|

James (Jim) Gilmore and his wife Sara are founding members of Oak Hammock at the University of Florida. Jim Gilmore served in the Army of Occupation (Japan) and later as an officer in the U. S. Navy Reserve from which he retired. On January 30, 2010, I interviewed him in Oak Hammock’s Meditation Room, a day later by phone, and some by e-mail.

The military for me started when my father was recalled to the Army in 1942. He served as an intelligence officer with a B-26 squadron in England. A few years later, I enrolled in the University of Cincinnati in a special program. I was able to substitute my senior year of high school for my freshman year at the university. This gave me a leg up on many 18-year-olds, and I was accepted into Officer Candidate School at Fort Knox. However, they changed the rules. If you accepted your commission, you had to stay in the Army four years. This didn’t agree with the plans of many of us and about half the class dropped out without a commission.

Impressions of General MacArthur

I was drafted into the Army and served from the spring of 1946 to the spring of 1947. My college background helped. I was assigned to General MacArthur’s Headquarters in Tokyo and worked in Headquarters and Service Group. We were in charge of all the American post exchanges and service clubs in Japan. I was assigned to the Tokyo Kai Kan Hotel, a modern European-style hotel. It was one block from MacArthur’s Headquarters. MacArthur and his staff had taken over the Dai-Ichi Insurance Building. I could look out my window in the Kai Kan Hotel and see MacArthur get in his black limousine with an honor guard. I think he had the honor guard to impress the Japanese more than anything else. MacArthur and his family lived on the American Embassy grounds. I saw them occasionally. He looked imperial and acted imperial.

There was no doubt about MacArthur’s abilities as Supreme Commander of the Occupation of Japan. He did a superb job. He knew Japan well. He knew there was no sense in trying Emperor Hirohito and his court as war criminals. He used the emperor to placate the Japanese. They did whatever the emperor told them to do. The emperor told them to stop fighting and they did, completely. There was absolutely no resistance from the Japanese. GI’s went into Japan with MI rifles and officers with side arms, but we didn’t need the weapons. We were completely safe. We made an armory in the hotel basement and put all the weapons down there. A former Japanese marine was hired to take care of the armory. Like other Japanese, he was very happy to have a job.

What was your job in the hotel?

I started out as a desk clerk and eventually became GI manager of the hotel. The hotel was quarters for American officers, company grade and field grade. There were 700 Japanese employees, including a number of Nisei who were Japanese/Americans. They spoke English well. Some Nisei had been trapped in Japan during the war. Others fought with us in the war. My superior in the hotel was Lieutenant Art Hiraga. He was born in California and had fought in the Italian campaign. His unit [442nd Regimental Combat Team] was the most decorated military unit in American history. My job was to find out what our officers wanted and then get the Japanese workers to do it. The Nisei were a great help in this regard because of their bilingual abilities and knowledge of American ways. There were many cute little Japanese waitresses working in the hotel. They giggled a lot, especially when we photographed them.

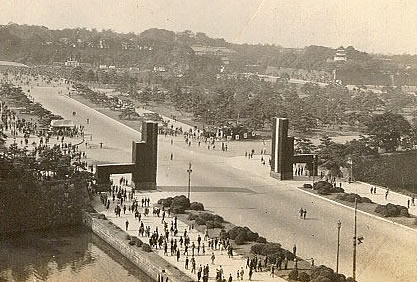

Here are some pictures from those days. The first one is of the Kai Kan Hotel taken over the palace ground moat. The Dai-Ichi Building, MacArthur’s Headquarters, is the building to the right, partly behind the overhanging willow branch.

The Emperor’s palace grounds are an extensive area, across the street from the hotel. The picture above (right) shows the entrance to the palace grounds. It’s an immense area, about 20 square miles.

The man in this picture is with my friend Terro, a bell boy. The woman in this picture with me is Yesko San, a hotel waitress. They were both in their mid 20’s

The “Magic Carpet” and a Geisha House

I got promoted because my superiors went home. I was on the outbound “magic carpet.” Most of the combat troops were going home, and we draftees were sent to Japan to replace them. I made corporal and could have made sergeant, but the Army froze draftees’ rank. All draftees were to be discharged. I felt like a tourist in uniform. (Laughs.) So did a lot of GI’s. We could get in jeeps, travel the countryside and go sightseeing.

One time I was invited to a Geisha house by the Japanese management. The Geisha houses were not places of ill repute. The Geishas were high-class women schooled in the arts and fine entertainment. We sat on the floor and listened to them sing songs and play stringed instruments. They served us tea. The food was cooked on a charcoal burner. The only American song the Geisha ladies knew was “You Are My Sunshine.” I was able to talk with one of them. She spoke pidgin English and I knew a little Japanese. The Geishas were very graceful and charming.

In the states during the war there was a lot of hatred toward the Japanese. When I got to Japan, I didn’t know what to expect of the people. It turned out the Japanese weren’t the monsters I thought they’d be.

Destruction in Tokyo

Our planes had fire-bombed Tokyo and destroyed many wooden buildings. There was devastation everywhere. Here’s a picture showing part of the destruction.

Many people were living in makeshift structures. Cleaning up and building was going on all over the city. The Japanese made scaffolding out of bamboo. Guys were scurrying up and down the scaffolds working hard to rebuild. I was impressed with how industrious the Japanese were. They are physically attractive people, very courteous. They smile and bow a lot out of courtesy. They were very good at taking orders.

