s pig time!” bellows the MC. “Each team has 45 seconds to catch the pig and put it in that barrel. No pulling the pig’s tail. No grabbing the pig’s snout. Attendants lead the pig out one truck into the ring and take it out of the barrel and into the exit enclosure.” An attendant quickly hoses the pen. A male team enters. I don’t get their name. The pig toddles out. It just stands there, confused by human hullabaloo. “OK, folks, let’s have a countdown!” yells the MC. We howl out the count. On 3 the team rushes like hulking wrestlers slipping and sliding and grasping and catching the poor porker and dumping it in the barrel in about 20 seconds. The ritual is the same each time as teams with names like Three Stooges (male), Peace Lutheran Piggy Catchers (male), Hog Heaven Hotties (female), and Raggedy Hams (female) try to be fastest and best. Here comes Promiscuous Prom Pig Pouncers. The gals stagger and stumble and slosh after their pig. Two totter-tromp like old ladies as if they’re afraid to touch their “prey.” One Pig Pouncer trips and falls. Two bump and bounce off each other. After 45 seconds the gals are disqualified. They don’t seem to mind. They climb out of the ring slime-smeared and guffawing. Wonder if their messy dresses can ever be cleaned.

Bacon Mackers does nicely under 10 seconds. Paul Bostwick, brother of Mike, Jessie Koeppel’s (Sue’s niece’s) fiancé, is one of the Bacon Mackers.... Many fans leave before it’s over. We stay the course to see Team Porkies (men of the Antigo Fire Dept.) declared grand winner with a time of 7 plus seconds.

The Great Wife-Carrying Race, Minocqua, WI

Sept. 20, 2008 A bunch of slim younguns in their 20's and 30's line up (I saw a couple in their 40's; they really struggled). Each guy loads his gal this way: her crotch on his neck and butt to the back of his head, he holding her legs thrust out from his face, she hanging face down his back, clinging to him wherever she can get the best hold. Whistle blows and off they go rushing around hurdles (or jumpin' em if they can), splashing through thigh-high water, huffing and puffing up a steep hill to the finish line. I forget what the top prize was; there were plenty of prizes, ranging from 100 pounds of potatoes to 100 pounds of manure. We got interviewed by an NPR reporter, a woman who, like us, was enjoying the whole thing.

I remarked, "If Gloria Steinem were in her halcyon days, she might want to give this a go with a younger feller, if his wife could spare him for a run."

"Do I hear South in your mouth," she asked chuckling.

"Yep, Tennessee! And I tell ye, maam, my home state's got nothing on Wisconsin." I started to tell her it might, only because of the legendary One Legged Man at an Ass Kicking. Some locals swear this event occurs every four years at Dixie Lee Junction where the one-legged man swings from a tree and punishes the backsides of backsliders. But discretion grabbed my tongue and held it tight.

University of Wisconsin School of the Arts, Rhinelander, WI

July 25-30, 2010 An annual week of teaching and learning, featuring arts, crafts, music, literature, drama, and other things, even blacksmithing. You can get college credit for a number of courses. I've taken playwriting courses and this year had my best learning experience yet at SOA in Body, Mind and Spirit Practices from Around the World, an experiential course taught by charming Elizabeth Lewis who also teaches at Alverno College in Milwaukee and UW Waukesha. Body scans, deep breathing, meditation, activating energy centers (chakras), acupressure, mandalas, finger holds, hand massages were some of the practices we did. I'd had a few of these before from a highly skilled teacher, my sister-in-law, and thus was well prepared to expand my learning under Elizabeth's excellent instruction. At the end of the course Elizabeth gave each of us a card on which appeared the following in a circle:

Mandalas

The sky where it touches the earth

is a circle. The north star awakens in the

nest of night. Seasons form a great circle in their

changing, always coming back to where they were.

Our lives are circles from childhood to childhood.

Fists take the form of fully realized worlds. Birds make

their nests in circles for their religion is the same as ours.

My backyard is a yoga studio, the snow-covered earth a

practice mat. Looking east over the grey-washed lake, five

white tailed yogis salute the sun. On inhale antlers lift, on

exhale antlers bow, puffs of chilled breath touch air then

are gone. The seasons form a great circle where the earth

touches my yard. Outstretched hands can form fully

realized worlds. Life is a sacred circle wherever

Spirit moves. We all honor the same creator.

We always come back to where we are.

Elizabeth Lewis (2009)

Animals, Langlade County Fair, Antigo, WI

July 31, 2010

We've been attending this event the last several years. We like the 4-H arts and crafts, flower arrangements, cakes, bakes, and square dancers. As an eighth grader, Sue won top 4-H prize at the fair for her loaf of bread. That year she was the area's best public speaker and went on to compete at the state level. I especially like the Fair's animals. Some wonderful Guernseys and Holsteins this year, a number entered by young girls! Spying an udder full and veiny, I felt my fingers twitch and I was on that New Market, Tennessee stool again under Lady, Ross McNish's favorite heifer, Ross hovering over me.

