|

Son Dinh achieved professional success as a lawyer in Vietnam. When he emigrated to the United States he could not transfer his law degree here. Fortunately, his ingenuity, diligent study, and hard work enabled him to excel in a new career in electronics at Shands Hospital in Gainesville, Florida. There he met Janet Goode and their friendship and mutual interests in music led to a loving relationship and eventual retirement to Oak Hammock at the University of Florida. In 2013 Son Dinh told me some of his experiences in Vietnam from the time of the Japanese occupation to his emigration to the U.S. His written story appears first here followed by a conversation he and I had.

Friends often ask me to tell them more about myself. I had learned in my French education that “le Moi est haissable.” That means that talking about oneself is ugly. So, this is only a very casual talk, in which I would share some of my thinkings about facts of life, and some real stories happening in my life.

First of all, I was born in the former French Cochinchine, which was part of the French Indochine (Tonkin, Annam, Cochinchine), and which later became South Vietnam. When the Japanese came to occupy Vietnam, I was just 9 years old. I still remember people talking about some kind of blockade of Saigon. Food supplies could not come in. I remember my mother had a substantial rice stock in the house, but for many months, we ate only rice with some watercress and fish sauce. We had a market in the neighborhood, but it was kind of empty. The Allied aircraft came to bomb Saigon almost every day. I remember many nights we kids came out to look into the skies and see the B-29s shining like miniscule diamonds in the moonlight. I thought they were beautiful. I also enjoyed seeing the powerful light the Japanese shone into the skies and fired anti-aircraft guns at the Allied airplanes.

When the news of the surrender of the Japanese came, many Japanese officers living in a house next to the house of my grandparents committed hara-kiri. I did not see them with my own eyes, but the people who gathered in front of that house to look said there was a lot of blood.

Next to our house lived a French family name Chevalier. They were very good friends with us. When the French came back after the Japanese defeat, they gave us French bread and chocolate. For us kids, it was wonderful. My parents sent me and all my siblings to Vietnamese elementary schools so that we could learn about our Vietnamese heritage. After that, we went to the French high schools and colleges for further education. We grew up in a French environment, reading French local newspapers, French magazines, listening to French radio, taking music lessons with private French teachers.

Saigon at that time was nicknamed the Pearl of the Extreme Orient. Life was wonderful. People used to think that the colonialists are horrible people. I think there is some truth in it, but on the other hand, the French did bring to my country a lot of civilization, electricity, railroad, ships, cars, industrial factories. These are historic facts everybody can find on the Internet.

Some French famous pianists came to Saigon to give recitals. I went to listen to them, and developed a love for classical music. It was how I started to study music and the piano. At that time, there was no music school in Saigon, and the only way to study music was through private lessons with the local French teachers. I still remember when I was 12 years old, I went to a violin recital given by a young French violinist who just won 1st prize at the conservatory of Paris. I still remember she studied with the world famous violinist Jacques Thibaud. At that time, I already had a lot of piano studies, but I fell in love with the violin, and started to study that instrument. I had to ask a friend who lived in Paris to get me a good violin from Paris and ship it to me. In short, the French gave me, beside a vast knowledge of the world through the Lycee Chasseloup-Laubat (high school), the love of Western classical music, which is now the happiness of my life.

Unfortunately, a few years later, it was war between the French and the North Vietnamese Communists. It was true that the life in Saigon was not much affected for many years, and I could finish my high school and my law school in a relatively peaceful environment.

About 1955, there was a French captain who had to go back to France. He had a beautiful female German shepherd he was not allowed to take with him back to France. He was desperate and looked frantically for some good house for his dog. I took his dog in. Her name was Diane. Here was the interesting thing about Diane. When she first came to our house, she did not want to hear anything in Vietnamese. We had to speak French with her. But just a few weeks later, she could understand Vietnamese. So I think maybe a dog can learn foreign language faster than a human being.

After graduating from the French Law School in Saigon, I went to Montreal to attend McGill University, where I got a Master Degree in International Aviation Law. After graduation, I went back to Vietnam, and was drafted into the military, where I would spend four years, from 1962 to 1966. My memory becomes fuzzy, so I cannot always go into details. I just try to tell what I can remember.

First, I was sent to a concentration base, where they gave me military haircut and some military clothes. We lived in some very basic wood construction, slept on wood trunk beds, and learned to live basic military life, getting up on time, having meals on time, doing bed and cleaning the place where we lived, etc. For bathrooms, we dug holes in the ground, poured some lime into them, put some wood planks across to sit on. It was so filthy that you have to be tough to use these horrible holes. It seems like these people had no idea how these holes could contaminate the water. About these barbaric sanitary setups, I remember two stories.

One day, a poor guy who had a bad case of epilepsy fell into that hole. It was a big commotion in the camp. Some soldiers pulled him out and threw water on him to wash him. I had a cousin who was a medical doctor. He was so scared of these holes that he could not have bowel movement for many days. One day he collapsed, and they had to take him to a military hospital where they had to take drastic measure to help him have a bowel movement.

After a short time at that camp for triage, we were sent to the military school Thu Duc, where I would spend 10 months for basic military training. After graduation, I became a lieutenant and was assigned to the South Vietnamese Air Forces “Tan Son Nhut” (TSN) base. I was personnel manager of the Air Traffic Control and Météo unit. All my staff had been trained in the US and were very competent. During the Vietnam War, TSN air base was the busiest in the world. Day and night, non-stop take-offs and landings, and practically no accidents. My job was to organize shifts for my staff, keep all documentation (maps, weather forecasts) for pilots, get or give diplomatic clearances to Vietnamese military aircraft to go abroad, or foreign military aircraft to come to Vietnam or just overfly through Vietnamese airspace. In case of accidents, I went out to investigate.

I used to go to the officers’ cafeteria to eat, and listen to stories. One day, I heard this from some Vietnamese pilots just back from a combat mission. They went out with some American pilots, and one of the Americans was shot down by a VC hidden in a tree. According to the Vietnamese pilots, the American pilot made a big mistake by coming to the combat zone three times from the same direction. The VC was waiting for him to come back and just shot him right through his cockpit. The Vietnamese pilots said they never took the same pattern to come back.

One day, I had to go to some airfield in Kontum for some assignment. I do not remember what it was. In any case, it was a formation of three Huey gunships flying from Saigon to Kontum. On the way, I think it was near Pleiku, we were shot at furiously from the ground. The three helicopters I was with just made a turn around, always together in the same formation, to shoot back at the VC on the ground. I was thinking that if the guys on the ground had good anti-aircraft guns, we would all be dead. Why the American pilots did not disperse and come back from different directions so that the VC would not have an easy target? That trip confirmed what I heard before that some American pilots did not vary their flight patterns enough.

The three helicopters I was with flew in vertically, because the region was infested with VC and they could not take the risk to fly in low. So when they landed, it was like a rock dropped from the air. In a very short time, from a very high altitude where it was cold like hell, we were on the ground where it was hot like in an oven. I almost fainted. I looked at the pilots. They sweated profusely, but just talking and laughing as if not affected at all by the heat. I remember that I was thinking they were amazing.

During my service in the military, what I hated most was that we were confined in the base all the times for various reasons, but mostly during coups or coup attempts.

President Ngo Dinh Diem had a caserne of Special Police Forces in front of our Tan Son Nhut Air Forces base. At one time, the military prepared a coup to overthrow Diem. I was ordered to move all my guys out to position them in front of the entrance to the base. My memory of all these events is very fuzzy, and I do not remember the details. I still remember I had my guys install machine guns, rocket launchers and mortars at the entrance of the base, in coordination with some other units. Tanks had been brought in, ready for a huge clash with the Police Forces of Diem.

I remember a funny detail. I was telling to one of my guys to bring his machine gun to one location, in direct view of the caserne of Diem’s Police Forces. He was crawling on the ground, too frightened to stand up. I shouted at him, to stand up to move the machine gun. He said “Lieutenant, I forgot my helmet, if I stand up, I can receive a bullet to my head.” I found it very funny. I told him the chance he received a bullet to his head was one over one million, and threw my helmet to him, telling him to put it on his head. He handed my helmet back to me, and stood up to move his gun. The situation was tense, but after a few days, nothing happened. Diem survived the coup that time, but he was killed in another coup.

As said, most of my military life was administrative. The Vietnam War had been covered extensively by thousands of books and videos, with accurate details. It is not necessary I tell stories where I had no connection.