A friend of mine needed to install a flagpole. He got a Japanese man to dig the hole. My friend had to do something else and temporarily forgot about the hole. When he came back later, the Japanese was still digging. He’d dug so deep he was out of sight down in the hole. He didn’t know what the hole was for; he was told to dig a hole; he followed orders and kept on digging. (Laughs)

Did you see or sense any hostility toward Americans?

The feeling I got from Japanese I knew was that the war was over, and they had to rebuild their lives and country. They wanted to make a peaceful transition and build a new Japan. I went several times to the war crimes trials. You could get a pass and sit and watch the proceedings. They were pretty boring. I saw Tojo slumped in his seat. He looked like an old man half asleep. He knew he was at the end of his rope. The whole thing was like the war-crime trials in Germany. It was a foregone conclusion that Tojo and others on trial were going to hang.

Tony, the Wheeler-Dealer

I knew this fellow named Tony. Not sure of his last name. He was discharged in Japan and got a government service rating. The reason he wanted to stay as a desk clerk was to operate his money exchange. He’d get cigarettes from his buddies in the PX and sell them to the Japanese. He’d take the yen and convert it to military currency. Military currency then looked like monopoly play money. Tony would swap the military currency for greenbacks. I’m sure MacArthur would’ve frowned on this sort of thing if he’d known about it.

What service decorations did you get?

The World War II Victory medal, Army of Occupation medal, and Good Conduct Medal! There was a saying about the Good Conduct Medal: “I was alive in ’45.” There was a similar saying when I was in the Navy Reserve. “I was alive in ’65." Everybody got the Good Conduct medal.

In my Army days, I knew two guys who didn’t. They screwed up big time. (Chuckles.) I’d appreciate hearing some highlights of your career as a Navy officer.

In 1950 I graduated from the University of Cincinnati with a degree in mechanical engineering. The same year I was commissioned an officer in the Naval Reserve. I went to destroyer school. There were five destroyers assigned to our reserve group, all in Tampa Bay. I served as Engineering Officer on the USS Coolbaugh and USS Greenwood. In 1961, I was recalled to active duty. It was a shock having to leave my civilian career. I commanded the USS Tweedy and USS Darby and served as Prospective Commanding Officer on the USS Beatty.

We operated as school ship for the fleet sonar school in Key West. We’d do figure-8’s over a submerged submarine to train sonar men. We were told there were Soviet submarines off our shores, but we never spotted any. In 1980 I retired from the Naval Reserve with the rank of captain.

Eli Graham, Jr. was born and raised in Starke, Florida, and now lives in Daytona Beach, FL. He and his late wife Gloria have two children and 15 grandchildren. In 1944 he was drafted into the Marine Corps and trained at Montford Point, North Carolina, then an all-Black basic training post. He went on to serve on war-torn Guadalcanal, Peleliu Island and Tinian Island. I interviewed him by phone on January 24, 2015.

I was in the 7th Ammunition Company. Had 8 weeks basic training at Montford Point. Got all kinds of training in weapons and demolitions: M-1 rifle, BAR [Browning Automatic Rifle], .45 pistol, hand grenades. Montford Point was segregated, close to Camp Lejeune where the White boys trained. Montford on one side, Lejeune on the other side. We didn't have officers--sergeants and NCOs, highest ranks at Montford Point. Later on President Truman gave the order said Blacks could be officers. We got rifle training on the Parris Island rifle range. They shipped us to Guadalcanal for heavy weapons training, machine guns, mortars. Spent a month on Guadalcanal. Japs still there, sniping at us. They had to be wiped out.

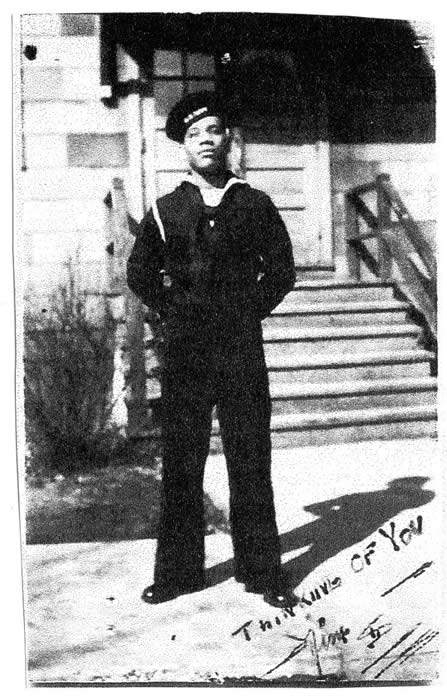

Eli Graham, Jr. U.S. Marine Corps, ca. 1944

At the time how did you feel about being a segregated Marine?

We had no choice. We had to take it. We were trained to go fight.

What was the situation when you first hit the beach at Peleliu?

Oh man, it was somethin' else. First Marine Division hit the beach, all of us together, Blacks and Whites. Japs were waitin' on us. Lots of guys didn't make it, just didn't make it. Guys all messed up, arms missin, some blown to pieces. We were scared to death. I was in the second invasion group. Navy planes came in and knocked out Jap machine guns, softened up the beach.

We carried ammunition to front-line Marines. Took casualties back on stretchers--lots of casualties! We had to get the wounded back, then go out there and bring back the dead. Japs shootin' at us! We had to lie them stretchers down and hit the dirt. We were all young and scared to death.

How did you deal with the fear? Did you pray?

Oh yeah! Said regular prayers my father taught me: "Our father who art in heaven." There was a new prayer, but I always prayed the old one. My father was in World War I. I had a grandson in Parris Island and a daughter in the military.

