|

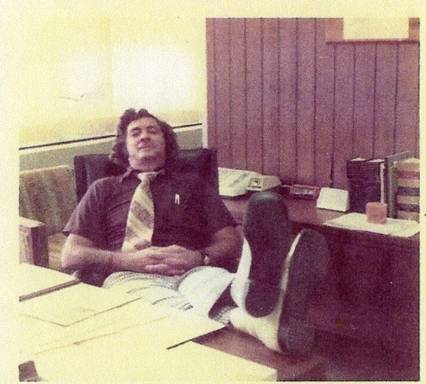

Reginald (Reg) Touchton (1930 - 2011) was my close friend and colleague at Florida State College at Jacksonville. Like me, he first was a mid-level administrator and then a professor who chose to return to the classroom. He developed an outstanding college developmental education program for which he received national recognition. Ever the fun-lover, Reg acted out jests to the delight of friends and colleagues, like this pose in his office at North Campus (ca. 1973.) While on Army leave in Japan, he got a tatoo on his right arm. He liked to twist the skin to show the ship "sailing."

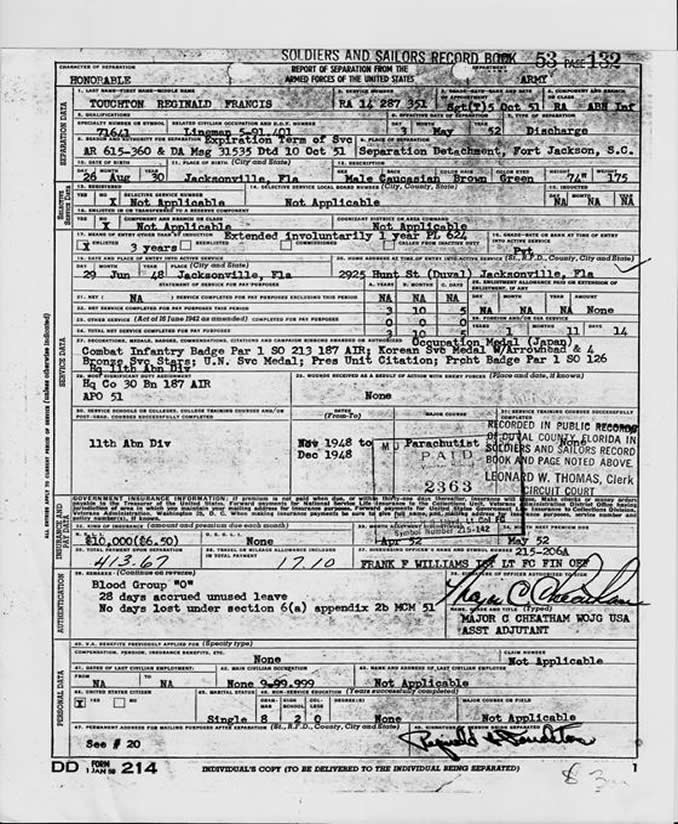

Reg had intended to give me a story about his combat experiences, but his years of severe Parkinson's Disease prevented that. He was a decorated veteran of the Korean War and had previously served in the Army of Occupation in Japan. After his parachute drops into war zones, he would lay down communication wire--a very dangerous job. Once I asked him if parachuting got easier after the first jump. "Every jump I made was as scary as the first one," he said. Carrie, his widow and loving wife of many years, gave me the following copies of Reg's service record and his unit's commendation letter:

Alvin Warnick is a founding member of Oak Hammock at the University of Florida and a retired UF Professor of Animal Science. For his friendly nature and dedication to the community he has been given the honorary title, "Mayor of Oak Hammock." A widower, Alvin is the father of two daughters and a son. He has seven grandchildren and seven great grandchildren. For 2 ½ years during World War II, he served overseas in the Eighth Air Force

On December 7, 1941, I was in Chicago as a guest of Swift & Company, the meat-packing firm. I was one of 30 land-grant students, including E. T. York [former Chancellor Emeritus of the University System of Florida, now deceased]. We students got to Chicago because the company liked our essays on meat-packing. I was there three days, December 5 – 8, 1941. I’d never even heard of Pearl Harbor. Like everybody else, I was upset about the Japanese attack. I realized it was war for the U.S. and I’d be involved. In June of ’42 I graduated from Utah State University with a degree in Animal Science. Before I graduated, I had a scholarship to the University of Wisconsin.

I was trying to earn money for graduate school and started working for the Army Corps of Engineers on the camp project to relocate Japanese. They had been living on the West Coast. My job was checking in lumber and building materials shipped in from the Northwest. The materials came into Delta, Utah, by rail. After they were checked in, they were hauled to the relocation camp in the Topaz Mountains about 15-20 miles away.

What were local attitudes toward the camp and about Japanese Americans being forcibly removed from their homes?