"Don't grab or jerk them things, young Gentry. Git ye some rhythm thar. Keep that thumb and forefinger top the tit; don't want milk goin' back in her. Awrite, you're gittin' it. Lady likes Eddy Arnold. Ye know Cattle Call?"

"Not well enough to serenade Lady. I can't yodel either."

Ross let out a yodel almost as good as Eddy's best and followed with "The cattle are prowlin'/ The coyotes are howlin' /Way out where the doggies roam/ Where spurs are a jinglin'/ And the cowboy is singin'/ His lonesome cattle call...." He sang the whole song, yodels and all. Lady loved it. Wasn't long before squirts and squishes became a bucket of fresh milk, 101 degrees Fahrenheit! We let it cool a spell. Then Ross and I each had a glass full of the richest, tastiest cow's milk I've had anywhere.

Pigs are my favorite animals. This year the Fair's pig barn housed some fine ones and young girls were among the entrants. If you're not a devout vegetarian, you might find some of the signs over the stalls clever and amusing. "Samson," read one. "A lean, clean, bacon machine." Each stall gave the pig's name, its sire, the entrant's name and hometown. In admiration, one guy was rubbing the back of a hefty, pink porker as it poked into a pan of finely ground feed. I added two caresses to its back; the skin felt tight and nipply.

"I always wanted a pet pig but never lived anywhere where that was doable," I said.

"Chickens are my favorite," he said. "If I could, I'd have a whole field full."

[In August of 2007 I took the following piece from my journal and posted it in segments on the Cormac McCarthy Forum. It has since been slightly revised. A growing number of scholars and discerning readers rate McCarthy America's best living novelist. Yet in 2012 he was again not among the American nominees for the Nobel Prize. I comment on this matter at the end of this article.]

A Comparison of Thomas Mann's The Magic Mountain and Cormac McCarthy's Suttree

Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, Cormac McCarthy’s Suttree—I thought I knew why I wanted to talk about these works—for their “modernism” I told myself. Upon reflection I find great difficulties with this approach. First, after much study of Western modernism and its creators—artists, thinkers, scientists—and critics, I must be honest with myself (and anyone reading this) and say that I’m no longer sure what “modernism” is except that “newness” seems to be one its salient characteristics, if not its overarching ideal. In this sense Suttree with its esoterica certainly qualifies as “modernist.” Mann, however, recalls earlier novelists in his use of devices like the narrator-commentator who takes the reader into his confidence, calls the protagonist “our hero,” occasionally intrudes and transitions like this: “the reader can believe us when we say…”; “we let the curtain fall now, to rise one more time.” Yet Mann’s brilliant focus on time, nature, music, nationalism, sickness, health, medical institutionalization, his survey of ideas and arguments and philosophical currents that helped to push Europe into World War I, his use of Nietzsche—all these elements stamp The Magic Mountain with the indelible mark of modernism.

Another difficulty in arriving at anything like a workable definition of modernism is that it began sometime in the mid to late 19th century and may still be going strong. Depending on which scholar you read, modernism as a cultural movement ended in the late 50’s, or about 1963 (a watershed year: the murder of JFK, ground-breaking works like Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique), or in the early 70’s, or is still with us. I think you could make a pretty good case that “postmodernism” is really evolving modernism inclusive of globalism, multiculturalism, high technology, and other relatively recent developments.

Still another difficulty for me in dealing with modernism is the extremism of some of its leading figures. The Futurists, for example, celebrated modern technology in a number of dynamic paintings. Influenced by Nietzsche, they also scribbled wild manifestos that had he lived to read them might have cheered Nietzsche or sent him screaming out the door to hug another horse. Arguably, the most notorious piece is F. T. Marinetti’s War, the World’s Only Hygiene (1915). Written at a time when Europe was hell-bent on committing its first act of 20th century suicide, this thing reminds me of something Judge Holden, the arch-villain of McCarthy’s novel Blood Meridian, says, “War is god” (249). Ezra Pound’s optimistic dictum “make it new” resonates with belief in the power of art to invent, improve, transform. Yet he took his ideal and marched backward with it into bloody fascism. Film pioneers Sergei Eisenstein (Potemkin) and Leni Riefenstahl (Triumph of the Will, Olympia) used their art to support regimes that murdered millions. Is “extremist” too mild a term for these movers and shakers? Maybe fools or schizoids might be more to the point.

Yet, who but a politically correct enthusiast would deny them their rightful places in art’s pantheon. I think of other modernist lights and their defects: T. S. Eliot’s anti-Semitism, for example, William Faulkner’s rash statement about racial conflict (''If it came to fighting, I'd fight for Mississippi against the United States even if it meant going out into the street and shooting Negroes.''). As far as I can tell, World War II and the Holocaust cured Eliot of his prejudice. Thankfully, his “Four Quartets” boosted the spirits of many of us sick of war and disillusioned by modernist excesses.