Did you ever fire your weapon in combat?

So many White guys casualties, the 7th Ammunition Co. was ordered into combat. I shot at Japs. Don't know if I hit any, didn't have time to check....

Editor's Note! Unfortunately, phone trouble cut short my interview with Eli. Unable to reach him again by phone, I contacted Sean O'Dwyer, a military historian and a history major at the University of Florida, who had video-taped Eli's story of his war experiences. Sean gave me the following information:

* Eli said that late in the Peleliu campaign he got a shrapnel wound in the right leg, and he switched places with another Marine to go and receive aid. He is disappointed that the wound is not on his service record. It would have qualified him for the Purple Heart.

* He left Peleliu in October 1944. He was on Tinian Island at the time the atomic bombs were assembled and put in pits.

* He was discharged with the rank of Corporal on March 6, 1946.

* He is proud to have the same birthday as the U.S. Marine Corps, November 10. On this date in 2015 he will be 90 years old.

Sean and I are most grateful to Eli Graham for his story. During World War II, Eli and many Black Americans served under fire and made solid contributions to Allied victory. Their service is all the more commendable because it was done for a nation that at the time denied them full civil rights. Their sacrifices and courage in some of the war's bloodiest battles are truly heroic.

James Lincoln (Jim) Greene

(As Told by His Son, David M. Greene)

My Dad was born and raised in the university town of Madison, Wisconsin (Dane County). He was an outdoor type of guy all his life. As a youngster he played ball, rode bikes, rode horses, and enjoyed fishing, swimming, roller skating, ice skating, hockey and sledding. When forced to be inside, he filled his free time building model airplanes and avoiding his older brother and sister. As kids they spent most summers living with either of two great aunts. One had a large farm in Grant County; the other ran a roadhouse outside the Madison city limits that featured steak dinners. Across the highway from the restaurant was a private airport where when done with chores Dad was allowed to visit. The "royal" personnel tolerated this young black boy around the hangers and occasionally gave him rides. There he further developed his love of airplanes and the desire to become an aviator when he grew up.

Madison in the 1940's had a population of around 40,000 but only 2% black residents. The schools were integrated and the Greenes attended West High School via city bus or bike. Each was the only black in each class and was usually ignored. Occasionally, they suffered the humiliation of being called names like "nigger" or "blackie." The boys got into fights, but their sister just cried. Dad and his brother George Jr. were excellent athletes, however, and they thrived in sports and became welcomed teammates.

When World War II broke out they were too young to be drafted, but by 1948 Dad followed his brother into the U.S. Navy after graduation from high school. He hoped to eventually be trained as a naval aviator. He entered service at the Chicago Great Lakes Naval Training Station, survived boot camp, and was attached to the aircraft carrier S.S. Roosevelt, Fleet Air Squadron 5, out of Norfolk, Virginia. Because of his race, he was denied flight training and was assigned to the support staff aboard the carrier. Allowed to enter boxing competition, he became the undefeated middleweight champion of his naval fleet. Dad said, "This was one way I vented from the frustration of being viewed as 'second class' or 'ineligible' for everything I wanted to do for no other reason than my color."

Dad did count among the valuable things he learned in the Navy were discipline, character development, perseverance, and patience. He was very disheartened by how blacks were treated in the South and especially how black men were always expected to be submissive and to avoid controversy or retaliation.

James (Jim) Greene during Naval training, ca. 1948

After his honorable discharge, college, marriage, and a successful career path in Wisconsin state service, Dad (with Mom's support) attained his private pilot's license with aerobatic training. He owned and briefly operated Airpool Travel International as a hobby of sorts.

Dad inspired me to go into aviation at age 16 (and help fulfill his dreams). He helped develop a Madison Urban League PAL Program which introduced us local black youth to aviation. He was a member of the Negro Airmen's International Chapter of the Tuskegee Airmen. Those membership activities further led me to choose aeronautics as my field after high school. Mom and Dad financed my initial flight training in Alabama under the great pioneer Chief Anderson who trained the famous 99th Fighter Squadron (these were the Tuskegee Airmen, the all-black segregated unit that performed spectacular service during the war). Under Chief Anderson I also learned the history of earlier "unknown" famous flyers, like George Taylor and Janet Bragg. C. Alfred (Chief) Anderson ((1907-1996) was known as the "Father of Black Aviation," Captain George Taylor (1919-2008) flew 100 combat missions, and Janet Harmon Bragg (1907-1993) was the first African-American woman to hold a commercial pilot license. Here are pictures of them at the height of their aviation careers (taken from Wikipedia).

Chief Anderson George Taylor Janet Harmon Bragg

The experiences and excitement I shared with my Dad led me to take more training at the Gateway Technical Institute in Kenosha, Wisconsin, 1980-1981. At age 53 with 7,000 flying hours, I am now the Director of the Bureau of Aeronautics in the Wisconsin Department of Transportation. It is very satisfying to follow in the footsteps of all the black pioneer pilots who fought both gravity and racism along the way to make their mark in aviation history.

My Dad died at age 80 at Oak Hammock at the University of Florida from the insidious disease of Alzheimers. He and Mom were among this community's founders in 2004. On Valentine's Day 2010 he wrote to my Mom (his wife of 60 years) this note: All I'll ever need is you. You are my life and soon you will see, I'll love you forever with all my heart throughout eternity. By May he couldn't speak and on December 19 he passed. He was an active dedicated AME Methodist and attended UW Madison majoring in mechanical engineering and minoring in computer science. His civilian employment included statewide 911 Program Coordinator for the Wisconsin Department of Administration until retirement in 1985. He was also co-founder and Executive Director of the National Emergency Number Association charged with implementing 911 nationwide.