At first the local community was apprehensive about the camp. There was some feeling of it being unfair, but of course this was wartime and we were all very upset at the Japanese and Hitler. I left before the camp was finished, before the Japanese came in. I did some checking recently when I went back to Utah. According to my nephew, his father (my older brother now deceased) told him that many of the Japanese were well-to-do people. The camp consisted of barracks in close quarters and was weather-proofed. The Japanese were able to circulate in the area and go shopping in Delta. The local people didn’t seem to be worried about them. The camp helped the local economy. The Japanese were very industrious people. They improved the outside of the camp with gardens and flowers. However, I’m sure they were upset at being forced to live there. I don’t know whether they were supervised when they went out in the community.

On September 4, 1942, I volunteered for induction. Most of us were anxious to be involved in the war. We went in the service to do a job and get it over with. Some misrepresented their age to get in. I scored high enough on the test at the Fort Douglas Induction Center to be assigned to the Army Air Corps at Traux Field near Madison, Wisconsin. My hearing wasn’t good enough for radio operator and I became a radio mechanic. We repaired communication equipment in the radio school. It wasn’t long before I was shipped to radar school in Boca Raton, Florida. We learned how to operate and repair IFF radar equipment [Identification Friend or Foe]. We were sent from Boca Raton to Atlantic City where we got basic infantry and overseas training.

I think we realized the dangers of war. If I go overseas, will I ever come back or not! But I started looking forward to the adventure. I really wasn’t that worried. I felt God was watching over me. I have always been a practicing Mormon. I prayed each day as if I was at home. I take a little book of Mormon with me at all times. Young Mormons have the opportunity to get a patriarchal blessing. That blessing states your lineage and blesses your potential. The blessing says if I’m called to military service, serve willingly, and keep all the Mormon Commandments that I will be protected. That blessing and my faith gave me a good feeling of security to meet whatever challenges I had to face.

When I was stationed at Traux Field I used the occasion to meet three professors I expected to have at the University of Wisconsin when I got out of the Army. Each one was very nice and invited me into his home. Professor Bohstedt was Chairman of Animal Science then. He told me, “Alvin, your assistantship will be waiting on you when you get back.” I had every confidence that I would come back and would study under those professors.

In April of ’43 our group that had trained at Atlantic City sailed from New York to Liverpool, England, on the USS Mariposa. The trip took 9 days. We were trying to dodge German U-boats. We took a tortuous route, went south then north. Fortunately we didn’t run into any U-boats. We were assigned to the 8th Air Force and sent to radar school in South Kensington, England. We lived in a Red Cross facility near the school. I was very impressed with the RAF students. The British were kind, very helpful, and their instruction was very good. On weekends, the British showed us sites in London and along the Thames River.

From the radar school we were assigned to the 100th Bomb Group located near the town of Diss in East Anglia. We were assigned to barracks according to our job. We worked in a shop. At first there were only four of us radar mechanics, one per squadron. By war’s end there were 90 radar mechanics. Our job was routine repairing and training of navigators to use the GEE Box for short-range navigation, 300-500 miles. We never flew. Our job was to teach, install and repair the equipment in the B-17 bombers. Here's a picture of me standing by a B-17. All the planes had special names. This one was named Our Gal Sunday. Swastikas on a plane indicate enemy planes the crew shot down.

We became close to the people we worked with: the mechanics, navigators, and radiomen. We didn’t have much contact with the pilots. I’m sure the pilots had fears. In some of the early missions 30 planes, each with 10 men, would be sent out; only 20 returned. Each pilot had to fly 25 missions. They were looking forward to finishing their missions and getting out of harm’s way. They ranged in age from 19 to 25. Some were no more than 19 or 20. Flying a B-17 was dangerous work and took quite a bit of courage and daring. The young pilots tended to be more daring.

On D-Day we didn’t lose a plane. Some of our crews flew three missions on D-Day. They’d fly over drop their bombs, come back, and fly another mission. By 1944 the Germans were running out of steam. I have a friend named Robin Baxter. Robin’s father was Rudolf Baxter who came here after the war. Rudolf was drafted into the German Army and flew a Messerschmitt night fighter. Rudolf said the last five or six months of the war the Germans had planes but no fuel. He died a couple of years ago.

How much evidence of the war’s destruction did you see?

I saw planes coming in badly shot up. Some came back with only one engine working. It was a miracle they could fly at all. The worst thing I saw was a plane with a hole three or four feet in diameter. All that was left of the radio operator was blood and body parts. One morning we were out on the flight line and heard the red alert. We ran to a ditch. A German plane was aiming for the runway but his bomb hit off to the side. Our planes were still able to take off.

Toward the end of the war, the Germans started launching “buzz bombs” toward London. The buzz bombs were unmanned missiles the Germans launched from Holland. I never saw any buzz bombs, but I sure heard them. They made a hideous noise. As long as you could hear them, you knew the bombs were on their way to someplace else. Our shelters were made of concrete and brick, but we didn’t use them much.

I was in the Army over three years. I still have my uniform and it's in good shape. I made Tech Sergeant and got the ETO medal [European Theatre of Operations] and the Good Conduct Medal.

Tech Sergeant Alvin Warnick in England, January 1945

I assume you married after you got out of the Army.