I remember one high-ranking Vietnamese officer in the base who was allowed to operate a barber shop for the GIs. I do not remember exactly, but it seems like it was $5.00 a haircut. What I remember is that the guy hired beautiful girls to work in his salon. I never went to that place, practically reserved for the GIs. I learned that the girls had to wear white lab coats, unbuttoned at the top, and no bra. They made a lot of money, and many of them got married and went to the USA with their GI husbands. Naturally, our Vietnamese officer owner of the hair salon made huge money too.

A few times on assignments, I saw bodies of VC. One day, on the road, we were driving at around 45km/hour, and on the side of the road, there were four bodies of VC. One of them had the back of his head completely gone, but the face was still intact. It was about noon time, and it was hot, I did not know how long these bodies had been there, but the stink was unbearable, even though we drove by at high speed. A little bit later, I saw some South Vietnamese soldiers carrying another dead VC in a rice field. They tied the arms and the legs of the VC on a pole through his limbs to carry, like you see pictures of tigers killed by the British people in India in the past. When we arrived at the location of our assignment, I saw another body of a VC, leaned against a tree. Someone put a hat on his head and a cigarette in his mouth. At first, I thought a guy was having a nap, but when I came closer, I realized it was a dead VC. There was a note stapled to the tree above his head, saying he was murdering the civilians in the village for not giving support to the VC.

As said, I was mostly annoyed when we confined to the base, sometime for weeks. What did we do to kill time when not on duty? Well, we read. During these years of war, in Saigon, People loved to read stories of martial art. There were some Chinese writers who specialized in writing martial art stories. Their books could be many thousands of pages. It seems like their imaginations are infinite. Their stories keep going on and on and on. When we were allowed to go home for a few hours, we stopped by book stores to rent a big stack of these books, and read them during the nights.

One thing I much dreaded in the military was the Honor Guard. Vietnamese pilots got killed all the time. When they brought in a dead pilot, we had to take turn to stand the Honor Guard. That means two officers wear ceremonial uniform and stand motionless both sides of the coffin for two hours. During my time in the military academy for basic training, I developed bad varices in my right leg and had to go to the military hospital for surgery. Veins in my leg were weak, and standing a long time was for me very painful. Because of my lower rank, they scheduled me to stand Honor Guard all the times.

One night I and another officer were scheduled to come to take the Honor Guard in the middle of the night. When we arrived, two captains who had the shift before us were outside the room where the coffin was. It was in the front room where Buddhist monks took turn to recite prayers for the soul of the dead. We asked what happened. They said that while standing near the coffin, they saw with an absolute clarity the killed pilot coming in and smiled at them. They were so scared that they ran out of the coffin room. I had never seen a ghost in my life, but the two officers were so frightened and sincere that I did believe what they said. The next morning that story was circulated in all the base. Everybody believed it, because these two officers were much respected in the base.

The communists confiscated many things in Vietnam, including pictures. So I don't have any pictures to show.

A Conversation with Son Dinh

You mentioned many coup attempts against the regime of President Diem. I remember 1963 like yesterday: the Buddhist monk burning himself to death; Madame Nhu, the powerful wife of Diem's brother nicknamed the "Dragon Lady"; assassination of Diem and his brother by South Vietnamese soldiers. Then President Kennedy's assassination a short time after he had approved the coup that killed Diem. JFK's murder cast suspicion on those like Madame Nhu who disliked Kennedy.

It was a very complicated time. Diem and Madame Nhu were unpopular. Many of us did not like Diem's persecution of the Buddhists. There were Army officers who hated Diem and high generals that liked him and other officers in the middle. Sometimes it was hard to tell who was on which side. During the coup attempt I described, I was just a lieutenant following orders.

I remember that South Vietnamese general shooting a VC soldier in the street. Can't recall his name.

Major General Nguyen Ngoc Loan. He was Chief of the National Police. The shooting happened a block from my house during the Tet Offensive in 1968. I did not see it at the time. The photo went all over the media.

The incident fueled anti-war sentiment against the South Vietnamese and Americans. Loan looked like a fat oppressor and the VC like a poor underdog. I understand the American who took the picture later apologized to Loan and called him a hero.

Photos never tell the whole story. There were many misunderstandings in that war. A relative told me about an American professor who was against the war. He had a South Vietnamese student who'd been through some of the worst times. The student told the professor about his experiences in Vietnam. After that, the professor changed his opinion and was for the war against the communists.

Many people, including some military, think the Vietnam War was a long, no-win situation at a terrible cost in lives and resources. Do you think the war could have been won?

Yes, if the Americans had kept up the pressure and continued aid to South Vietnam. At the Paris Peace Conference the communists played tricks. I knew a reliable source who had inside information on the conference. He told me that any papers the communists signed they would just throw them away later and go on fighting. He said the Christmas bombing in 1972 hurt the communists so much they were close to surrendering.

William (Bill) Ebersole's life has been one long success story. At age 14 he earned his Eagle Scout badge and began 2 months of service in the 1939 session of the Florida Legislature as a page in the House of Representatives. There he associated with and learned from officials who have received high marks in Florida history including Governors Leroy Collins, Fuller Warren, Dan McCarty and others. A decorated World War II veteran and University of Florida graduate, Bill began his distinguished thirty-six year career at the Gainesville Sun in 1948 while a University of Florida student, as a linotype operator working part time on the night shift for 75 cents an hour. He became a full time employee in the advertising department of the Sun during the summer of 1949 after he completed his Journalism degree. A year later he married his pharmacist wife Wanda and they raised two children. He became the Advertising Manager of the Sun while it was still privately owned. It was sold in 1962 to Gardner Cowles, owner of Look Magazine and he became the General Manager in 1966. When the paper was sold in 1971 to the New York Times Bill was named its Publisher and held the position until he retired in 1985. In 1986 Bill began a second 20-year career in commercial real estate. His 61-year marriage ended in 2011 when his wife Wanda died after a 14-year bout with Alzheimer’s. Bill married his second wife Anna in 2012 and they reside at The Village, a retirement community in Gainesville, Florida, where they are enjoying leisure activities and traveling. In late 2012 I interviewed Bill about his experiences as an Army Air Corps pilot in World War II.

I was 18 when I joined the Army Air Corps in 1942, a month following my 18th birthday. I wanted something nice and safe, so I applied for the Army Air Corps. Living in a foxhole didn't appeal to me. I did basic training in Miami Beach. After basic I went to Nashville for classification. I scored high enough on the tests to be classified a pilot trainee. I was then sent to a three month stay for ground school training in a college training detachment at Clemson University for pre-flight training and then began my pilot training at a Primary Flight School in my hometown of Arcadia, Florida. My father was the publisher of a weekly newspaper in Arcadia. His print shop did a lot of printing for the Air Corps and he knew a lot of air force personnel so was able to somehow influence the military powers to send me to Arcadia for my primary flight training.

My primary trainer was the two-person bi-wing Stearman PT-17. Training in Arcadia was wonderful. The whole time I was engaged in flight training in Arcadia I always knew where I was because I had hunted and fished in the area since my early youth. After about 30 hours of flight training I had a change in instructors and received an earlier than usual flight check that enabled me to begin my acrobatic training earlier than the other trainees. That kind of flying wasn't usually done until a trainee had 40 to 45 of the 60-hour program completed. I enjoyed the aerial acrobatics and was selected to do acrobatics for my squadron at the graduation of my primary flight class.

My next assignment was at Gunter Field in Montgomery, Alabama, where I flew a BT-13 Basic Trainer, a much larger 2-place plane used to teach more advanced flying skills. From there I went to Craig Field in Selma, Alabama, and became proficient in the AT6, a larger, faster and much more advanced plane that had a controllable pitch propeller, retractable landing gear, landing flaps, fixed guns in the wings, navigation instruments and many other features that I had to master before moving into combat fighter planes. I completed the advanced flying course and graduated in the Class of 44-D (the fourth month of 1944) on April 15, 1944, receiving my commission as a Second Lieutenant with my new pilot wings.

So you'd been in training for about two years.

That's right.

What stands out the most for you in flight training?

I always enjoyed the acrobatics and was amazed that the Army Air Corps, which it was called until 1947, could take a person that was barely 18 years old, who had never been in an airplane before, and train him to be proficient in the sophisticated planes that I was taught to fly.