Fred and Patricia (Pat) Harden are native Floridians, now residents of Oak Hammock at the University of Florida. With their scientific backgrounds (Fred in entomology, Pat in Biology) and through their leadership in numerous environmental organizations, Fred and Pat have contributed much to environmental and ecological progress in Florida. Fred was a founding member of the Florida Chapter of the Nature Conservancy. Since 1973 Pat has served in various offices on the Chapter's Board of Trustees, including the presidency. Fred and Pat grew up during World War II and have vivid recollections of German submarine attacks off the Florida coast and other happenings during the war. Fred also recalls some of his tense times during the Cold War.

Fred: Watching German U-Boats Destroy Ships Off the Florida Coast

I think it was in the summer of 1941. I went every day to swim off Palm Beach. There was an Army Air Corps base near there called Morrison Field. I looked out from the beach, and I believe it was a British freighter went by and a German submarine surfaced and began to shell it. I heard they tried to call Morrison Field for help. The U. S. was not at war, so American officials had to go through a whole process to get Washington's approval. By that time the sub had submerged again.

Later on, it was not unusual for us to see burning tankers offshore that had been hit by German subs. I saw a lot of oil floating in. German subs sank ships all the time. You could see 'em burning at night. I didn't see any bodies, but I know they were there.

Before the war and even after the war started the Coast Guard didn't have watchtowers on the beaches. For about three to six months there, a submarine could come in at night and use the shoreline lights to spot a ship and blow it away. The Germans had a name for this, meaning why is the American coast lighted, but we'll take advantage of it.* They sank tons of good ships. I'll never forget watching three or four ships burn like that. Pat was living at Ft. Pierce then and also remembers seeing burning ships hit by German subs. The Coast Guard tried to rescue people, but a lot of tankers you couldn't get off them very well. There were some bombers over at Morrison Field, but whether they could've done any good, who knows! Try and drop regular bombs--that wouldn't work very well with submarines.

Later we had blackouts, and the Coast Guard put up watchtowers. Palm Beach had one every mile or so and there was somebody on them looking for ships. My father was too old for the war, but after it started he was one of the volunteers for the Coast Guard Auxiliary. They had depth charges, but they never used them charge, because if they dropped a depth charge and didn't go fast enough, it would've blown them out of the water. The Coast Guard had a horse patrol and they'd use polo ponies. They'd have .38 pistols and ride polo ponies at night looking for saboteurs--you know saboteurs were caught in Jacksonville early in the war. My father said a horse could tell when sharks came up close to the beach. Horses could detect that somehow--I don't know how.

When my dad was riding horse patrol, the Germans sank a rum ship off shore. A 50-gallon wooden barrel of uncut, illegal rum floated ashore. He buried it in the sand and came back and got it. (Laughs) He had a gas station and cut a hole in the wall and took that barrel of rum and put it in the wall and sealed it off and put a spigot on it. 190 proof rum, you know, it'd knock you on your butt! (Laughs)

Were you scared when all those ships were getting blown up?

No, not particularly. When you're 11 or 12, 13, you know, you don't worry about those things.

What did your parents tell you about the war, how did they react?

Toward the end they said we have to worry about the Russians. They're the ones we're probably going have to do battle with. In World War II I had five or six cousins split up between the Army Air Force, Army, Navy, and Marine Corps and mostly all of them got back.

[*Editor's Note: During this time the Germans had two names for their U-boat success against unprotected ships: Das zweite Glückliche Mal (the Second Happy Time; the first was in 1940-41 when U-boats were destroying shipping in the North Atlantic) and Amerikanische schiessende Jahreszeit (American shooting season).]

Pat: World War II Memories

My family moved to Fort Pierce, FL on the east coast in 1940. I started first grade in 1941 and remember how concerned my parents were on hearing the news on December 7 and the avid reading of the newspaper on December 8 that bore the big, bold headline JAPS BOMB PEARL HARBOR. It was the beginning of many childhood memories in the ensuing war years and the aftermath. Some of these come from hearing adult conversations and some are first-hand experiences.

The U.S. Navy took over both of our beaches for training Underwater Demolition Teams (UDT) one of two bases on the east coast of the U.S. I believe these UDTs were the forerunner of the Navy’s current S.E.A.L. teams. Our south beach was built up with barracks, officer quarters, a hospital and other military infrastructure. The town filled with servicemen. Women of “good reputation” did not go alone into our small town on Friday and Saturday nights!

I recall having the windows of our house rattling as explosive devices were detonated during the training sessions. Our homes had black window shades that had to be pulled as soon as a light was turned on. The top half of car headlamps were painted black to keep the light beams from reflecting skyward.

Ration stamps became the norm with housewives trading with each other for butter, sugar and other rationed commodities. Gas stamps were a necessity for the breadwinners. Margarine back then was just lard with a food coloring packet you mixed in to make it look like butter. It became the norm.