Those who have almost succeeded in dumping Eliot in the dustbin because of his pre-war backsliding do literature and culture a grave disservice. Shame on you! As for Faulkner, certain black aesthetes tried hard to dump him and Mark Twain. Fortunately rational heads prevailed, including insightful African-Americans, and helped to preserve the reputation of these great writers. Let's hope that Eliot has such rescuers! Anyway, in all fairness, it should be said that Faulkner remained a gradualist on racial integration (and in this respect on the wrong side of history as did many whites then). He died not long after he made the inflammatory statement. In fact, he passed several years before the worst of the riots.

Back to Mann and McCarthy. I have no particular reason for discussing The Magic Mountain and Suttree except that they fascinate me with their striking similarities and differences. A summary of Mann’s novel follows:

The Magic Mountain is set in the decade before World War I. The story opens with Hans Castorp, the protagonist and a young German engineer in his early 20’s, about to embark on a shipbuilding career in Hamburg, his hometown. Before starting his career, Hans decides to visit his tubercular cousin, army Lieutenant Joachim Ziemssen, who is trying to get well at a sanatorium in Davos.

Davos is a quaint town located high in the Swiss Alps. I enjoyed two visits there before I read Mann’s novel. When I began the opening chapter years later in Jacksonville, FL, it immediately engrossed me. It wasn’t long before I became one with Hans, both of us transported from flatlands near the sea to the beauty and rarefied air of the Alps and the sanatorium (called the Berghof in the novel), a little world that unfolds as a microcosm of pre-war Europe.

While visiting Joachim, Hans gets what seems a minor infection and fever. The trouble won’t go away. Behrens, the Berghof’s chief doctor and director, diagnoses it as symptoms of tuberculosis and persuades Hans to stay for treatment. Hans stays seven years. During this time his militarist cousin dies as a result of leaving the Berghof in a weakened state to engage in army maneuvers and exacerbating his condition. Joachim’s death is one of many experiences that deeply affect Hans. He matures; learns about art, culture, politics, human frailty, disease, death, and love. His principal teachers are the secular humanist and encyclopedist Lodovico Settembrini, the apostate Jew and Jesuit absolutist Leo Naphta, the medical director Behrens, the magnetic hedonist Mynheer Peeperkorn, and the elusive Russian beauty Madame Chauchat. (Her French name translates as “hot pussy cat.”)

The novel concludes with the beginning of the war. Hans is drafted into the army. We last see him on a battlefield, one of three thousand troops charging into deadly fire to try to retake a nameless hill. Hans is singing to himself about love as he stumbles on. It doesn’t look like he will survive.

The Magic Mountain combines realism, autobiographical touches, and allegory. Mann’s narrator functions like a kindly father-professor sitting at the reader’s side to help us understand his “hero” and all the situations that affect him. At the beginning of the story, Hans Castorp is a provincial young man with a narrow technical education. Through his disease and experiences at the Berghof he gains greater understanding and insight. In Mann’s words (in his afterword for the 1927 English translation), “what [Hans] came to understand is that one must go through the deep experience of sickness and death to arrive at a higher sanity and health….” Allegorically, the Berghof is Europe: beautiful, sophisticated, learned, and sick. Hans and gung-ho Joachim are Germany, pressured by East and West, acted upon by forces it helps to unleash but can’t control.

Suttree combines realism, autobiography, and allegory. With its loose episodic structure and lack of chapter divisions, this semi-autobiographical novel defies clear summary. Cornelius (Bud) Suttree and the narrator are two sides of Cormac McCarthy interwoven with considerable fiction. Rather naïve, Bud throws himself into situations that almost destroy him. Like Hans Castorp, Bud goes through deep experiences of sickness and death to arrive at what he sees as complete selfhood: “I learned that there is one Suttree and one Suttree only.” (461) Like Mann’s narrator, McCarthy’s is learned, a keen observer and reporter of copious details in the physical world. Unlike Mann, McCarthy does not reach out to the reader. More complex than Mann’s, McCarthy’s narrator is aloof, a master of disgust, sometimes in Bud’s head, mostly out. Allegorically, Knoxville is a doomed Atlantis, a prison, a hell that will destroy Bud if he stays there. McCarthy is more surreal than Mann. For example, after the witchy Mother She gives him a good hexing and humping, Bud knows “what would come to be that the fiddler Little Robert would kill Tarzan Quinn.”* (430) [Quinn, the brutal cop in the novel, is based on a real person with the same nickname, "Tarzan.” See endnote for details.]