Yes. I married Barbara Webster on August 20, 1947. We had a happy marriage of 56 years. Barbara got her master’s degree in Human Genetics and became a Teaching Assistant at the University of Wisconsin. She was active in the Ag Women’s Club at the University of Florida and served as its president. She died of lymphoma in 2003.

Wilse (Bernie) Webb is a retired Professor of Psychology. He held professorships at the University of Tennessee and Washington University in St. Louis, headed the Aviation Psychology Laboratory in the Navy School of Aviation Medicine, chaired the Department of Psychology at the University of Florida (UF), headed the development of a psychology laboratory and a graduate program at UF, and was honored as Distinguished Research Professor at UF. His many publications include Biological Rhythms, Sleep and Performance and Sleep, the Gentle Tyrant. Mary, his wife of 65 years, died in 2007. He has three daughters, one son, eight grandchildren and two great grandchildren, all of whom live in Florida.

On February 16, 2010, I interviewed Bernie in Oak Hammock’s Meditation Room. He talked about some of his experiences during World War II.

World War II actually made the United States. Before that we were in the Great Depression. By the time the war started, we had not recovered from it. My father had lost his lumber yard in Yazoo City, my hometown. I was a student at LSU barely scraping by on $35 a month. My mother was the springboard of my life, a dynamo and a grande dame. She got a job in Roosevelt’s CCC program [Civilian Conservation Corps]. Eventually she headed this program in Yazoo City.

The war created us in the sense that it got us out of the Depression. It took us out of our hometowns. We rubbed shoulders with people from every walk of life. The war put women in the work force, gave impetus to new opportunities for minorities. Rosie the Riveters brought home paychecks; family incomes greatly increased. The United States didn't suffer as badly as other countries.

Serving in Aviation Psychology, U. S. Army Air Corps

I had a wonderful war. When it began, I was playing bridge in a frat house at the University of Iowa, where I was a graduate student in psychology. My college major was the reason I had a wonderful war. Two years before the war, John Flanagan had started the Aviation Classification Program for the Army Air Corps. Flanagan was an expert in applied psychology and the Army made him a colonel. When the war broke out, Flanagan sent letters to all the psychology departments to get people to work in the Aviation Classification Centers. I was one of them. In fact, about a third of my class enlisted in this aviation psychology program.

Our job was to test prospective pilots, navigators and bombardiers to see if they were trainable or not trainable. We tested their motor skills, math abilities, emotions, and other qualities they’d need to function in combat. When you put a person in a bomber or fighter plane, you better have the right man for the job. We tested 100 men a week. There were three Aviation Classification Centers: one at San Antonio, Texas; one in Nashville, TN; and one in California.

This was a marvelous program. I was promoted to Master Sergeant. But after eight months in the program, I saw that the war was not what I expected. My father had served in combat artillery in World War I. I wanted the kind of challenge he had. So I applied to Officer Candidate School hoping to get in the artillery. I was commissioned but they sent me to Adjutant General School. This was not what I expected either. Eventually I was sent back to the Aviation Classification Center in Nashville and became a member of Flanagan’s staff.

Flanagan assigned officers to collect data on people who passed or failed in the flight training programs. Our job was to find the successes and failures at every level of training. I got involved in evaluating how accurate fighter pilots were in shooting at tow targets. A plane would tow a target across the sky and a fighter pilot would shoot at it with colored bullets. One fighter used red-colored bullets, another green-colored, etc. They’d fire at the targets. The targets would drop to the ground. My job was to read the targets and see which pilots excelled and which ones didn’t. I sent the information back to the Classification Center. This exercise really didn’t help the pilots that much. There was always a delay in their finding out how they did. These pilots were flying the fastest trainer planes we had. They were being prepared to fly P-47 fighter planes.

I found out our P-47 pilots were going to Okinawa. I went to Flanagan and asked for TDY [temporary duty] to Okinawa. On the way over, our troop ship almost got hit by a Kamikaze suicide plane. I was stationed at Ie Shima, a small island two or three miles from Okinawa. Ie Shima had been taken, but there was still scattered resistance from the Japanese. About three days before I got to Ie Shima, Ernie Pyle [war correspondent for Scripps Howard newspapers] was killed there. It was very sad. The GI’s loved him. The nearest thing we came to danger on Ie Shima was from Japanese planes. They interrupted many of our evenings trying to bomb our air strip. Another danger was falling debris from the shells our ships were shooting at the enemy on Okinawa. What goes up must come down. You can’t fight a perfect war.

Major Problems in P-47 Missions Against Kyushu

Our P-47’s would take off from Ie Shima and fly 500 miles to attack Kyushu, the southern-most island of Japan. The P-47 was effective in air combat and particularly good at ground attack. Fully loaded, it weighed up to eight tons. That’s why it was called the “jug.” It was a very strong plane. We heard that one guy in Europe banged into a mountain with the thing and was still able to fly it back to base. The main complaint about it in Europe was it was a very heavy, slow climber.