Of course, air raid and fire drills were conducted at school (we only had one school) where we all crawled under our desks and/or marched outside in orderly fashion. As the war wore on, the school participated in the “Junior Commando (JC) program”. This program encouraged students to collect scrap metal, lard, and aluminum foil (back then there was no aluminum foil in rolls) from candy and gum wrappers, cigarette packages, etc. Depending on how many pounds of these “vital” materials one collected, you received awards: a JC “army” hat, sweatshirt, jacket and so on. We took it very seriously in grade school and were very proud of our “uniform” pieces! I remember wearing my JC hat and with friends, marching along and chanting some ditty with the chorus of “We’ll go Sieg, heil, sieg heil, right in the Fuerher’s face!” The “razzberries” were given after each “sieg heil.”

Most young men in our town went off to war and, like in many other towns, some never returned. Sadly, toward the end of the war, I recall hearing the news of a cousin who was a fighter/bomber pilot being MIA in a bombing run over France. Later, the news came that he had been shot down and killed on the mission.

My mother was a Red Cross volunteer at the hospital. She often came home with stories of young sailors she visited at the town hospital (the base hospital was small and often full) whose bodies were so inflamed and their eyes swollen almost shut from being covered by sandfly (no-seeum bug) and mosquito bites. This happened to them on night maneuvers on the beaches. There was basically no mosquito control at that time (not until DDT). Early in the war, there would often be men who had been badly burned when their ship was torpedoed by the Germans. My mother would say, “I felt so bad I wanted to cry; they are just young boys and in such pain.” Many, she was sure, were to be scarred for life.

We spent part of our summers in Juno Beach, then just a few cottages and one motel. We had to be off the beach at sunset and could not return until after sunrise. The beach was patrolled by Coast Guardsmen on horseback with German Shepherd dogs. One night, we heard an explosion and watched a tanker burn that had been fired on by a German sub.

There was a story going around that on a captured U-boat the military had found two tickets to a movie theatre in Miami and a Merita bread wrapper. I don’t know if it was true but, it was known that Germans had come to the mainland along the coast.

One of my uncles was in the Army Air Corps and was stationed in England as a radio operator. He would send me C-Ration kits on occasion and I would try to eat some of the food…yuk! The powdery, “chocolate” bar was about the only thing I could stomach. There was a package of two or so Camel cigarettes in each kit he sent. I did not try those. The kits were in heavily waxed cardboard. I can understand why our servicemen were so happy to get a home-cooked meal.

On a lighter note, the military formed inter-service football teams and the Navy in Fort Pierce participated. The public could come to the games and they were played at our school football field. Johnny Lujack was the local Navy quarterback and the team won the championship. I loved football and Johnny became my hero. The base commander lived in our neighborhood. He arranged for my dad and me to meet Johnny after practice one day. I received an autographed 8x10 photo and football! I was the envy of my fellow football playmates. Lujack went to Notre Dame after the war and was their starting QB, winning the Heisman Trophy in 1947. I kept a scrapbook of him through all of his Notre Dame years!

My mother and I used to ride the train to Miami to visit her folks, my grandparents. The trains were always crammed with servicemen because Florida had many military bases and we were often seated across from them. I don’t remember exact conversations, but they were always very nice to us and I looked forward to those trips because they offered me gum and candy!

During the war and for several years afterward, my dad would always stop and pick up hitch-hiking servicemen. The little town of St. Cloud, FL named a street for every one of the forty-eight states and it is said that any serviceman hitching through the town could knock on the door of almost any home on his “home state street” and get a free meal and bed.

Sunday morning April 12, 1945 I was coming home with a friend and we heard on her aunt’s car radio that President Roosevelt had died. I told my parents and they were incredulous as they had not listened to the radio that day.

Even at my young age, I remember the feeling of patriotism and pride in our country. It seemed we were all pulling together for the common good and supported the war effort. Yes, there would sometimes be grumbling or stories of “cheaters” and draft dodgers, but on the whole the citizens of the U.S. seemed united toward the common goal. My parents clustered around the radio for each of President Roosevelt’s Fireside Chats. We kids watched with rapt attention when the newsreels came on at the movies during Saturday matinees. We wanted to know how the war was going, how the troops were faring. We learned about parts of the world we'd never seen, the vagaries of human nature, and the danger of prejudicial hate as we saw the horrors of the death camps and the Bataan march. It was a time that will forever live in my memory.

Fred: Memorable Experiences During the Cold War

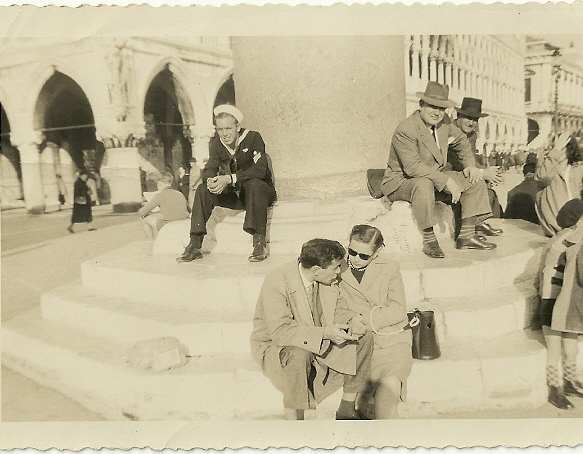

In late November 1951, I was a seaman Quartermaster striker on board the USS Willard Keith DD775. We were on a six-month cruise attached to the 6th Fleet. In September we had left our home base of Norfolk, Virginia, headed for the Mediterranean Sea with good will stops at the ports of Gibraltar; Augusta Bay, Sicily; Naples, Venice and Trieste, Italy; Leros, Greece; and Istanbul, Turkey.

During most of these visits we were operating by ourselves. I wondered why, but did not find out our true mission until we again entered the Atlantic Ocean.