Epiphanies! We have all had them in one way or another. Consciously or subconsciously, in daydreams or night dreams or both, or fully awake in deep concentration on something—in any of these situations an epiphany may come to us, sometimes suddenly with no apparent cause, other times after an accumulation of intense, closely related thoughts and deeds. Either sudden or the result of cumulative forces coming to a head, the epiphany is revelatory, to some degree awesome, insight-producing. We see deeply into people or places or things. If the epiphany is especially powerful, we see deeply into all these elements, even into what we think is the real nature of the world (of course, we could always be mistaken). Epiphany itself doesn’t last long. Its effects may be short lived or long-lasting, life-changing.

In the chapter called “Snow” (Magic Mountain, 460-489), Hans Castorp experiences the Alps in ways that culminate in a profound epiphany for him. Hans has enjoyed sitting many a wintry day on his balcony “playing king” of a wonderland of snows and forests and mists and fogs and magic mountains that disappear “in the misty phantasmagoria” only to be freed of clouds and appear again in wondrous fragments. But he wants “a freer, more active, more intense experience of the snowy mountain wilderness.” Encouraged by Settembrini, he buys skis and under the critical eye of his Italian mentor, he practices with them behind the Berghof out of sight of the authorities who forbid strenuous exercise. He revels in his new skills, finds deep solitude in the beautiful mountains that rise up around him—“not hostile, but simply indifferent and deadly.” He gains courage, feels sympathy with the elements that awaken in him a “devout awe,” that give him “a suitable arena where he [can] resolve his tangle of ideas” imposed by Settembrini and Naphta who, in his words, “scuffle pedagogically for my poor soul, like God and the Devil struggling over a man in the Middle Ages.” Now he’s ready to venture much further into the wilderness.

He poles away from Settembrini, vanishes into white darkness ignoring the pedagog’s cupped-hands-warning of danger. Ever higher he goes, pushing his way toward “a misty nothing,” sometimes stopping to thrust his ski pole into the snow and watch the greenish- blue light jump from the deep hole as he pulls the ski out. The light and color of this “optical phenomenon” remind him of the eyes of the school boy Pribislav Hippe with whom he once was deeply infatuated and of Clavdia Chauchat with whom he is still in love. He skis on. Suddenly he’s racing downward, then up again, then down into “fogged-in forests,” that jut wedge-like into open ground. He stops to smoke a cigarette, feels oppressed by the silence and dangerous solitude. But he’s “proud of having conquered it,” feels “a courage that came from his intrinsic right to such surroundings.” He pushes on “delighted by this freedom to roam, by his own winged independence.”

He presses “ever deeper into the wild silence, into this uncanny world that [bodes] no good.” Fear grows in him. He realizes that he has “secretly, and more or less purposefully, been trying to lose his bearings all this time….” Fear oppresses him. A snowstorm is threatening. Prudence cries, head back! “Oh, so what! I’ll chance it!” Thus he defies prudence, even repudiates it, and “[plunges] ahead in his long wooden slippers.”

What is this defiance, what is this repudiation but something close to the “contempt” Zarathustra expresses in Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra: “What is the greatest experience you can have?” Zarathustra asks his listeners in the marketplace and answers his own question. “It is the hour of the great contempt. The hour in which your happiness, too, arouses your disgust, and even your reason and your virtue.”

I see a very fine line between Hans Castorp’s defiance and Zarathustra’s disgust. As daring skier, Hans has repudiated the Berghof whose reasonable rules are designed to protect him and try to cure him. He has defied his own common sense. Even the narrator calls him “the crazy fellow” for pushing on. But push on he does into a blinding snowstorm. He’s battered by terrific flurries; feels “fear, rage, disdain”; gets lost; suffers exhaustion. ‘[A] merciful self-narcosis’ almost overcomes him, but ‘my stormily pounding heart does not intend to lie down and be covered by stupid, precise crystallometry.’ He skis around in circles, back to the hut he passed earlier, rests there, thinks he can stand there all night if he has to by changing leg positions.

At this hut begins the climax of a long adventure that started with Hans on his balcony enchanted by the magic Alps. Standing in the freezing cold, he dreams of being at a Mediterranean beach where he’s never been before. The day is sunny, the sea blue, the area idyllic. It thrives with youth and beauty and all kinds of lovely people—all described by the narrator in elaborate detail. Then a boy points to a towering temple behind Hans. Hans trudges up the steps, goes inside and sees “two half-naked old women …dismembering a child,” devouring it “piece by piece.” He wakes up in the snow relieved to be rid of the awful women. Of the dream he says, “I knew all along that I was making it up myself.” He gets up, checks his watch, is amazed to find he’s been gone only a half hour. After a lengthy meditation on life and death and love, he sees clearing weather and manages to ski safely back to the Berghof.