For missions against Kyushu the P-47 was the worst plane for the job. We lost ten P-47’s at Ie Shima. The runway was short, about 3 miles long, often soggy. The planes couldn’t get up enough speed to get off the runway. If they weren’t going at a safe speed and didn’t brake two-thirds of the way down the runway, there was disaster. Another major problem was that P-47 pilots didn’t have any intensive training in navigation. They navigated by eye. They had to fly 500 miles to Kyushu, fire their rockets, drop their bombs, and fly back. This flying was particularly perilous at night. We lost a dozen planes that couldn’t find their way back.

P-47 missions against Kyushu were useless. Our B-29 bombers had already wiped out many Japanese towns. It became apparent the P-47’s were being built up for the invasion of Japan. We all knew this invasion was in the works. Without the atom bomb, P-47’s would have had a major role in attacking troops and positions on the Japanese mainland.

Earlier you mentioned flying over Kyushu during the fighting. Would you give some details about that?

We were using B-25 bombers for navigation, as lead planes for the P-47’s in their attacks on Kyushu. I admired the combat pilots immensely and wanted to be like them. I wanted to test myself. I asked a B-25 pilot if I could fly with him and his crew as an observer on the Kyushu missions. He said, “Hell yes!” (Laughs) We circled at 8,000 feet over Kyushu. I watched as the P-47’s dropped bombs and fired rockets at Japanese positions. I went on three such missions.

Okinawa was bloody and nasty. The Japanese were ordered to fight to the death. It was a rare thing for Japanese to surrender. I do recall a few poor, bedraggled ones swimming from Okinawa over to our island. They were desperate to surrender to us. Our unit on Ie Shima had no guns to guard them. We were completely unarmed. We had to borrow guns from the only personnel who had them: pilots and MP’s (Laughs)

Everybody in the military then knew we were saved by the atom bomb. We felt good times were coming. I am most grateful for my four years of service in World War II. They were my formative years. I matured, advanced to First Lieutenant. By the time I got out of the Army, I had found my mission in life in the field of psychology. While I saw little brutality up close, I had friends in Mississippi who did. “Wild Bill” Hagman and Joe Curran volunteered to be aviators. Wild Bill was basically blind in one eye, but he finagled his way through the entrance test. He got in the Air Corps and bagged two German planes. He and Joe Curran saw some brutal stuff, but it didn’t break them. It made them.

I really believe that many of us who served during World War II were better for the experience.

What led you out of academe into the Aviation Psychology Laboratory in the Navy School of Aviation Medicine?

After the war, I had been plodding along as an assistant professor of psychology, first at the University of Tennessee where my family and I had lived in "apartments" converted from Army barracks and then at Washington University in St. Louis. At U.T. in Knoxvillle my department chairman was Jim Elder who laid a sound foundation, and I am pleased to have been a part of it. But Washington U. offered me more money. I had three kids, increasing responsibilities and need for still more income. Because I had published, made Teacher of the Year and was in my third year at Washington University in St. Louis, I went to the department head and asked to be promoted to associate professor. He said it was a matter for the dean. The dean said this kind of promotion could not be given until after the fourth year. He liked to call Washington U. “the Harvard of the Midwest.” I called some people I had known in the Army and got a referral to the Naval Station at Pensacola. The Navy offered me a GS-12 civilian job at $12,000. I took it. It proved to be valuable experience that helped me in my return to academe.

What were your duties in the Laboratory?

I worked there five years, 1953–1958. Basically, I did the same thing with Navy pilots that I did with Army pilots during the war. Our lab was involved in early astronaut training. Men were being trained to operate complex machines. There was a completely new perspective on space. The question was, How do we measure the effects of space on astronauts? We went to Langley Field where the astronauts were training and presented them with a set of tests to take. All but one said, “Your tests are ridiculous. We’re perfect.” (Laughs) One said to his fellow astronauts, “Aw, c’mon! These fellas are just trying to do their job.” Do you know who that one astronaut was?

John Glenn.

Right! He was a stellar gentleman. Trying to evaluate these astronaut candidates with a battery of tests was like trying to test Army pilots who had come off combat missions. Both groups didn’t have their minds on the tests. The Army pilots were so grateful to be back alive, that’s all they were thinking about. After I left the Navy Laboratory and returned to academe, I did some consulting for the government. Did you see that George Clooney thing The Men Who Stare at Goats?

No, but I read about it. It’s about paranormals in the U. S. Army, isn’t it?

Yes, and it’s bullshit. I got involved in similar mess with the government. They had stolen a sleep machine from Russia. I was called in to evaluate it. I tested it and found it was worthless. (Laughs)

Bernie Webb’s military decorations: Okinawa Campaign Ribbon, Pacific Theatre Medal, World War II Victory Medal, Good Conduct Medal.