I always looked very young. I remember an incident that happened a few days after I became a Second Lieutenant when I was walking down the street in Selma, Alabama, where I received my advanced training. I passed a Sergeant coming down the street who saluted me, and then said: "Lieutenant, can I ask you a question? I answered "Sure, Sergeant, what is it?" he said “Sir! How old are you?” (Laughs)

A funny thing that I remember happened on a solo cross-country flight in early 1945. I was flying solo in an advanced trainer single-engine AT-6 on a practice cross-country flight out of Selma, and overheard on the radio two men talking in another plane. They were apparently practicing instrument flying: one was flying on instruments under a hood, and the other on lookout for other aircraft, etc. They probably thought their conversation was totally private, but they'd mistakenly switched their intercom to a live broadcast mode. One said, "You take it Joe. I'm all (fouled) up!" The word used was not "fouled," but a similar four-letter word commonly used in the military. The air traffic control tower came on and said, "Will the pilot making that last transmission please identify yourself." No answer. The tower asked again. Still no answer. For the third time the tower asked the pilot to identify himself. Then a voice came over the radio saying "I'm not that (fouled) up!" (Laughs)

I can imagine what that "bad" word was. (Chuckles)

Oh yeah! It was banned for use on the radio along with many similar words. After graduation, we started flying real fighters. I got 10 hours in the P-40. That required a new skill handling a single engine plane such as a P-40 or a P-51 with such powerful engines. The reaction of the propeller spinning in one direction forced the plane to roll in the other direction. This was controlled primarily by the rudder. In constructing the plane, the rudder was permanently set to correct a normal amount of torque, but a dive required a great deal more of left rudder pressure, and a climb required more right rudder pressure.

We had to be extra careful as we began flying these planes that were so much more powerful. We did not have an instructor in the plane with us. Everything was solo because it only held one person. And it became the most dangerous time of a new pilot's career. After a new pilot first became skilled at flying and started becoming confident, he began thinking he could master the plane and could do almost anything he wanted to with it. It was like a young kid driving a car for the first time and thinking he can do all kinds of things behind the wheel. That's when a lot of accidents happen. Overconfidence caused serious accidents and crashes. There were a few pilots that talked about flying under a bridge. That kind of flying was just foolishness. I was pretty conservative and never took that type of unnecessary risks.

After training in the P-40 I went on to a P-51 Overseas Training Unit (OTU) school in Bartow, Florida. The P-51 had a real powerful engine, 1500+ horse power. I ended up with about 240 hours of flying time in P-51s. My roommate and I got in a plane every chance we could get. We volunteered to pull targets. I remember pulling a target about 10,000 feet up over Clearwater. The target was about 70 or 80 feet long and 8 to 10 feet wide. Planes would make passes at the target, trying to approach it from the side and shoot at it at an angle of about 90 to 45 degrees. It could be dangerous for the towing plane if the planes attacking the target dropped too far to the rear of the target to take their shots.

The P-51’s I flew in training had one operating 50-caliber machine gun in each wing. The guns were permanently mounted in the wings in a fixed position. The pilot aimed the plane using a gun sight mounted on top of the dash board. The bullets were dipped in a chalk-like paint that was a different color for each plane so when the target was brought back to the base, it could be determined which bullets scored hits on the target. For ground gunnery training, they placed targets on an ocean-side key in the Inland Waterway near Clearwater and we'd dive down and shoot at them.

My roommate and I had the highest gunnery scores in our class and I'm sure that's why they pulled us out of our training in Bartow and sent us over to Lakeland as replacement pilots to join a group training there for long-range bomber escort missions. When we flew in combat, all six of the gun positions were used, three in each wing. Out of every five bullets we shot, two were incendiary, two were armor-piercing and one was a tracer.

We had twice as many pilots as normal in our Group because of the extra long range of the missions we would be flying so when we left Florida for overseas duty the pilots were divided into two groups. One group went to San Francisco and was put on an aircraft carrier being used to transport the planes to Guam. They were unloaded there and were being prepared for the long range flights they would soon be making after the landing strip was completed on Iwo Jima.

The second half of the pilots, of which I was a part, went to the port of embarkation in January 1945, going by train from Lakeland to Seattle and then sailed on a Dutch ship to Hawaii where we stopped for a couple of weeks, then made short stops at Enewetok, and Saipan, arriving at Iwo Jima in April. We sat parked off the shore for about a week. The island was pretty well secured by then, but there was still some enemy resistance. While we were still on the ship we saw a lot of trip flares going off at night. Japanese troops hiding in caves would come out of hiding at night seeking food and water. About a week before we left our ship, a large group of the remaining soldiers in a suicide attack ran through the tent area where a group of early-arriving pilots in another Group were camping and threw hand grenades into the tents successfully killing about a dozen pilots.

After coming ashore from our ship, we were so unnerved that for a number of nights we slept on the ground under our cots, made up to look like someone was in them, with our cocked .45 pistols at our sides. No one dared to venture from the tent after dark—for any reason.

We had to wait for the construction of the air strip to be finished before the rest of our squadron could bring the planes up from Tinian so we could begin flying again. We slept in the wall tents for a while.

I was fortunate because from my Boy Scout training I knew a lot about camping, hunting, fishing, living outdoors, and even starting a fire without matches, practical things like that. Most of the pilots I was with did not have any outdoors background. They didn't know you had to punch a hole in a can of beans being heated on an open fire to keep it from exploding. (Chuckles)

I flew my first combat mission, on May 1, 1945, which was a dive-bombing mission at Chichi Jima, located about 45 minutes from Iwo. I dropped two 500-lb. bombs on a radio transmitting target that had been notifying the Japanese mainland when planes were over the area heading for Japan. I made a second mission there several weeks later. This is the same target where President George H. W. Bush, as a Navy pilot, was shot down during the war.

Did you get into any dogfights?

No. I had been trained to handle enemy planes attacking us and I saw Japanese planes, but I didn't have a chance to shoot at any. After only a few of our missions which were to protect the B-29 bombers on their daylight raids to Japan, the Japanese stopped attacking the B-29’s because their losses were so heavy. We were then assigned specific airfields to attack. Sixteen of our planes would attack an airfield. Twelve of the planes would drop down from 15,000 feet to tree-top levels while four planes providing top cover to protect the lower planes in case enemy fighters came around. If weather prevented us from attacking the airfields we would seek secondary targets: boats, trains, or anything that had any military value, even radio towers, electrical transmission power lines, etc. Most of my targets were in and around the Tokyo area.

We weren't too worried about Japanese fighters coming after us. They were saving their planes anticipating an invasion of Japan. We had no official word but we all felt that we were moving toward an invasion of the mainland of Japan in the Fall and this was confirmed after the war. We knew if there was an invasion we'd be in the thick of it.

On a strafing mission, we'd get fifteen miles from the target and dive in at 400 to 450 miles an hour. Once at tree-top level their radar couldn't pick us up. When we got a target in our gun sight, we were often going so fast that we were in a nose-down position to stay down because of the added speed, so we had to pull the plane up so we could fire down at the target. We came in so fast they couldn't hit us--their fire just went behind us but pulling up to fire was dangerous because we became a more vulnerable target. I got credit for destroying a twin-engine bomber on one mission and probably destroyed a single engine fighter on another.

On one mission when several of the primary targets were closed in by bad weather, we spread out in all directions, seeking other targets. We found a train moving into a rural station and several of us dived down and attacked it. I picked out what at first glance appeared to be an engine and clobbered it but it turned out to be a caboose. It was backing up. Meanwhile planes from another of our squadrons found it and started moving in on it as well. My flight leader called me and said, "Bill, let's get out of here before we run into one of our own planes.”

The two of us flew South toward the Inland Sea where we saw and attacked a 100-ft freighter. We were over the water so there was no ground fire to worry about. Starting from an altitude of about 1000 feet, my flight leader dove down and attacked the ship in a pass not unlike the ground gunnery exercise we received in our advanced training. As he pulled up I followed doing everything that helped me get such good scores in my training: I centered the needle and ball on the instrument panel, dropped ten degrees of flaps, slightly lowered the rpm, and got into close range before firing. We pulled up, circled, and made a second attack. My gun camera film later showed that most of the rounds I fired did in fact hit our target. We left it burning and I got credit for probably destroying the ship.

Another time I was the fourth plane in a 4-plane squadron attacking a Japanese aircraft carrier in the Inland Sea. We peeled off one at a time and dove down at full power to individually attack the ship. I could not shoot at the carrier until the three planes ahead of me shot first. This was the fastest I ever flew in a P-51. As I began pulling out of the dive, I blacked out losing all of my vision but could still handle the plane’s controls. You can't do much damage to a carrier with 50-caliber machine guns. It was stupid to put us to that kind of risk. We didn't have any bombs to drop on it. We had only machine-guns.