In his meditation Hans states the essence of his epiphany:

"Man is the master of contradictions, they occur through him, and so he is more noble than they. More noble than death, too noble for it—that is the freedom of his mind. More noble than life, too noble for it—that is the devotion of his heart….Love stands opposed to death—it alone, and not reason, is stronger than death. Only love, and not reason, yields kind thoughts….I will keep faith with death in my heart, but I will clearly remember that if faithfulness to death and what is past rules our thoughts and deeds, that leads only to wickedness, dark lust, and hatred of humankind. For the sake of goodness and love, man shall grant death no dominion over his thoughts."(487, italics Mann’s)

Hans Castorp and Bud Suttree gain knowledge and insight in a mountain area. At one point Hans stops to study some crystal snowflakes. He sees that no two are alike, the result of nature’s “endless delight in invention, in the subtlest variation and embellishment of one basic design: the equilateral, equiangular hexagon. And yet absolute symmetry and icy regularity characterized each item of cold inventory.” Curiously, Hans and the narrator find this absolute form “eerie…anti-organic….Life shuddered at such perfect precision, regarded it as something deadly, as the secret of death itself.” Similarly, in his October visit to the Smoky Mountains, Bud is “surprised to find small flowers still.” He studies “the delicate loomwork in the moss,” “lichens fiery green,” “scalloped fungus” on rotted logs, “pale indianpipes in pulpy clusters among the debris of humus and rich decay and mushrooms with serrate and membraneous soffits.” He breaks a mushroom in his hands, has forgotten he’s hungry. These little nature studies of Hans and Bud end with thoughts of death. However, unlike Hans’s snowflakes, Bud’s mushrooms are neither eerie nor hostile to life unless they're poison. Bud wonders if “you eat the mushrooms, would you die, do you care.” (285)

Bud’s attitude toward the mushrooms suggests that he’s still fragmented, still in his psychic valley of despond. Yet there are signs in the mountains that he’s dealing with his condition, suffering, working through it. He has visions: an “elfish apparition,” “mauve monks in cobwebbed cowls and sandals,” “old spectral revenants armed with rusted tools of war colliding parallactically upon each other like figures from a mass grave.” Sitting on a gravel bar near icy water and “a green and reeling wall of laurel,” he crosses his wrists in his lap and looks “at a world of incredible loveliness.” The rest of this epiphany is best illustrated in McCarthy’s past tense narration:

"Old distaff Celt’s blood in some back chamber of his brain moved him to discourse with the birches, with the oaks. A cool green fire kept breaking in the woods and he could hear the footsteps of the dead. Everything had fallen from him. He scarce could tell where his being ended or the world began nor did he care." (286)

This revelation is soon followed by another one. Bud sees and hears a wild, hellish carnival of laughter and screams and “foul oaths” and all kinds of weird creatures and bizarre things, including “a gross and blueblack foetus” (perhaps symbolic of Bud’s twin who died in childbirth). These visions enable Bud to see “with a madman’s clarity the perishability of his flesh.” Still, his other self, “[s]ome doublegoer, some othersuttree,” eludes him and he fears that should he join that figure “in this obscure wood he’d be neither mended nor made whole but rather set mindless to dodder drooling with his ghostly clone from sun to sun across a hostile hemisphere forever.” (287)

It will take other epiphanies for Bud to get spiritually whole. I need only mention them: the experience with Mother She helps him see “with perfect clarity” a number of important things in his youth involving life and death and pain. These visions conclude with a fantastic one of the future killing of Tarzan Quinn (427-430). And then there are the profound revelations and visions in Bud’s typhoid delirium, this section of the novel a complex mix of Knoxville hospital treatment and Bud’s spiritual insights. One of the most important he reveals to a nurse: “I have a thing to tell you. I know all souls are one and all souls lonely. (459)

Hans Castorp and Bud Suttree are upper middle class, educated, get funds from relatives, lose family members and friends to death, gain insight through dreams, exile themselves, experience violence, suffer and are cured of diseases, see death up close. I don’t want to make too much of these similarities. Hans is a graduate engineer. We never learn what university Bud attended (probably the Univ. of Tennessee.), what he majored in, or whether he graduated. Hans is an orphan, raised by his great-uncle, and gets a substantial inheritance that enables him to reside seven years at the sanatorium. Mostly a fisherman, Bud goes stretches without hitting a lick of work: a short one after he receives a small inheritance from the estate of a dead relative, a long one when his whore funds him. Hans loses his beloved cousin to disease and another friend to suicide. He tries to stop a senseless duel between two of his “mentors” whose extreme ideas he’s come to see as absurd. Ironically, well-intentioned Hans contributes to this situation that ends disastrously. Bud is haunted by the fate of his twin. He tries to save his black friend Ab Jones from the police but loses Ab to the murderous tactics of Tarzan Quinn.