Brandon Mayhew Wight (Brandy) has led an exciting, charmed life. He graduated from the Rhode Island School of Design, was a noted dealer in art and antiques, associated with a number of the rich and famous, and was a meritorious soldier and air raid warden during World War II. A resident of Martha's Vineyard for many years, Brandy is related on his father's side to the Mayhews. Thomas Mayhew was given Martha's Vineyard by the King of England, was the first governor of this island, and was among the first white settlers on Martha's Vineyard. Brandy traces his roots back to Roger Williams through his mother, Edna Colwell Stockard Wight. On Martha's Vineyard Brandy and his long-time partner Bruce Blackwell established the Granary Gallery at the Red Barn. Their patrons included President Bill Clinton and his family, Jackie Kennedy, and other notables interested in exquisite collectibles. Bruce and Brandy have had a loving relatiionship for 47 years. They married in a rooftop ceremony on Martha's Vineyard in 2004 and in 2006 retired to Oak Hammock at the University of Florida. In late October 2010 I interviewed Brandy about his war experiences. He showed me an album of photos, sketches, and news clippings pertinent to his Army service in the South Pacific. I also asked Brandy and Bruce about some highlights of their proprietorship of the Granary Gallery at the Red Barn.

The covers of this album are parts of a B-29 plane that crashed on Saipan. On Saipan I was the dispatcher in the motor pool and a member of the fire department. I had to make sure the vehicles were ready and they had drivers. A friend in the machine shop made these album covers for me. I was part of an Army Engineer aviation battalion that arrived on Saipan in the spring of 1944, a few days after the Japs had left. The town and airfield had been flattened, completely destroyed. No buildings standing, just ruins, fragments all over! The countryside still looked lush and beautiful. Surprisingly, natives still worked the fields; they lived in huts. Many natives had probably been killed. The ones we saw looked old. I didn't see any young men or women and don't recall any American contact with the natives. We were working day and night.

Our mission was to rebuild the airfield and construct another airfield so B-29's could use them to bomb Japan. Coral made for a very hard surface for planes to land on. Our guys worked long hours constructing the Isely and Kobler Airfields. After a hard day they came in covered with coral dust and looked like ghosts. The B-29's were called Super Fortresses, huge planes, very strong. But I recall several coming in shot up and crashing.

One night Jap Zeroes came in low level in droves. They were like vultures, their gunfire winking and bullets ripping up the ground and tearing into things. They hit a B-29 and it caught fire. I got the fire truck out and we drove over there as fast as we could. We put water on ourselves and splashed it on the plane. Fortunately, the fire hadn't reached the gas tank. We were still under attack; I don't know why they didn't hit us; we were just lucky. This was my closest brush with death.

May I include the citations about your part in this action?

Yes. The first is from Major General Sanderford Jarman:

During an Army raid in the early morning of Dec. 7, 1944, Sergeant Brandon Wight was a member of a firefighting crew assigned to an Engineers aviation battalion that was summoned to extinguish a burning Super-Fortress at Isely Field, Saipan. Despite the distance involved, the crew of which Sergeant Wight was a member was the first to reach the scene. Employing new equipment with which they had not previously had actual experience, Sergeant Wight and the crew immediately attacked the flames by closely approaching the plane in the face of imminent danger from burning aviation gasoline and exploding ammunition. An enemy plane passed directly over the area and dropped additional bombs but Sergeant Wight and the other members of the crew did not cease in their mission. Under these hazardous conditions the fire was extinguished in an extremely short time and other Super-Fortresses were thereby saved from damage. The courage and devotion to duty of Sergeant Wight reflect great credit upon himself and military service.

The other is from Colonel Brendan A. Burns, Commander of Corps of Engineers:

For meritorious achievement in connection with military operations against the Japanese enemy from July 25 to Dec. 31, 1944 on Isle of Saipan.

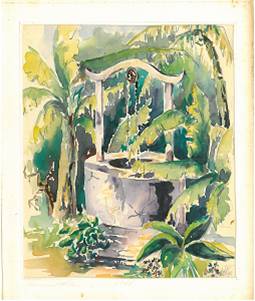

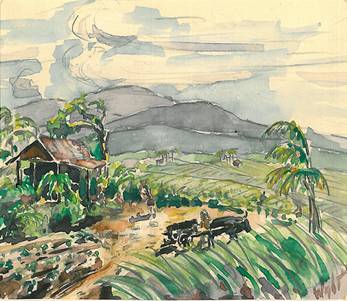

Our unit spent 11 months on Saipan. We lived in pup tents the whole time. Men got bored and number of the guys got island happy. That meant they were despairing, despondent. I was lucky because I had a jeep to use and could occasionally get out to the countryside. I made watercolor sketches of some scenery on Saipan. This first one is of a well. Banana leaves surround it. The next one shows a hut and a native with an ox-drawn cart and figures in the background.

Really vivid. Very well done!

Thank you. It's funny. I thought the Army would use me for what I could do best and was schooled in. I had done interior design work in civilian life and specified camouflage, which I trained in at Ft. Belvoir. But when I got to the combat area, I ended up in the motor pool. (Chuckles)

In early '45 we got orders for Okinawa. Along the way our troop ship went through a typhoon. It's like being in a tornado except a typhoon goes on all day. Everyone got seasick. That was the only time I saw a lot of praying. We ran into another typhoon on our way back to the states. These things are really scary.

You were part of the American invasion of Okinawa, weren't you?