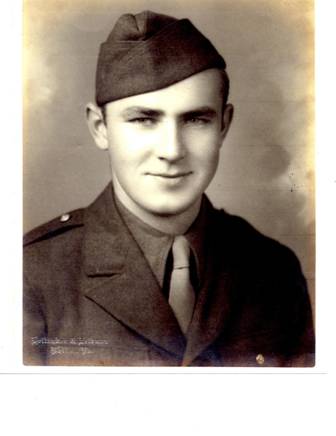

Bill Ebersole from his unit's impressive album, 506th Fighter Group: The History of 506th Fighter Group, Iwo Jima 1945. The cartoon (top left) shows an American pilot shooting a Japanese soldier out of an outhouse. The title means "Honorable Mistake." The description gives Bill's account of his squadron's attack on an enemy aircraft carrier which he told me earlier. It also lists Bill's decorations: Distinguished Flying Cross , Air Medal with Three Oak Clusters, Distinguished Unit Citation, Asiatic Pacific Campaign and American Campaign medals.

Did your squadron suffer any casualties?

On one mission on June 1st, 1945, out of about 245 P-51 planes on a mission to Japan, a total of 29 P-51 planes and 28 pilots were lost trying to go through a severe cold front about halfway between Iwo and Japan. On one mission on June 1st, 1945, out of about 245 P-51 planes on a mission to Japan, a total of 29 P-51 planes and 28 pilots were lost trying to go through a severe cold front about halfway between Iwo and Japan.

After this, great care was taken to be very aware of dangerous weather conditions.

On the way back from a one strafing mission, I was flying on the wing of my element leader when his plane was hit by anti-aircraft fire. I knew the pilot. We all lived together and trained and flew together. His plane was trailing coolant as we headed back to Iwo. Heavy smoke began streaming out of his plane and he began preparing to bail out. We had already passed one Navy rescue ship and were heading toward another that could've rescued him when he was in the water. He did all of the things we were told to do: eject the canopy, lower wheels and flaps, trim the plane, slow it to a near stall, and exit over the left side of the plane. But as he bailed out he hit the plane's horizontal stabilizer. He fell through some clouds but we never saw any evidence that his chute ever opened.

My flight leader and I remained in the area for fifteen or twenty minutes but our fuel was low so we had to leave. We continued on toward Iwo. Our planes had limited navigational aids. I was flying on the wing of my flight leader when my instruments indicated we were missing Iwo. When I called him, he said he had been having some problems with his instruments and would fly on my wing using my instruments to get us home. I turned almost 90 degrees to the left. Iwo came in sight 10 or 15 minutes later. I landed with only a 5-minute supply of fuel left. This was my longest flight in a P-51, eight hours and twenty minutes. My VLR (very long range) flights usually averaged 7 ½ hours to 8 hours.

How did you cope with anxiety, fear?

I don't recall ever having any fear. The training was so good it helped you to be level-headed and feel like you're in control. There were some things you couldn't control, but the training gave you a sense that there was a lot you could. It's just amazing when you think about the training program. Like many back then, I was just a youngster when the war started, never been in a plane before, and they were able to take a lot of us and teach us how to do all these things with an airplane in combat. There were some that became very fearful. One man came in after a mission and said, "You know, this is really dangerous. I'm not gonna do it anymore." They shipped him back to Hawaii for rest. When he came back, he still wouldn't get in a plane again.

Did you ever have any misgivings about hitting civilians?

I wouldn't have made a good ground soldier. I did have second thoughts about a freighter that I seriously shot and probably destroyed in the Inland Sea south of Tokyo. It didn't seem to be armed, didn't shoot at us, but we made strafing passes at it. I did the most damage to it. It was pretty much destroyed.

I realize the two Atom Bombs dropped on Japan killed thousands of Japanese but without them, we would have attempted to invade Japan and the loss of life by the allies and by Japan would have been unimaginable and may have exceeded the atom bomb losses. I doubt that I would have survived an invasion of Japan because I would have surely been in the midst of it.

A few weeks after the war was over a friend, who shared the same plane with me during the war, and I decided we would see if we could hitch a ride on one of the transport planes that stopped at Iwo to refuel before heading on to Japan. We decided we would take the risk of going AWOL (Absent With Out Leave). The friend said “Bill, we've been sticking our necks out around these islands so long the Army's not gonna do anything to us.") We filled our pockets with things like sugar and cigarettes and candy bars and climbed on a plane heading to Japan where we spent several days, including my 21st birthday on September 30th, 1945, roaming around Yokohama and Tokyo.

Yokohama was burned out and in total rubble and ruins with only a few building shells standing. There was some destruction in Tokyo but there were still many areas that seemed untouched by the war. The people were very polite to us. We met a man on the street and were somehow able to communicate that we wanted to find a kimono. He could not speak English but understood what we were looking for. He took us down some narrow streets and he led us to his home. We left our shoes at the door, entered his home and sat on the floor while his wife and daughter modeled several different kimonos that he was willing to part with. We traded him all of our goodies plus the friend's army wrist watch for two kimonos which my friend wanted to take home to his wife. They were very nice to us. I later told my buddy, "This is just amazing how nice these people were. It changed my whole outlook on the war. The soldiers we fought were the villains, and the civilians were very friendly and likeable. I don’t believe I would be that way to anybody that had just conquered us." No one ever said a word to us when we returned to Iwo.

This war stuff is very bad. The politicians want something another side has, and they get the people all lined up behind them and go to war. It's still going on today in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq, and other places.

I flew my first mission on May l of '45; I flew my last mission on August 5, 1945, the day before we dropped the atom bomb. I was on Iwo Jima and didn't know anything about the atom bombing till later. Hiroshima was as far away from us on Iwo as Miami is from Chicago.

What do you think has been the biggest change for the United States since World War II?

Democrats and Republicans used to work together much better than they do today. Eisenhower, Nelson Rockefeller, and Ronald Reagan would work with Democrats. The two parties would get together and hash things out, compromise, arrive at solutions they could live with, and the country could move forward. But in recent years Democrats and Republicans have become extreme parties, mostly uncompromising. That's got to change. We can't keep on going the way we are now. This grid-lock we have today has got to be broken. If we don't break it, it's going to break us.

I have a concern for the poor people and the disadvantaged people. We've got to look out for them. One time I played in a golf charity for the benefit of families with small children, so they could have decent shelter from the rain and cold. This friend, who was a regular golf player in my golf group, wrote me a note and said, "I'm not gonna give to that. I worked for my money. Let them get out and work for theirs." That's such a shallow and very selfish attitude that is shared by far too many people today.

We don't have any statesmen today. We got a lot of politicians who are looking out for their own interests rather than the good of the country. We need to have statesmen again, like Florida’s Leroy Collins, Bob Graham and others who work for the good of us all.

Eva Maráková Eichhorn was born in Kroměříž, Czechoslovakia (now two countries, the Czech Republic and Slovakia). She grew up in Němčice nad Hanou, a small town, where her father was a postmaster and her mother a homemaker. Since 1978 she has lived in the United States, most of the time in Gainesville, Florida. Her first job was an enjoyable stint at the University of Florida Library. Then she joined UF's Department of German and Slavic Languages and Literatures as a professor of Russian. "My students were brilliant," Eva recalled. "What took three years in Brno where neither the students nor the teacher really wanted to study or teach Russian, my American students were able to learn in one year." The College of Liberal Arts awarded Eva for Outstanding Undergraduate Teaching (1991), and The Division of Student Affairs honored her for Outstanding Service And Dedication To UF Students (1994). A year before retiring from the university, she submitted a proposal to teach Czech at UF. It was granted and Czech is offered as one of the languages in The Center for European Studies. She is still involved in the Czech program at UF and occasionally teaches a class in the Prague Summer Program. She has two sons by her first marriage and two grandchildren. The late Heinrich Karl Eichhorn, her second husband whom she married in 1977, was an astronomer of international renown after whom an asteroid is named.

What do you think was the major historical development (long-range cause) that led to the movement called "Prague Spring"?

I would have to start at the end of the Second World War when the era of domination by the Soviet Union started. Gradually, the liberators became oppressors, in 1948 a communist regime took over Czechoslovakia, and our previously prosperous country became poor. People lived like in a cage, isolated from the free world by the Iron Curtain. Many of us yearned for freedom and eventually that desire took the form of the Prague Spring in 1968.

How did communist oppression directly affect you and your family?