Fred Harden's ship: Willard Keith DD775 near Venice, Italy, October,1951

Fred in Venice as part of a U. S. Navy good will tour, October 1951

At this point, we headed back toward Gibraltar, carrying out exercises with the 6th Fleet till we were about to enter the Atlantic Ocean. We were planning to extend our good will tours to include the ports of Bordeaux, France; Bremerhaven, Germany; Copenhagen, Denmark. And then on into the Baltic Sea to visit Bornhorm Island, which belonged to Denmark, but lies off the Polish coast.

Then we were given different orders in November that said we were separate from the 6th Fleet and were assigned as a small unit of the Northern European Force, operating in the company of the USS John W. Weeks DD701. Both of our ships were Allen Sumner Class Destroyers built in 1944.

Tense Time with a Russian Submarine and a Heavy Cruiser

Now some of us realized we might be going into harm’s way because the quartermasters and bridge officers were told that we had a secret mission, that we were to track Russian shipping and to monitor Russian radar at every opportunity.

The visit to the Baltic Sea was critical to our true mission. It was during this time in the Cold War that the Russians were shooting down our aircraft along this zone in Europe. The aircraft were mostly modified B-24s that among other duties they were doing the same mission we were undertaking. To my knowledge none of those air crews were ever heard from again. I hope I am wrong in this part of my story.

We knew that the Russians knew of our purpose, for they assigned a submarine and a heavy cruiser to follow us to and from on our trip to Bornhorm, Denmark. This began almost as soon as we left the Kiel Canal and entered the Baltic.

It is hard to explain the feeling we had going through the Kiel canal. Here we are traveling through dairy country in a 378-foot warship and are surrounded on both sides by peaceful dairy cows and farm houses. A contradiction in values, which also made those who were lucky enough to view it feel like we were back in the states and not on some military mission.

If my memory is correct, we were on General Quarters a good deal of the time. Of course we were all gung ho, we had a great Captain, a well-trained crew, and the best gunnery in the 6th Fleet. As you know, there are few secrets on board a ship that has 350 men on a ship only 376 feet long and 40 feet wide. The Russian submarine and the Willard Keith made practice runs against each other. I hoped all parties knew it was practice, but it could go ugly if something went wrong during these runs. I did not have access to the data our ship collected. I knew the ET [electronics technician] who was the snoop, but he was classified and said nothing. We did attempt to ID Russian shipping, but I don't know what was done with the data.

The Russian heavy cruiser stayed on the horizon, but with its 8-inch guns we could be in a bad way if things didn’t go well from the Russian point of view. But we were well armed with

- 6 - 5in .38 guns

- 12 40mm AA guns

- 11 20mm AA guns

- 10 torpedoes

- 6 depth charge projectors

- 2 depth charge racks

Our only back up was a small torpedo boat back in Bremerhaven. I’m sure that shooting down a aircraft that is pushing the limits of international borders is one thing, but taking on a well-armed warship in international waters is another. I feel both sides felt that way, but one over gung-ho person on any of the three ships could have set off a really bad scene, from which we would have been the loser.

Fortunately all went well and the Keith returned to Norfolk, Virginia, in February 1952, after visiting Plymouth, England and Derry, Ireland. On this cruise we had an adventure with a hurricane in the Bay of Biscay off the southern coast of England half way to Gibraltar.

Surviving a Violent Storm

In December 1951, the Willard Keith was on a six-month cruise with the 6th Fleet and had just left Gibraltar on our way to Bordeaux, France, as part of our good will visits during the Cold War. To get to Bordeaux we had to venture out into the Bay of Biscay which is noted for terrible weather any time of the year.

About the second day the barometer began to drop like a stone and the wind began to pick up. In 1951 there were no weather radar systems much less weather satellites. It seems we had sailed into what was left of a hurricane making its way toward England and the North Atlantic. The normal way to estimate sea conditions is by the table on the Beauford Wind Scale that gives the sea state. For example, Beauford Scale 11 says that "Wind is 56 to 60 knots. Expect exceptional high waves, nearby ships may disappear from sight. Everywhere the sea is heavy and shock like.” According to the Beauford Scale, we were at the maximum level 12 with winds in excess of 65 knots “where the air is filled with foam and spray. The sea is completely white, with driving spray and visibility is very seriously affected.”

Our weather had gone from bad to terrible. The sea began to rise to about 40 to 60 feet wave height. The waves came on like mountains and caused our ship to ride up at a steep angle then crash down into the trough between waves during which 1/3 or more of the ship disappeared under green water. Our ship’s bridge or pilot house is normally high above the water, but when those waves closed over the ship we in the bridge would at times be covered with water on all sides.

The ship’s deck developed a crack which began putting sea water in a crew’s sleeping compartment. Of course the crew went in to rescue their dress liberty blue uniforms. Forget the other things in their lockers! The ship was taking a real beating. We were only 376 feet long and 40 feet wide into which were crowded a crew of 350 men. We were rolling up to 55 degrees in each direction. I have no idea what the angle was in the rising and falling between waves. All of the ship’s life-saving gear, life rafts, and rescue floats disappeared in the waves. The motor boat was lashed down and was safe. However, one of the two twin 5 inch gun turrets were beginning to come loose from the main deck.

At this point no one wore life jackets. In this sea condition you would not survive very long in the cold water and the ship would be unable to turn back to your location. That was us in a nut shell.