Yes. Our ship joined the mob of ships in the harbor: destroyers, battleships, troop transport carriers, and others. Kamikaze planes plunged into ships causing terrible explosions. Many of our men were killed. Three ships were bombed not far from us. It was a horrible thing to see. When daylight came the Marines went in and fought hard to secure the area. Eventually we went ashore and had the job of repairing and lengthening the Kedena Airfield, which was badly damaged. I had the same job on Okinawa that I had on Saipan.

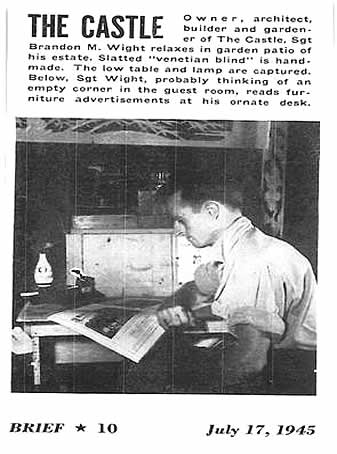

After a while duty on Okinawa began to affect many of the men. They got despondent, bored; these moods became known as going rock happy. Some guys broke the boredom by landscaping and decorating their tents with captured items from the ruined village of Naha. A photographer from the Army magazine Brief visited many creative works, including mine, and captioned photos appeared in an issue of the magazine.

My endeavor was called "The Castle." I had furnished my tent with the remains of a secretary desk, an old stool, many straw mats, bamboo, and, of course, plants.

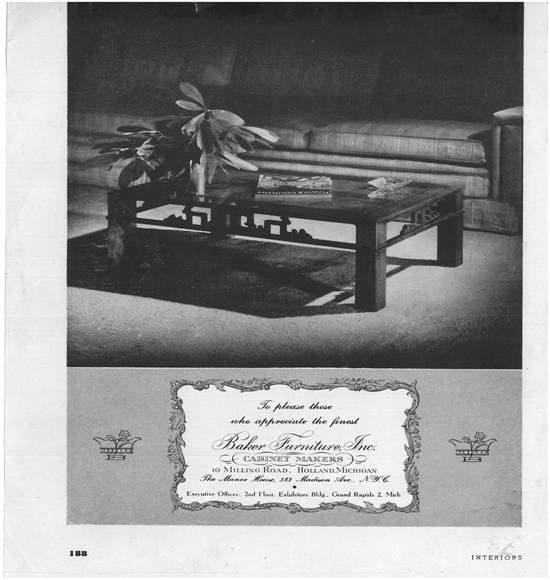

Just outside the tent in the center of the "terrace" was my special treasure, a beautiful sake table that I had discovered in Naha (the table in the magazine article is not the sake table). I was hoping I could ship the sake table back to the states, but impossible! I took photos of it and made a drawing of it with all dimensions and wrote a letter telling where I found it. I sent these materials and the letter to Hollis Baker, President of Baker Furniture. Before Army service I had worked for Mr. Baker in the Madison Avenue New York City Showroom.

Later I received a letter from Mr. Baker saying he liked the table very much and would put it into immediate production. Naturally I was excited, especially when I first saw an ad in Architectural Digest for the Okinawa Table by Baker Furniture.

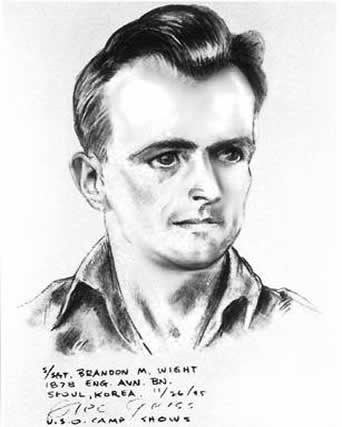

After all these years, this is my best recollection of my tour of duty in the South Pacific (without the music). A balance between the ugliness of war and the pleasure of creative relaxation! After Okinawa my unit went to Korea; I was there several months after the war ended. Here's a picture of me drawn by a USO artist in Korea.

Good. In your story I'll place it next to your Okinawa picture.

I look back now and recall some enjoyable times in the Army. Before Saipan we were stationed at Hickam Field in Hawaii. Hickam had been hit hard during the Pearl Harbor attack, but when we got there it was pretty well fixed up. Since I was in transportation I was in charge of getting the beer during beer call. The troops were a happy lot then. I remember the costume acts. Guys put on grass skirts and danced to Hawaiian music. It was a lot of fun.

Do you recall any friends from your military days?

Oh yes. I first met Ogden Salmon at Ft. Dix. I came into the barracks and heard someone whistling music from The Magic Flute; it was Ogden. Ogden became ill and didn't make it overseas. He and I stayed in close touch through the years. Ted Conway and Ray Sticter and I were together on Saipan, at Okinawa, and in Korea. They were wonderful guys. I remember Ray helping me with my luggage when I left Korea. Ted Conway later got a music degree here at UF.

Bruce is with us now. I would love to hear about some of the highlights of your time at the Granary Gallery at the Red Barn.