We lived in a nice two-story house that belonged to us. There was a post office on the ground floor and our apartment on the second floor. The post office moved out just after the end of the Second World War, and we were planning to use the whole house for ourselves. My father had become disabled and living on the ground floor would have made it a little easier for him to get out and enjoy the fresh air. But because there was supposedly a shortage of living space and, probably, because my father was an outspoken adversary of the communist regime, we were not allowed to do that. The lower part of our house was rented to various institutions for a nominal rent without my parents' permission.

In the 50s when the communists collectivized the farms, farmers were losing their land or were sent to prison if they refused to join collective farms. My father became an advocate for farmers in our town, and he had a file cabinet full of "cases." Sometimes he would ask me to rewrite some grievances by hand because his typewriter became too well known to the authorities. Every day my father would

listen to the Voice of America and make notes so that he could tell people coming to our house what was new behind the Iron Curtain.

After I finished the elementary and middle schools in Němčice, I applied for admission to the Gymnasium in Kroměříž. My application was turned down because the official said my grades weren't good enough. My grades were straight A's. After my father wrote an appeal, I was admitted to the Gymnasium in Jesenik, six hours by train from my home. In my class, there were two other girls who were sent there in order to get us out of the influence of our parents. After one year, all three of us were allowed to return to the gymnasium closer to home.

In 1956 I applied for admission to the College of Philosophy at Brno University where I wanted to study Czech and German languages and literatures. Everybody was telling me that I had no chance to get there because of my family background. I did pass my entrance exams in both Czech and German; about a month later I received a letter telling me I was admitted to study Czech and Russian. Later I found out that some people were not permitted to have access to Western languages. I was obviously one of them. So I studied Czech and neglected Russian but graduated with a degree in both. Interestingly, it was almost always Russian that helped me to get a job. A year before my graduation, my fellow students and I were offered an application for membership in the Communist Party. I don't know how many of us applied; some of my friends did, but I did not.

The deaths of Stalin (and Gottwald) 1 in 1953 and Khrushchev's famous speech at the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1956 brought some hopes for changes. But demonstrations and uprisings were always brutally crushed by the existing communist regime. I didn't expect to live long enough to see the situation change.

Where were you when you first learned of the Prague Spring movement?

In 1967 I was living in Brno, working, having two children, the younger one with serious health problems. My major concern was my family and I was not interested in anything else at that time. I knew, of course, that there were some changes in our communist government. It looked like the old Stalinist Guard was being replaced by a new group, more open to some reforms. In January 1968 Alexander Dubček was elected First Secretary of the Communist Party and everything started to change. It was probably my favorite newspaper Literární Noviny that made me pay attention. Censorship was lifted. Articles were interesting, critical, touching on subjects nobody was allowed to write about before such as political-philosophical discussions on civil liberties and guarantees, Czech-Slovak relations, religion, the political processes of the 50s, etc. Long forbidden authors like Jan Zahradníĉek were publishing again.

How did you first react to Prague Spring?

At first, I was skeptical. I did not believe that things were going to be much different than before. In my opinion, it was just a new group of communist leaders taking over and replacing the old group. After all, they were all communists and, in their speeches they always emphasized the leading role of the Communist Party in our future. But, later on, I started to entertain the thought that, maybe, this was a different Communist Party than before.

What did those closest to you first think about it?

I had seventeen colleagues. About half of them were Communist Party members. Out of those, probably just one was a real communist and she did not like at all what was happening. Another one or two were careful enough not to show what they were thinking. All the others, both party members and non-party members were excited and hopeful. I don't remember if any of my colleagues joined this "new" Communist Party during the Prague Spring but many people did.

At the time I was working at the Brno Military Academy. My boss pressured me to join the Party. The Party wanted only young people up to age 30 and I was just under that age. I kept putting him off. He had a heart attack, there was all the chaos of Prague Spring, and by the time it was over I was too old for the Party. (laughs)

As Prague Spring developed over several months in 1968, what did you and those closest to you think about its chances for success?

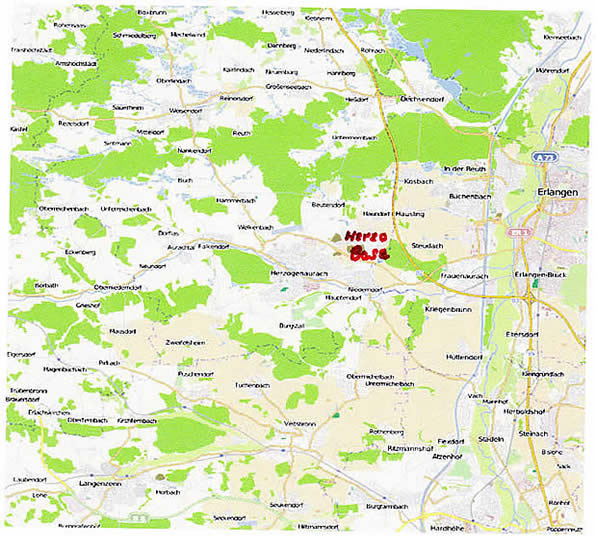

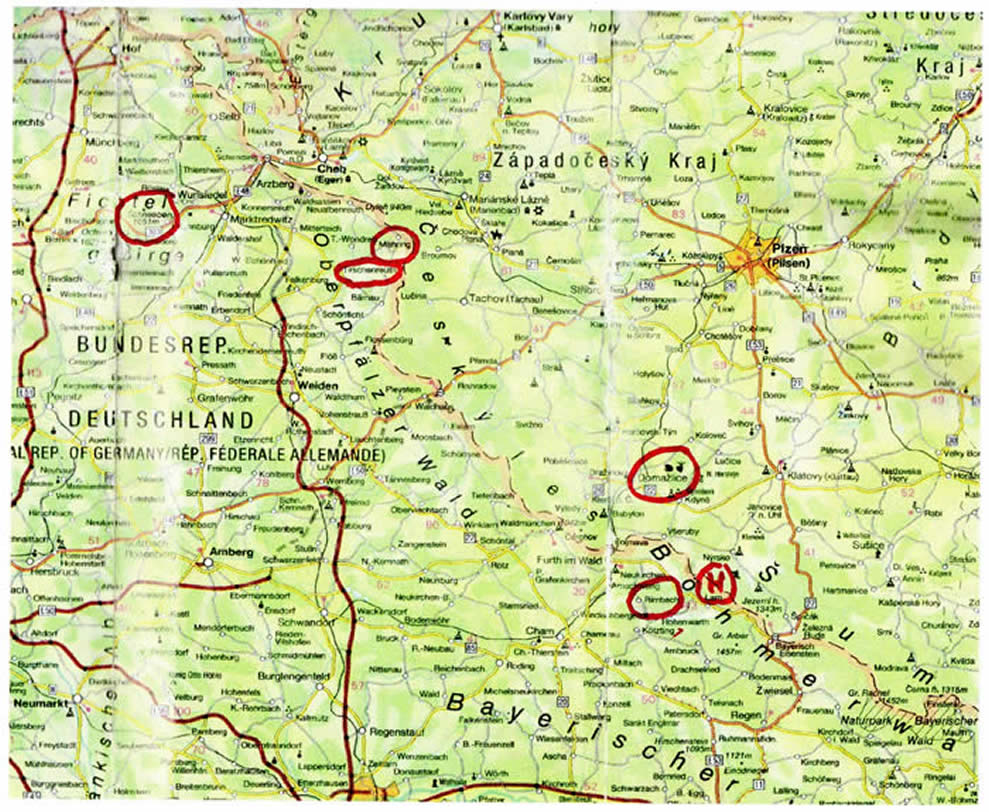

In summer, our family went for vacation to a mountain resort. I still did not trust the new development completely but the chances for success looked good. The Czech government did not want to separate itself from Moscow (many people were hoping that it would) or leave the Warsaw Pact. There was no reason for Moscow to feel threatened. When our stay in the resort was over and before returning home to Brno, we stopped at Němčice to visit with my mother. It was in the morning of August 21 when my mother went out to buy some fresh bread and came back with strange news. Somebody heard on the radio that the Russian army entered our country at night and there were tanks on the streets of Prague and more airplanes were landing at the airport. It was a shock. We could not believe it. But soon there was a newspaper with pictures and it was true.

How did the invasion of Czechoslovakia by Warsaw Pact forces affect your daily life? Were you ever in danger?