We had to use our twin-engine props to help keep the ship turned into the wind, for the rudders could not handle the seas and wind alone. At this stage FEAR took over and seasickness of the crew began to disappear. Fortunately, I don’t get seasick and tend to love rough weather. To some of us it was exciting and you began to understand the power of the sea, but it was slowly beginning to tear the ship apart. Metal posts and hatches were being bent and broken. In this kind situation, you have a job to do. Your mind's not on fear but doing your job the best you can.

Our Captain, Commander Leslie O’Brien, made a decision that we could not last long in these conditions and made a run for the shelter of the harbor at Bordeaux, France. You may recall in World War II in a storm of this magnitude in the Pacific, three destroyers capsized and lost almost all their crews. That was on our minds although well hidden. There was a problem trying to go into a harbor during a storm, Bordeaux’s harbor entrance had a depth of 19 feet, and our draft was 16 feet. In between waves we might bounce off the bottom.

The Captain called to set the “special sea detail.” This meant I had to go aft through the ship to get my station in After Steering, the last compartment at the stern of the ship. I and two other water rats got back there somehow. Our job

was to steer the ship from there in case of loss of power or if the bridge was knocked out due to combat damage.

There were two electric motors which turned the two rudders under normal conditions. If we had to take over steering due to a power loss, the two seamen would use hand cranks to turn the rudders, while I would be facing the stern looking at an overhead compass and begin steering with a small steering wheel.

As luck would have it, as we entered the harbor in heavy rolling seas, we lost steering power on the bridge and we rolled over on our beam and entered the harbor sideways. There were stories that we took water and rocks down our smoke stack because we rolled over on our beam ends, but that might have been just a good story to tell from the engine room guys' point of view. So there I am standing or trying to stand in ankle deep water, urging my guys to ‘CRANK AND CRANK SOME MORE’, all the time trying to see the compass in the poor lighting given by emergency lights. As soon as we got her turned back in the direction of the harbor, the power came back on.

While all this was going on, I still had contact with the bridge through my head phones. I asked them what was the metal noise I had heard over our heads on the main deck? Their answer was “no problem, just a loose depth charge, but don’t worry. It is not armed.” After we tied up we got news that as many as 150 fishing boats were missing and assumed to be lost at sea.

Disaster Hits the SS Flying Enterprise

The crew assumed we would be in port for a while to fix the storm damage. I believe some of them got a day’s liberty only to find out we had to turn around and go back out to sea on a rescue mission. The SS FLYING ENTERPRISE, an Isbrandtsen Company passenger/freighter, was in trouble off shore between France and England. Off we go back out to sea. Fortunately, the wind had dropped from hurricane force to only gale force. We understood that the passengers and crew had been taken off by a US troop ship and a freighter, but the captain stayed on board to protect the cargo from salvage efforts.

We arrived the next day to relieve the USS JOHN W. WEEKS DD 701, which was low on fuel. The seas had dropped quite a bit and our Captain notified Captain Kurt Carlsen by radio that a number of our crew had offered to go aboard to shift cargo. The FLYING ENTERPRISE was beginning to develop a list of a least 40 degrees. Captain Carlsen declined any assistance. He wanted to wait until two ocean tugs hired by his company came to take him under tow.

As soon as the hired tugs arrived and began towing the FLYING ENTERPRISE in the direction of Falmouth, England, about 300 miles north, the weather began to worsen with another storm on the way. Waves begin to increase, which gives our ship all kinds of grief. We are cruising in a circle around Carlsen and his ship at the slow speed of 5 knots, which causes us to roll back and forth at least 20 degrees each way, very uncomfortable, since it is a slow roll and nothing stays put.

A crew member, 1st mate Kenneth Dancy, from one of the tugs jumped from a tug to the FLYING ENTERPRISE when the two ships banged together. He was able to help secure tow lines. Later a second storm hits and the tow lines keep breaking and we are now only about 30 miles from safety.

The next day the storm got worse. Now the FLYING ENTERPRISE had listed to the point that her smoke stack was almost level with the higher waves. Captain Carlsen knew he would lose his ship and called one of the tugs to come up close to the stack, at which point he and 1st Mate Dancy calmly stepped off into the sea and were quickly picked up.

I had the watch when the ship finally turned her bow skyward and slowly slipped beneath the sea. Just before the bow went under, a number of flares fired off on the bow and ships nearby blew whistles and horns which gave the FLYING ENTERPRISE a good send off on its way 280 feet to the ocean bottom.

My entry in the log recorded the exact time of her sinking, and location on the chart in latitude and longitude. I could not enter my emotional feelings of the loss of the ship and especially the loss Captain Carlsen must have felt when she finally sank. Sailors seem to have a special bond to their ship. It's difficult to explain to people who are rooted to the land. I think a number of us had a tear in our eyes when that final moment occurred, but we were glad it was finished.

The Flying Enterprise listing badly before it sank, January 1952

We then headed for our next stop in the still war-torn city of Bremerhaven, Germany. We got there in early January and the city was still leveled from the bombing of six years earlier. It was a very sobering sight, smashed buildings in every direction.

On a good note, at Bremerhaven our ship invited a number of orphaned children on board for a belated Christmas dinner and gifts which made it a special Christmas for all of us. I saw my first snow fall at the age of 21. Unfortunately, one the pictures got cracked, but you can see happy children and Santa Claus in both.

Josephine (Josie) Horrell (nee Langer) was born in 1926 and grew up in Četakovice in then Czechoslovakia. She and her family suffered terribly under Nazi and Communist oppressions. After the war she married Lawrence Michael (Mike) Horrell in West Germany while he was still serving in the American Army of Occupation. For many years she worked in Mattoon, Wisconsin, where she now lives in retirement.