Hans and Bud are drinkers, drifters, dreamers. Hans drinks to excess on occasion. Bud is alcoholic through much of the novel. Hans and other patients at the Berghof often engage in aimless diversions. In the chapter “The Great Stupor,” for example, Hans “[plays] solitaire everywhere, at any time of day—at night under the stars, in the morning in his pajamas, at meals, even in his dreams.” At times Bud wanders aimlessly around downtown Knoxville. Hans gradually cuts all ties with his past and hometown, makes the final break when his great uncle dies. Bud is a self-chosen outcast from the start.

Love! Hans has a great capacity for it, but his shy nature and the qualities of his romantic interest, Frau Chauchat, abort their relationship. While his boyhood fascination with a school peer may suggest incipient homosexuality, his adult affections for male friends are clearly platonic. His romanticism and rational scruples, his meditations on love and death, his ability to “play king”—all these enable Hans to achieve a Nietzschean “triumph over self,” a new sense of transcendent love.

Love for a female—if this is what Bud Suttree finally feels for the girl-woman Wanda—plays a small part in his psychological odyssey. Much more significant are his complex feelings for his dead twin; his rejection of a ragpicker’s nihilism; his personal suffering, visions and insights, an important one of which is “A man is all men.”( 422) All these experiences result in a new self at novel’s end, one that Bud and the narrator see as a healthy self love: “he’d taken for talisman the simple human heart within him.”(468) This “simple human heart” is blessed by grace in the form of a waterboy, Bud’s new spiritual twin, and a motorist who gives Bud a ride out of town and helps him “fly” all the death-in-life demons that Knoxville, the huntsman and hounds represent. (470-1)

The Magic Mountain is tragic. Europe with all its art and beauty, all its science and sophistication, all its philosophy and inspiring traditions nevertheless ossifies into rigid cultures that clash and finally erupt in war. Within this evolving tragedy Mann creates high comedy with sly parodies of 18th and 19th century narrative techniques, gentle pokes at the naiveté of his maturing “hero” and of cousin Joachim, amusing exposes of Berghof foibles. The novel is a marvel of organic development. All the characters and episodes in the little world of the sanatorium are magnetized toward the Great War. The chapter “The Great Petulance” contains passages that remind me of the divisiveness that has plagued the United States since the 1960’s. Here Mann's narrator describes the mood of the Berghof before the start of the war:

“What was in the air? A love of quarrels. Acute petulance. Nameless impatience. A universal penchant for nasty verbal exchanges and outbursts of rage, even for fisticuffs. Every day fierce arguments, out-of-control shouting-matches would erupt between individuals and among entire groups; but the distinguishing mark was that bystanders, instead of being disgusted by those caught up in it or trying to intervene, found their sympathies aroused and abandoned themselves emotionally to the frenzy. They turned pale and quivered. Eyes flashed insults, mouths wrenched with passion. They envied the active participants their right to shout. An aching lust to join them tormented both body and soul, and whoever lacked the strength to flee to solitude was drawn into the vortex, beyond all help.”(673)

In “The Thunderbolt,” the last chapter, the Berghof is like “an anthill in panic” as the residents, most still sick, go “tumbling head over heels all five thousand feet down to the flatlands and its ordeal…storming the little train, thronging its running boards—if need be, even without their luggage.” The last four pages show Mann the equal of Remarque and Hemingway in describing the horror of a modern battlefield. Stumbling into the hell of machine guns and artillery shells, singing part of a song about a tree on which are carved “[s]o many words of love,” Hans Castorp symbolizes the patriotism and romanticism, especially the German varieties, that plunged Europe into the blood and mire of World War I. On a deeper level Mann prepares us for his hero’s battlefield song in the earlier chapter “The Fullness of Harmony” where Hans is enchanted by a recording of Schubert’s lovely “Lindenbaum” (linden tree). The song arouses in Hans feelings of love and death and most importantly a sense of transcending these contradictions and overcoming self. Here’s Mann’s narration:

“It was truly worth dying for, this song of enchantment. But he who died for it was no longer really dying for this song and was a hero only because ultimately he died for something new—for the new word of love and for the future in his heart.” (643)

Earlier the Nietzschean spirit thrives in Hans Castorp’s full realization of what the “Lindenbaum” means to him. But here on the battlefield he is caught between the clash of massive contradictions to which he is contributing and which will likely kill him. Here the Nietzsche that Mann has put in Hans “uses what tatters of breath he has left to sing to himself” only four shaky lines of the song and then “in the tumult, in the rain, in the dusk, [Hans] disappears from sight.” Bidding farewell to his hero, the narrator/Mann takes the Nietzschean ideal as far as he can take it under the terrible circumstances, but that isn’t very far. What we have in the last three lines of the story is Mann's slim hope for a better world:

“And out of this worldwide festival of death, this ugly rutting fever that inflames the rainy evening sky all around—will love someday rise up out of this, too?” (706)

Suttree is a comedy in the sense that it ends somewhat happily. Bud gets a complete self, though a lonely one; comes to terms with his dead twin; symbolically gains a new one (waterboy); and escapes Knoxville. Unlike Mann’s sophisticated comedy of manners, McCarthy’s Tennessee type rocks with raw, earthy, crazy frontier hilarity: Suttree’s friend Harrogate screwing watermelons, sewer-rat Harrogate trying to blow into a bank only to explode himself back in a deluge of shit, the river baptism Bud witnesses, and other amusing instances.