We stayed with my mother in Němčice till the end of August. This town has one advantage in time of war. There is a railroad bridge over the only road going through the town. The bridge is low and that is why no tanks can enter. But many people were afraid that there would be a war. It seemed to be safer to stay there as long as we could. Neither my mother nor her neighbors had TV. We were listening to the radio and reading newspapers but the information was scattered. We could not get a clear picture of what was happening. There were rumors that in a town nearby somebody was shot. It turned out to be true. When we returned to Brno, the worse was over. I did not go downtown. I did not see any Russian soldiers at that time. I worried about my children, about our future, and, of course, I was, terribly disappointed.

What was the most compelling thing that you learned about Soviet troops during their invasion and occupation of Prague?

People were saying that the soldiers were mostly very young. Many of them seemed to be from eastern parts of the Soviet Union. Some of them were not sure in what country they were. They were scared; they seemed to believe that they came to help Czech people and did not understand their hostile behavior. I heard the Soviet soldiers were kept in strict isolation (probably for their own safety). Later, when the presence of Soviet soldiers in Czechoslovakia became permanent, the resistance of the Czech population was expressed in seemingly insignificant actions like refusing services. My American husband witnessed a situation in a tobacco store in Olomouc: a young Russian soldier wanted to buy cigarettes. The saleslady told him she did not have any, but the cartons of cigarettes were clearly visible. The soldier did not dare to argue and left confused. Later, there were Russian stores in every city with a Russian garrison. Very often people would tell the soldiers they did not understand Russian. This was not true because since 1948, everybody in Czechoslovakia learned Russian starting in elementary school.

Any other situations in this critical time that you recall?

We returned to Brno at the very end of August in 1968, just before the school started. My oldest son was eight years old and his school was at the walking distance from our apartment. I could see him from our balcony walking with other children down the road, passing a column of tanks parked along the street. That picture got stuck in my memory. The tanks just stood there for about three more days. Later, I found out that just a week earlier the city was not that calm and was very tense. A friend of mine told me that her student from the military academy called her the night of the invasion and recommended that she and her family get out of the country as fast as possible. She also told me that Brno Military Academy supplied all ambulances with gas during the first few days after the invasion and one of the high ranking officers was seen driving an ambulance himself.

During the Prague Spring, my first husband got an invitation to teach astronomy in Tampa, Florida, for one year in 1969. USA was for sure not one of the selected countries, but everything was possible during the Prague Spring and he got permission to go to Tampa. Unfortunately, I did not get unpaid vacation that was usually granted to spouses in such a situation.

Prague Spring was over in 1969, travel became more restricted, and my only possibility to join my husband was to end my employment with the Brno Military Academy and trust the oral promise given to me by a commander of the academy that, if I come back, I will get my job back. After spending a year in Tampa thinking about the situation back in my country, my mother and my marriage, I decided to go back. My whole family returned to Brno. I did get my job back but my husband did not. My marriage did not survive the difficulties we went through and three years later I was divorced. In 1977 I applied for permission to leave the country with both my children. For the whole year I did not get any answer and I was discouraged to ask. In 1978 I did get the permission and left.

How does Prague Spring compare to the 1956 Hungarian uprising against Soviet domination?

The Hungarian uprising turned into a bloody revolution. Hungarian people fought the Russians with guns. Alexander Dubček constantly urged Czech people to stay calm and the army was instructed not to resist. There were casualties but compared with Hungary, the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia was relatively bloodless. Also, Dubček's political program was "socialism with a human face" where the Communist Party would still play a leading role and Czechoslovakia would still be a loyal member of the Warsaw Pact. That was why the

Dubček government believed Moscow would not feel threatened and would not invade the country as it was the case in Hungary.

Why do you think that Prague Spring failed?

I think that Prague Spring was destined to fail from the very beginning. It was naive to believe that Moscow would tolerate the reforms envisioned by the new Dubček Party leadership. Also, it seems to me that Dubček overestimated his personal relations with the Soviets. When the troops of five Warsaw Pact nations invaded and occupied Czechoslovakia, Prague Spring was over.

What do you think has been the legacy of Prague Spring and the Soviet occupation for the present Czech Republic? What do you think has been the legacy of Prague Spring and the Soviet occupation for the present Czech Republic?

When I think about my feelings during the Prague Spring I come to the conclusion that for me, as for most of us, it was all about freedom. I agree with Jiří Pehe that "... desire for freedom despite external danger ... we should consider one of the most important legacies of the Prague Spring." Here is an excerpt from Pehe's article that I have translated into English.

Czechs and Slovaks have many reasons to look back to 1968 with pride. The model of democratic communism was indeed utopian, but when it was later used in the Soviet Union, it began to change the communist dictatorship into a pluralistic political system which contributed to the fall of communist regimes in Eastern Europe.

While Soviet tanks crushed the "socialism with a human face"--although even this idea eventually came back in the form of glasnost and perestroika--they failed to fully suppress the struggle for human rights. This soon came back in the form of an ideological base of dissident movements in the communist bloc, which ultimately contributed to the collapse of communism together with the revitalized virus "socialism with a human face" that Gorbachev brought to the Soviet system in 1985. 2

1 Klement Gottwald (1896 –1953) was a communist politician and longtime leader of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia.

2 Jiří Pehe. "What is the legacy of the Prague Spring 1968?" CRO 6, 8. 21. 2008.

Leonard Emmel was born in Wilson, Arkansas, and lived in a number of other places: chiefly Auburn, AL; East Lansing, MI; and Bushnell, FL. In 1935 he and his family moved to Gainesville, FL, where his father, a veterinarian, took a position in the Animal Husbandry Dept. at the University of Florida. A pre-med student at the University of Florida (1941-1943), he enrolled in the University of Pennsylvania Medical School in 1944 and completed his residency in 1949. He also served a residency in the Thayer VA-Vanderbilt medical program (1950-1951). After two years of Army service during the Korean War, he began practicing internal medicine in Gainesville, FL in 1953 and continued that practice until his retirement in 1989. Leonard and his first wife, Rachel Bushnell Rodenbach, 1 had three children, seven grandchildren, and two great grandchildren. Rachel died in 2010 of multiple melanoma. Leonard and his second wife, Linda Lucille Pennell, 2 now reside at Oak Hammock at the University of Florida. Leonard recounts the highlights of his medical service in the US Army.

I was accepted at the University of Pennsylvania Medical School for the class entering in January 1944. The Army drafted me in December 1943 and sent me to Camp Blanding for about a month. Since I had been accepted to medical school, I was sent to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and enrolled in the Army Specialized Training Program as a Pfc. I attended medical school at Penn until April 1947, the same year I was discharged at Fort Meade, Maryland.

After my residency at Penn, I worked for two years in their Department of Pharmacology (1949-1950). We measured the effect of 100% Oxygen on cerebral blood flow at 3½ atmospheres pressure. This was fascinating basic research done in a pressure chamber under the leadership of Dr. Christian Lambertsen, who was the father of the Navy Frog Men. While he was a med student at Penn, Lambertsen devised an underwater breathing mask.

During the Korean War, I served as a 1st Lt. in the US Army Medical Corps and was stationed at Camp Chaffee, Arkansas (1951-1953). The head of our hospital was a Colonel, and the head of our Medical Service was also a Colonel, both regular Army. Beneath the Colonel most of the officers were non-career officers: 1st Lts. or Captains serving for a period of two years. Our morale generally was good as we had only two years to serve and then we would return to civilian life.

My residency and pharmacology training qualified me as a specialist in internal medicine. I had Dispensary duty every morning for sick call lasting one to two hours; then I reported to the Cardiac Ward at the hospital where I was in charge the entire two years of my service. We handled heart disease, a few general medical patients, and heat stroke. Camp Chaffee was an infantry training base, and we supported the basic training of infantrymen. A number of trainees had severe cases of heat stroke. These cases were my challenge and responsibility. Our hospital did not receive combat casualties. My impression was that medical and surgical casualties from Korea went to hospitals in Hawaii or California.

Heat stroke victims constituted an urgent emergency. We knew that the man's life was at risk, in our hands, and we had the means to save him and possibly prevent brain damage. A soldier would collapse during his training, while on the march for instance, or while undergoing extreme physical activity in hot weather, and be completely unconscious with an elevated temperature of 106-107 degrees. In the field their flushed face, skin extremely hot to touch, and unconsciousness indicated the need for immediate attention. I recall patients with temperatures of 108 or 109 degrees. The longer their temperature remained elevated, the greater the chance that they would suffer severe brain or liver damage. This was something we tried to prevent. Oddly enough, these patients stopped sweating.