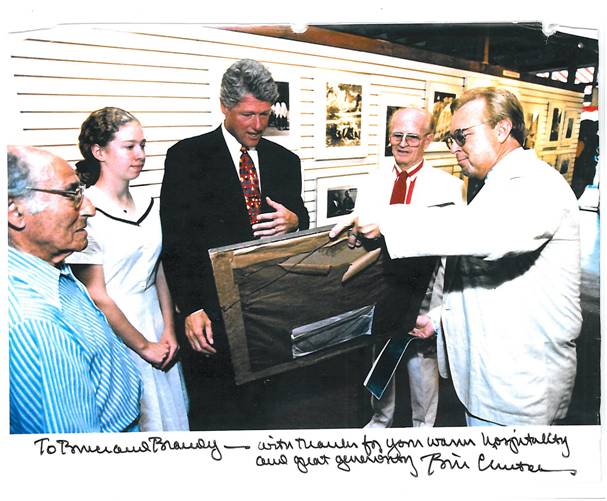

Brandy: One day in August of 1993 Bill Clinton, Hillary and Chelsea came in. We were showing photos by Alfred Eisenstaedt. At the time we were the first gallery outside New York City to show Eisenstaedt's work. President Clinton told us he was greatly interested in history. After Eisenstaedt showed the First Family all his photos, President Clinton explained historical details in some of the photos to Chelsea.

Bruce:. We gave the president an 1800 copy of the Declaration of Independence for the country. Had we sold it, we could have probably retired. The president was thrilled. Here's a picture of us presenting the document to the president. I'm holding it and Brandy, wearing a tie is to my right. At left is Alfred Eisenstaedt. As you can see, Bill Clinton signed our photo at the bottom there.

The following year the president came to Martha's Vineyard and invited us to hear his Saturday Radio Address. The next year, 1995, I wanted to do something special for Brandy's 80th birthday. It took quite a bit of arranging, but we were able to visit the White House on Brandy's birthday, May 19. We met President Clinton, visited the Oval Office, even met Socks, the cat. (Chuckles) The president invited us to his personal living quarters to see the document we had given him two years earlier. And there on the wall of the East Wing was the copy of the Declaration of Independence, our gift to the country.

Brandy: Famous people would come into the Gallery. We made sure they had as much privacy as we could afford, would even close off a room where they were.

Bruce: Jackie Kennedy came in several times. She wore sunglasses and plain clothes, trying not to be conspicuous. One time Jackie was with Rose Styron, the wife of writer William Styron. They wore short tennis dresses and bent over to look at something, completely unaware of what they were showing. I whispered to Brandy what a photo that would make. (Laughs) But we always respected our customers and tried our best to meet their needs.

Brandy: Celebrities got along well with the locals on Martha's Vineyard. There were no social barriers. We met people like Lillian Hellman and John Hersey. They were down to earth, very good to be around. One time my first partner George Bigelow and I were at a party given by Katherine Cornell, the great stage actress. Noel Coward was there. He was delightful, sang and played the piano. I had some discomfort in my back and Noel said he could ease it. He manipulated my shoulders nicely and I felt great relief. After George died, I got a cable of condolence from Noel Coward. He was a truly wonderful fellow.

Bruce (left) and Brandy (age 98) at Gainesville's 2013 festival celebrating Lesbian-Gay-Bisexual-Transgender Pride. This picture is from an Oct. 27 article in The Gainesville Sun, "Pride Festival has extra meaning for longtime gay couple."

For Martha Wroe education and personal independence have been foremost in her life. A clinician and an educator throughout her career, she started the Physical Therapy Program at Shands Hospital at the University of Florida and became chief physical therapist, instructor, and later professor of physical therapy. Here she talks about her medical experiences during World War II.

I came from a family of three brothers and I was the youngest child and my brothers in the service. Everybody was pretty patriotic then. We had a flag in the window with four stars meaning my brothers and I were in military service. One of my brothers, Edmund, was killed in Italy. He was in the infantry, 3rd Army Division. He had a chest wound and might have been saved if they had had medical care then like we have today. I was adventurous and that was one of my motivations for joining the WACs. I thought that was a way of doing my part for the war effort.

I went to Ft. Oglethorpe, Georgia for basic training and that was a culture shock. (Laughs) I had graduated from Western Kentucky with a degree in biology. At Oglethorpe I expected more people with my background, but I really didn't meet that many. Before I knew it I was a platoon leader and terribly inefficient. I would say, "March left!" and I intended them to go right. (Laughs)

What did your basic consist of?

Drilling, learning Army rules and regulations, bed check, things like that. Basic training lasted 6 weeks.

Did you have any weapons training or any orientation about the enemy?

No. I was very interested in the war and was pretty aware of what was happening and why. Most WACs were used in office work. After basic training I went to Ft. Dix, New Jersey, and wrote reports of court martials. Some of the court martials were for desertions. I was there about three or four months. Occasionally I got a pass and went into New York City. I saw my first play in New York, Voice of the Turtle.