Comedy, however, is a distant second to this novel’s gloom. Its self-centeredness, its sadness-violence-doom all add up to a powerful story of high pathos. To me the ending seems overly contrived, as I argued in a previous McCarthy Forum thread. Mann ends much more convincingly than McCarthy. He controls his Nietzsche and allegory beautifully and doesn’t let either upstage the realism of a now anonymous soldier “dazed” and “thoughtless” (Mann’s words) singing to himself as he pushes on to almost certain death—a personal tragedy in itself. In contrast, McCarthy overloads Bud’s situation with symbols of grace and medieval soul-devouring (huntsman and hounds) which seem to me quite Catholic and reactionary Catholic at that. I can’t help thinking that McCarthy took Francis Thompson’s “Hound of Heaven,” one of the poems in the lit book we used to read at Knoxville Catholic High, and reversed the heavenly image to his huntsman-hell hounds that are hot after Bud as he leaves Knoxville.

I certainly don’t fault McCarthy for debunking Catholicism and then using parts of it to suit his purpose. After all, artists are free to choose what they like from a system of thought, reject the rest, or use what they like and dislike separately or in combination. Some fail at it, some succeed. McCarthy doesn’t fail with his ending, but he’s heavy-handed about it (an opinion I defended in a previous McCarthy Forum thread.) He’s capable of better endings as he will show in his later novels and in the play The Sunset Limited.

I come to the end of Suttree. I reread it, I study parts of it over and over, and I still wonder how much you’ve really changed, Bud. Sure, you’ve had incisive dreams and visions and your narrator-creator has built a hell for you to bum around in and escape. You leave behind friends who care a lot about you. How much do you really care for them? I wonder if you really mean it when you tell Trippin Through the Dew, your black friend, you’ll return “sometime maybe” then weakly agree to write him a postcard. (468) I’m tempted to ask you where you’re going, if you’ll find things all that different in whatever territory you’re lighting out to. If it’s the West, no doubt more wide-open spaces and cleaner waters. But stick around there a while and things won’t be so open or clean or nice. Those Texas wells will pump more and more bloody “black gold”—ah the oil business, now there’s a “benign” industry for you (I knew it first hand and it’s worse now than when I worked in it). And the western drug business, especially along the Tex-Mex border, will bring loads of misery and murder that will make Tarzan Quinn and his cop cronies seem almost nice by comparison.

Well, the story’s over and you’re free as the west wind, Bud—for now anyway.

* McCarthy’s Tarzan Quinn is based on a real person, Lester Woodrow (Tarzan) Gwinn. At my request, McCarthy scholar Wes Morgan of the University of Tennessee sent me details on Gwinn which Morgan sometime ago had gleaned from Knoxville newspaper articles of 1955. Here are excerpts from Morgan’s report: ...Gwinn was a large man standing 6 ft.-3 1/2 inches tall and weighing some 280 pounds. He had been a local Golden Gloves heavyweight boxing champion and an amateur and professional wrestler earlier in his career. During the Second World War he had earned the Silver Star, the Oak Leaf Cluster, as well as the Purple Heart, Good Conduct and marksmanship medals while serving as a sniper in the Pacific. Gwinn joined the Knoxville Police Department on July 9, 1949. On August 13, 1952, Gwinn was suspended for allegedly taking $40 in what became known as the “whisky bribe case.” He was later reinstated. As a police officer he was known to be particularly tough on drunk “repeaters” and “shady characters” who made trouble on his beats. Some who remembered him described him as a sadist.

He had another side to his personality as well. He grew flowers and operated a seller’s truck on Market Square during flower season where he habitually gave away the flowers that did not sell on a particular day. He was well known for his youth work and worked as a counselor at the FOP boys’ camp. He and his wife Rose adopted a son, Harlas, after the child’s father was made an invalid in an accident and could no longer care for the child. The Knoxville Journal also printed a brief account of officer Gwinn carrying a drunk found lying in the street about 50 or 75 yards out of the subfreezing weather to the warmth of his cruiser….

Gwinn was killed in the line of duty as a police officer on January 31, 1955. He was 40 years old....McCarthy seems to have gotten things a little mixed-up in his recounting. Officer Gwinn was killed by Roy Porter at the home of Robert Van Winkle, not by Little Robert.