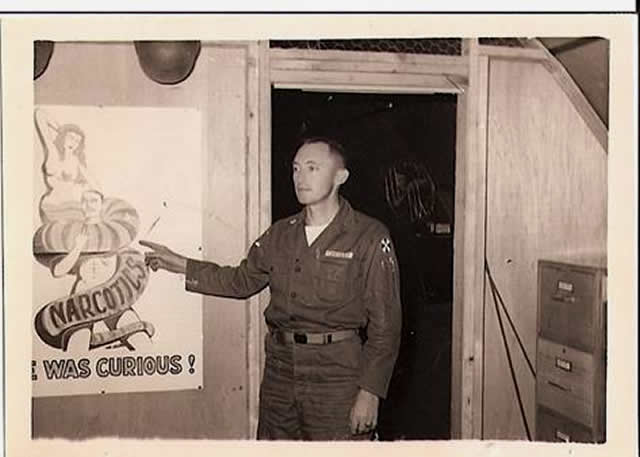

Leonard Emmel as a soldier-medical student at the University of Pennsylvania (ca 1944)

The best treatment at that time was lowering the temperature of these men as swiftly as possible. The course we finally settled on sounds barbaric, but it was successful and we did not have any casualties or organ damage. The patient would be placed in bed, stripped naked, and we would sponge the individual off with ice water, even put ice cubes next to their bodies. Four of us, all medical personnel, would do the sponging at a feverish pace, two of us at the upper body and two at the lower body. After a few minutes of constant sponging, the victim would lie in a small pool of ice water. We monitored his temperature throughout this process. At first we had little effect despite our frantic efforts. I recall after about 10 or 20 minutes the temperature might begin to decline. This tiny progress encouraged us greatly, for it showed our efforts were beginning to take effect. Our treatment might be necessary for an hour or two. The patient remained unconscious and unresponsive all this time.

With time the patient's temperature would decline to levels of 101-102 degrees, and we slackened our efforts. When it fell to 99 degrees we stopped sponging as the worst was over. During the course of treatment an IV of saline would be started to hydrate the victim. The patient would gradually return to consciousness some time after his temperature subsided.

The sponging required teamwork with four people working at full speed, one person in charge of the group, a least one person keeping four buckets of ice water always ready. One person had to keep a close eye on the temperature.

We medical officers discussed whether it would be efficacious to put the patient in a bath of ice water, but we feared so sudden a shock could be harmful. We applied to the Army for a grant to study heat stroke, but we were denied.

My service in the Army was beneficial in a general sense. The greater the extent of one's experience, the greater the source of knowledge one draws upon.

How do you think the practice of internal medicine today compares with that during your 36-year career?

There are many changes that have occurred, many for the worst. The government continues to increase their demands and paperwork to satisfy their regulations. There have been vast technological changes such as increased use of MRI and CT scans. I sometimes feel that today's physicians are almost powerless without an MRI or CT. Obtaining an appointment with a physician within a reasonable period of time is much more difficult than it used to be. Demand for their services makes it almost impossible to get an appointment in a few days. Speaking with a physician over the phone is next to impossible. This used to be commonplace. When I went into practice in 1953, physicians competed for patients by providing prompt efficient service. Today I see little evidence of competition.

In my practice I was fortunate to form an association with Dr. Richard Anderson around 1960. We built an office and shared space in it until my retirement in 1989.

___________________________________________________________

1 Leonard's first wife Rachel was a descendant of David Bushnell who devised a submarine during the Revolutionary War and attempted to sink British ships.

2 His second wife Linda was in nursing home administration prior to their marriage. She has four children of her own and five grandchildren.

Reginald (Reg) Fansler was born in St. Clair, Missouri, in 1916. He met his wife Avis in Germany when he was in the Army and she was working in Special Services. They were married for 59 years before her death in 2009. Their children are Marilyn, Susan and Mark, all doing well. Reg spent most of his working life in the Army and retired in 1971 as a full colonel. As a civilian he worked in law enforcement in Georgia and in real estate in Hawaii. He and his family lived in Honolulu for 30 years before moving to Oak Hammock at the University of Florida in 2007. Reg’s 30 plus years of military service span three wars. He first joined the Army in 1937, and he begins his story with what motivated him to enlist then.

From Illinois to the Philippines

My family moved to Illinois when I was a boy. I spent 15 years working on a farm near Greenfield, Illinois. At 17 I graduated from high school and took off. I figured I couldn’t compete with my older brother, so I just left and headed west and worked at various jobs. I had some interest in the military and read brochures about it. One day I walked into an Army recruiting office in Eureka, California. I asked if I could go to Tientsin, China. That’s where I wanted to go with the 15th Infantry Regiment. The recruiter said, “I can take care of that. Just sign on the dotted line.” I did and soon I was in San Francisco. The captain in charge was about 50 years old, like many in the pre-World War II Army which was only about 150,000 in the military at that time. He said, “Sorry, son, only prior service men get Tientsin, China. I said, “What are my options?” He said, “You can turn around and walk out the door. Or I can send you to the air corps in Hawaii or artillery in the Philippines.” I had relatives teaching at the university in the Philippines, so I chose the Philippines and signed on for three-years.

I started my military career on Corregidor Island. I went through basic training and advanced individual training and did the various duties required of me. I was in the 59th Artillery Regiment, coast artillery. Our mission was guarding the entrance to Manila Bay. We had the 12-inch Barbette Cannon, 12-inch Smith 1 and Smith 2 Cannons, and a 14-inch disappearing mortar-like gun. My job was scope operator on the Barbette Cannon.

Impressions of General Douglas MacArthur

I saw MacArthur many times. He was a very distinguished man, always in a white dress uniform. We admired him from a distance. I heard him speak many times in the Rizal Stadium in Manila. We’d stand in formation at parade rest and wait a half hour for him to show up and listen to him speak for an hour or more. He was High Commissioner over the Philippine Islands. He was a fine speaker, but the sun would get pretty oppressive. I think about the third time we heard him speak he got tired of seeing soldiers pass out and fall to the ground. He allowed us to put bayonets on our rifles, stick ’em in the ground and lean on the rifles. That was about the only thing we appreciated him for. (Chuckles)

What do you remember of Philippine culture then?

There were two coast artillery regiments and one regiment of Philippine Scouts, all under the command of the U.S. Army. They were good soldiers and very pleasant people to deal with. They were very competitive in all activities, training, firing range, sports—excellent soldiers. At that time the Philippines was a territory with a president who worked directly with MacArthur.

Did you see any resentment because of U.S. control?

In the north relations between us and the Philippine people were pretty good. Most of the resentment was in the south around Mindanao among the Muslim population; and they’re still fighting today. When we went on leave, the Army always cautioned us about Mindanao. They’d say, “You’re taking your life in your hands in Mindanao.” But in the north everything was peace and quiet.

My last six months on Corregidor I was a corporal and assistant supply sergeant. I was involved in a big effort to refurbish buildings, deal with supplies and renovate the hospital in the Malinta Tunnel. We knew the Japs were coming, no doubt about it. With limited resources we were trying our best to get prepared. The infantry division in Manila would come to Corregidor and practice landings and all kinds of operations. Later when the Japanese attacked Corregidor, our guns couldn’t depress enough to hit the Jap landing crafts. They just sailed under our guns and swarmed onto the island.

I remember in ’39 the battery commander began to show up at reveille. That was unusual. He was trying to persuade us to extend our enlistments. It didn’t work on me. A number of men extended and they’re in a graveyard someplace. They got caught in the Death March. I knew two who survived. One became a master sergeant in the Air Force. The other later turned up as a lieutenant in my MP command. I wish I could recall their names. I remember that lieutenant talking about the Death March: “How to survive!” he said. “Every waking moment was spent trying to figure out how to survive.”

I liked the Army and the discipline and what I learned. Some people don’t like being told what to do, but I didn’t mind being told what to do. I just didn’t want to make a career as an enlisted man. In 1937 I applied to officer training but didn’t make it. I didn’t have enough math and science. Back then you could get an early out, so I decided to leave the Army after 25 months and go back to California. I still had hopes of becoming an officer some day.

Back to the Army and into an MP Unit

When I got out, the Army talked me into staying in the Inactive Reserve. I said, “What’s that going to cost me?” They said, “Just provide us with an active address and phone number where we can reach you, and we’ll pay you $2 a month.” I was working on the Shasta Dam Project in California when I got a letter from the President ordering me back to active duty. That was Christmas Eve, 1940. They’d already been drafting men in ’40. In February 1941 I came back to active duty as a corporal. I was processed at Monterey, California, and then sent to Camp Roberts, California, and assigned to the Adjutant General Headquarters. All I did for three days was run a mimeograph machine. I got tired fast of being an AG slave. So I walked across the street to a Military Police unit where a friend was assigned and asked about joining them. They were eager to get me in the unit. I said, “Let me go get my gear!” This NCO said, “You sit right there. I’ll go get your gear for you.” That’s how I got in the Military Police.