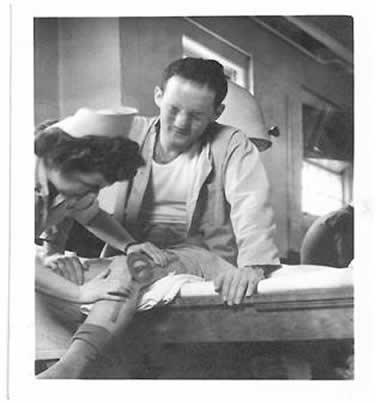

My commanding officer at Ft. Dix came in one day and said I was going to be sent to Wisconsin for physiotherapy and I said, "What's that?" (Laughs) It was later changed to physical therapy. I ceased being a WAC when I was sent to the University of Wisconsin. This picture shows our class in physical therapy. I'm the last one on the right in the second row. We all had degrees before we got to Wisconsin. We marched to class and we stayed in a nice two-story rooming house with a captain as our housemother. She was in the medical corps and is the one seated on the far left.

We spent a year taking courses in anatomy, physiology, pathology, and other courses, all part of our requirements for the Physical Therapy program. Wisconsin was a wonderful school. It was a far different group than the one I knew at Oglethorpe (Laughs). We graduated with certification in physical therapy and were commissioned second lieutenants.

The biggest part of my Army career was at Vaughn General Hospital in west Chicago. I worked with many kinds of disabilities: brain injuries, amputees, spinal cord injuries. The great majority of men I worked with had compound fractures they got from shrapnel, foxhole falls, or gunshots. They were operated on before they came to us.

In this picture I'm measuring a man who'd had a compound fracture.  I'm measuring his range of motion with a goniometer. I'm measuring his range of motion with a goniometer.

One of our major problems was patients whose evacuation from war areas had been very slow. They were so stiff from being in casts so long, and most had infections in their fractures. That infection's called osteomyelitis. We only had sulfa to treat these infections. We didn't start using penicillin till 1943. When you'd go into a ward, the odor from the infections was terrible.

When we got soldiers with fractures, we first treated their bone infections then tried to get them moving gently. We had all kinds of ways of strengthening injured limbs and had considerable success. But some of the patients never did get full range of motion. You see different injuries today, a lot more burns and amputees now due to IEDs [improvised explosive devices]. Surgery and medicine are so much more advanced now.

The man in this picture was being discharged and we were celebrating. I'm left of the man; the other women are pt aides. We wore seersucker uniforms, light-brown dresses and brown stripes, and white nurses' caps.

The GI's I worked with in physical therapy were very appreciative and very polite, to me at least. Most of them were enlisted men. I had some lieutenants. I became friends with many of them and I heard from them after they left, and it makes me cry. (Crying softly) But they did call me "Commando Annie." (Laughs) I was pretty rough on 'em sometimes. I tried to make them do it. I tried to motivate them. They were young and I was young. None of them died while I was there. I had one patient with a serious brain injury and multiple physical injuries and he really hadn't recovered when I left.

I don't recall any of them talking about their combat experiences. I think that was typical of a lot of World War II veterans. If they did talk about the war, it was usually in a light-hearted manner. They really didn't talk about the stress and awful things they'd gone through. They were mostly young men in their late teen and 20's. There were a lot of farm boys from the Midwest. They told me where they were from. Some had ambitions to go back to school.

Did you have to contend with any problem personalities?

No. Sometimes you had to motivate them. I think that's why they called me "Commando Annie." (Laughs) I said things like "get busy," "do your exercises." We taught functional activities. For example, those with spinal cord injuries we taught how to get in and out of a wheelchair. We did gait training of amputees after they got their prostheses.

How about the male doctors you worked with?

They were very ego-centric. They would give strict orders for us to follow. We had to stand up when a male doctor came in the room. I never liked that, but I did it. Fortunately, I was able to be my own person and do mostly what I wanted to do.

Currently, the association with physicians is much improved, and we share goals and concerns for maximal benefit to our patients.

When I was at Vaughn Hospital, we could get away from the job and visit places in Chicago. It took us ½ hour by the "L" to get downtown. We had good dinners at the Old Heidelberg Restaurant. Vaughn Hospital was close to an Italian neighborhood and we went every Friday night for Italian food. Had my first drink (Laughs), a rum and coke. We dated guys some. I had a few dates but nothing serious. I liked Chicago a lot better than New York.

What did you think of the atomic bombing?

I had very ambivalent feelings about the bomb. I think in the long run maybe it was the right move because we would have lost many, many more young men if we had not done it. But I'm sorry we were the first to do it.

The draft system we had then was different from our volunteer army now. The volunteer military has advantages and disadvantages. We have highly trained forces now, but so many of them have to keep going back to combat, and these wars we're in now last much longer than World War II. I'm patriotic but I don't think war solves much.

I got to be good friends with the women I worked with. After service we scattered to various hospitals in Denver, Washington State, Oregon, and other places. For a long time I heard from them once a year--no longer.

I enjoyed my stay in the service but I was glad to get out. After working in physical therapy for four or five years, I went to Stanford University and got a master's degree in physical therapy. I also took a lot of continuing education courses. I went to Stanford under the GI Bill. The GI Bill was wonderful and helped the whole country.

Back then we were pioneers in physical therapy. I enjoyed all my clinical and academic work. Clinical skills were my forte. Physical therapy was a very rewarding career for me.

|