At the time,

Robert Van Winkle was a hillbilly entertainer and musician who went by the name “Little Robert” ....In addition, Little Robert was best known as a guitar picker, not a fiddler as McCarthy would have us believe....Quinn was the maiden name of his [McCarthy's] paternal grandmother. A coincidence?

Mann, Thomas. The Magic Mountain. Trans. John E. Woods. Alfred A. Knopf, 1999. According to most Mann scholars today, this translation is superior to the first English translation of 1927.

McCarthy, Cormac. Suttree. Vintage Books paperback, 1979.

_______________. Blood Meridian. Vintage Books paperback, 1985.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. Thus Spoke Zarathustra. Trans. Walter Kaufmann. Penguin Books, 1976.

Unfortunately, McCarthy was again passed over for the Nobel Prize, which in 2010 went to

Peruvian writer Mario Vargas Llosa.

One wonders what chance McCarthy will ever have when the American nod in recent years has been going to, arguably, lesser writers. Even if he were to be nominated, he would have a hard time winning because of the strong Eurocentric nature of the Nobel Prize. It certainly doesn’t help any American nominee’s chances when his or her country is branded literarily inferior to Europe. According to Horace Engdahl, the 2008 secretary of the Nobel Academy, "There is powerful literature in all big cultures, but you can't get away from the fact that Europe still is the centre of the literary world ... not the United States," he told the Associated Press. "The U.S. is too isolated, too insular. They don't translate enough and don't really participate in the big dialogue of literature ...That ignorance is restraining." However, Peter Englund, Engdaul’s 2009 replacement, sees Eurocentrism as “a problem” and has taken a better view of American literature and its Nobel potential.

Though Engdahl’s criticism grates on my American ears, I believe there is considerable truth in it. With all our educational opportunities and multicultural advantages, we are pretty insular and seem to be getting more so. Our news is more and more local. Our media sensationalizes sleaze and violence and serves up too much celebrity fluff. I often have to turn to the BBC to get some idea of important developments in other parts of the world. Few of us know any language other than English, and many of us lack sufficient fluency in it. Sloppy, lazy usage is epidemic, even among journalists and professional writers who should know better. As Engdahl and other critics have observed, our art is much too concerned with mass trends in our culture. American literature has narrowed in focus and scope. Most of our writers are not wrestling with the big issues

A major exception is the work of Cormac McCarthy. At his most lyrical and transcendent, McCarthy is the equal of his influencer Faulkner; in dialogue and dialect he surpasses Faulkner. As a minimalist novel, McCarthy's The Road is better than most in the genre and, I believe, as good as Nobel winner J. M. Coetzee's best. McCarthy’s most profound work—and there is much of it—speaks for itself and should alert any Nobel official that he is a worthy candidate for the Prize.

Still, there are elements in McCarthy that may hurt his chances. His fascination with “pure evil” (his description of the villain Chigurh in No Country for Old Men) and with hellish, almost unrelieved violence gives some of his work a medieval coloring. This emphasis probably stems from his belief (stated publicly) that we are going to destroy the planet well before any scientifically estimated end time. This may happen, but art should not despair to the point of offering little to no hope for the human condition. Interestingly, some devotees have called The Road, a post-apocalypic novel, McCarthy’s most hopeful work and I agree. He has been rightly criticized for having few important women characters. When Oprah asked him about this lack, he said that he found women “mysterious.” This is not surprising. American male writers generally have had a hard time creating memorable women characters. Notable exceptions include Nathaniel Hawthorne's Hester Prynne (The Scarlet Letter), Tennessee Williams' Amanda Wingfield (The Glass Menagerie) and Blanche DuBois (A Streetcar Named Desire), and John Steinbeck's Ma Joad (The Grapes of Wrath).

It may well be that Cormac McCarthy, 77, still very productive and reportedly in excellent health, may yet produce his greatest work and an American epic for the ages. He is currently at work on a novel tentatively entitled The Passenger.

November 17, 2009 Yesterday I finished a class at Oak Hammock at the University of Florida's Institute for Learning in Retirement. Taught by UF Prof. John Van Hook, it dealt with three novels: John Updike’s rabbit, run and Rabbit Is Rich and James Kelman’s Kieron Smith, boy. (this is the second class I’ve taken from Van Hook, the first one on three Southern novels, including McCarthy’s The Road).... In addition to the class assignments I wrote the following argument:

Pro vs. Con on rabbit, run and Brief Mention of Two Other Rabbits

(Editions cited: rabbit, run. Fawcett Books, 1988. Rabbit Is Rich. Borzoi Books, 1981.)

PRO: rabbit, run still reads well after all these years.

CON: Aw, early Updike! Young writer straining to show he can turn a phrase about the American variety of the human condition.

PRO: Well, he still impresses this discerning reader.

CON: How so? Examples please!