I liked the work. It was active. I was outdoors. A few days after I joined I was told to recruit ten men for the Military Police. I came up with ten stalwarts who stayed with me for many, many months. We learned about the Uniform Code of Military Justice, where authority comes from, how it’s used, how it’s abused. We trained with hand guns and rifles. We didn’t have any training for town patrol and that was our duty. We had a manual that said how to put on handcuffs and fire weapons and how to handle prisoners, but town patrol duties we had to learn on the job (OJT). We had to read the manual and apply it to a town patrol situation, like putting on handcuffs.

Had to read the manual while you were in some joint trying to cuff a guy?

Yes, OJT! I had men with me who were good at maintaining control. Two of them had been state troopers in Roanoke, Virginia. I had a hard time understanding them at first. They used words like ote and abote (Chuckles). I was the duty NCO and I taught them how to apply their knowledge to military situations. They did excellent police work. There was a lot of drunkenness and prostitution going on. Dealing with drunks and fights, routing GIs out of houses of prostitution—we learned all that on our own. I was responsible for town patrol in San Miguel, California, about 2 ½ miles from Camp Roberts. That town had 11 bars. Across the railroad tracks four nice homes had been turned into houses of prostitution.

Were you ever in danger of your life in those situations?

Have you ever been thrown out of a truck traveling 15 miles an hour? I was. Two guys were drunk and I thought I could handle them, but they grabbed me and threw me out of the moving truck. Got scratched up but I wasn’t hurt bad--never had a broken bone in my life. On town patrol you’re always in danger. I remember this training outfit of American Indians. Boy, they couldn’t handle the booze. The Army put out an order that Indians couldn’t drink alcoholic beverages, but other soldiers would pass booze to them under the table. The Indians became very violent when they were drunk.

How many physical fights were you in?

About one a night. You’d run into rowdies and drunks that wouldn’t cooperate. You couldn’t pick ’em up and carry ’em so you had to use special holds. The most effective hold was to lock a man’s arm behind him and move him out. Another effective one was to grab him around the neck and by the seat of his pants and you could march him pretty well.

Were you ever hit in the face?

I never was, but I remember one of my men getting hit with a beer bottle—cut his cheekbone and knocked him down, but he came right up from there. His name was William Fiske, a lumberjack from Oregon—strong, strong! When he put his hands on a man, that man was his.

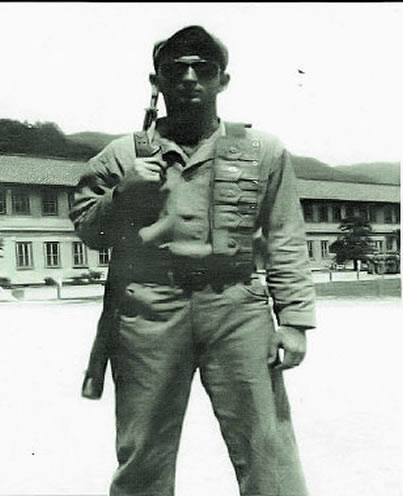

News of Pearl Harbor caused all hell to break loose around us. Sirens going off, vehicles rumbling, troops gearing up, on the move! We were put on continuous duty. They lectured to us on what to do and when to do it. We guarded all bridges, kept all lights out. It didn’t make any difference what you’d been doing before Pearl Harbor, now you had a new situation and new rules you had to follow. Here’s a picture of me as an MP Staff Sergeant.

Dealing with Rowdies and Prostitution in North Africa

I eventually applied for OCS, was accepted, and in December of ’42 I had a short leave before reporting for officer training. First time I’d been home since 1934! I went through OCS at Ft. Custer, Michigan, became a second lieutenant February 26, 1943. I wound up with a company, 438 MP Escort Guard Company. Our mission was to escort prisoners. For a while all we did was train, train, train.

My first overseas duty was in Oran, North Africa. This was 1943. Earlier we’d been whipped almost out of existence at the Kasserine Pass. [General Omar] Bradley had lost almost a whole division. But the Allies regrouped and reconstituted their operations and Mr. Desert Fox [General Erwin Rommel] was defeated. Thousands of German and Italian troops surrendered.

In Oran my outfit was assigned to the Mediterranean Base Section. When I got there, the 1st Division was coming back from the desert. They got billets. We got tents and bivouacked on a hill. (Chuckles) Then the 2nd Armored Division came back from the desert. They were an obnoxious bunch of people, rednecks. They’d roam around at night and throw rocks into headquarters. So a bunch of us second lieutenants led foot patrols to keep the rowdies in line.

Houses of prostitution were in full operation. There were long lines of GI’s going into the houses. The men were processed into the houses on one side and they were processed out on the other side.

How was the processing done?

Army medics made sure their penises were washed and clean going in. Navy corpsmen might’ve been involved in the processing too, I don’t recall.

How about going out?

They might’ve used a syringe and shot something up the penis, but I’m not sure of that. They were processed going out, I’m sure about that—military regulations. By the time I’d gotten to Oran the second time, Eisenhower had put all the houses of prostitution off limits. Then MP’s had to make sure GIs didn’t go in there. We roamed the halls of the houses checking to see if soldiers were there, and if they were we routed them out. Those houses were exquisite buildings, beautiful tapestries, beautiful carpets. In Oran there’s a long beautiful coastline and a beach. Part of the beach then was the Nurses’ Beach. After the houses were put off limits, everybody tried to figure out a way to get to the nurses. Fortunately, there weren’t many violations. Men were busy processing, moving out to Italy. They didn’t have much time to fool around.

Handling German POW’s

My most challenging job was handling German prisoners. We’d pick them up at collecting points and shuttle them to La Stina [sic] Air Base.* They were the remnants of Rommel’s Afrika Korps. They were loaded onto ships and sent to the U. S. Each ship carried 500 German POWs. They were put in the holds of the ship and allowed to come out one or two at a time to go to the bathroom. We had to make sure they used the leeward side of the ship or it would get messy. They had buckets to use if they didn’t want to come out. We had to make sure we had enough supplies and water for the crossing. A big challenge was determining how many potatoes we needed. Those Germans loved their potatoes. My POW ship was the same one I came over on: the USAT Borington Queen. [sic] *

We had pretty smooth sailing, 100 plus ships in our convoy. We were protected by our warships and submarines. We’d sail this way and that way and that way and this way so as not to be targets for German U-boats. Patton’s people had captured an Italian Major General and his staff. They were senior officers assigned to my ship. We were told to put them in a nice suite.

I wonder if the Italian general was Giovanni Messe. Messe surrendered German and Italian troops to the Allies after Rommel got sick and returned to Germany.

He may have been, but I don’t think so. Seems the one I had was from Palermo. I was still a second lieutenant. Every morning this Italian general gave me list of things as long as a maiden’s prayer.

How did you deal with prisoners on ship?

With a hard-nosed attitude. I told them what to do and they did it. I didn’t have any trouble with them. I had a German interpreter by the name of Walthemathe. He was a well-educated enlisted man, university graduate, tall, good physical specimen. He dictated my edicts to the senior German NCO and everything worked out fine. We shipped over to Newport News, Virginia. I got a ten-day leave, went to New York, checked into the Commodore Hotel and made myself comfortable. Then it was back to Oran, North Africa.

After my second tour in Oran, I was separated from my unit and sent to the German POW camp at Camp Hearne, Texas, not far from Texas A & M University. I spent six months there assigned to a headquarters company. My job was Defense Counsel for American soldiers being tried for various infractions. After that I was ordered to take a cadre to Camp Joseph T. Robinson in Little Rock, Arkansas. That camp held 21,000 German prisoners. This was 1944.

There were various POW sites in Arkansas. I took 360 Germans to one in Crawfordsville, Arkansas, about six miles from West Memphis. Facilities were built including separate mess halls for us and the Germans and a guard tower. Germans ate pretty well in our camps, lots of hamburger and potatoes. We even made special lunches for the Germans selected to work in the fields. They consisted of spam, baloney, peanut butter and jelly sandwiches. The farmers in the area had no labor but women and children. Many Germans worked the farms. I had a contract with a number of farmers to provide them 300 working bodies six days a week.

Challenges in Korea