Germans took us over in 1938. What are you going to do? The British turned a blind eye. Roosevelt did nothing. We had it worse with the communists than with Hitler. You couldn’t say anything against Hitler. You had to say “Heil Hitler” when you saw a German. My mother said “Hello” in German. (Laughs) I tell her, “You better say “Heil Hitler” or they take you away.” One guy at a wedding said something against Hitler. 12 o’clock that morning they sent him to a concentration camp. You couldn’t trust anybody. If you listened to American broadcasts you got in trouble. My family did anyway. My brother built a radio so we could listen. I was sent to Arbeitslager, German work camp. They told us we had to help people. I had to work on a farm. The German woman on this farm did nothing. I worked like a dog. I was in this work program two years.

In 1945 I was teaching kindergarten. There was much fighting between Germans and Americans. A plane swooped down so low I saw the pilot; he was a black man. He came back and started shooting. We got the children inside or we’d all been killed.

One time another teacher and I were trying to get home. We got a ride with Germans. American planes came down and started shooting. We jumped in a ditch. I was so scared. Another time we got a ride with Germans. They were deserters and S.S. started shooting at them. We almost got killed then, too. I was so scared, didn’t know whether I was coming or going.

Americans were on a hill near our place. They kept shooting down at Germans. Our house was in the path and got hit. My sister put her feet up to keep the door from falling on the children. Bodies all around -- German, Czech, American bodies! You had to step around them. Czech people stripped the bodies, left them lying there. Terrible stink! Americans made our house headquarters for a while. I had to help carry injured Americans and Germans to the American field hospital. One day an American asked me for a kiss. Kiss sounds something like cushion in German. I brought him a cushion and asked him if this is what he wanted in German. (Laughs)

Did you grow up speaking German and Czech?

I didn’t speak much German till I was in Germany. My mother grew up speaking German. My dad was the main German-speaking person. Before the war he worked for the railroad. There was so much noise one time he didn’t hear the whistle and a train ran over him. I was 8 when he was killed.

After the war many Czechs turned communist. The communists demanded things. They knew my brother had a gun because he was a game warden. They came for his gun. Another day they wanted our bike. Another day they took our radio. Then one day they tell us we had one hour to get out of our house and leave the country. They were supposed to be our friends but they say, “Your money stays in the bank. Your house is ours.” They wouldn’t let us take anything. My mother, her sister, her two-year-old daughter, her eight-month-old son, and I had to leave. We had only the things we could carry. They threw us out of country because we spoke German. Two and half million of us in western Czechoslovakia were forced to leave—all kinds of refugees. I quit talking Czech, didn’t want to have anything to do with those people.

We had to walk to Germany. It was like a death march. We’d stop and ask people for food. One time my mom made me ask people for food. They say, “We don’t have food for people like you.” I ask, “What kind of people you think we are. We’re people just like you.” After that I wouldn’t ask for food. I’d rather go hungry than ask for food. One place they said we could have their leftovers. They finished eating and put their forks in a drawer. Then they all went to the barn. I told my mother I didn’t want to eat off the same forks as those people. She told me to go outside and wash the fork off in water. Some places the people were very good and gave us food. Most time we slept in barns. A farmer let my mother and the two little ones sleep in a bed in his house. They gave my sister and I a blanket each, told us to sleep in the hayloft. It took us over a week to reach Germany. It was very hot. We’d stop early in the day and get up early in the morning so we could walk in the cool. My sandals were falling apart by the time we got to Germany. No one wanted us in Germany either.

How did you survive in West Germany?

My sister knew someone where we could stay. I got a job in a feather factory. German economy was bad after the war. I’d go home with feathers in my hair. You work in that factory and you get feathers all over you. (Laughs)

After the war my mother and sister went back to Czechoslovakia. The Americans were still there. They had to go with an American soldier. They went to our old house to get papers for my brother. He was trying to prove to Germans he had the game warden license. People in our house say, "We don't have his papers. You go to the courthouse." They went to courthouse. They wouldn't let the American soldier in. They say, "Everything you take out of here you spend one year in jail.” My mother and sister went back to Germany, no papers.

Do you recall any happy situations during those hard times?

In Czechoslovakia I had a boyfriend. (Laughs) We went to a movie once a month. There wasn’t much happiness. After the war a bunch of us girls got together and went to dances at the American base.

Where was that?

Furth im Wald. The American guys were having so much fun. One guy cried; he didn’t want to go home. That's where I met Mike, my husband-to-be. He didn’t know how to dance. He danced like an old bear. (Laughs) He was a nice guy and we got married. He sent most of the money home to Kentucky. I had three children. My oldest son was born in Germany. My daughter was born in Kentucky and my youngest boy was born here in Mattoon.

When did you and your family leave Germany?

1950. When we got to Kentucky, the money Mike sent home was gone. His family spent it. He was unemployed for a while. Then he got a job working on a pipeline. I was wondering if I had it better in America. I didn’t like Kentucky. I had an aunt living in Wisconsin. I liked Wisconsin. Mike didn’t want to move there. I told him, “You stay here then. I’m moving to Wisconsin. And I did.” (Laughs) I worked in a restaurant during the day and I worked in a bar at night. I’ve lived here in Mattoon many years. I like small towns like Mattoon.

Did you and your husband live apart?

He finally moved. I told him, “See you can’t live without me!” (Laughs) He said, “The hell you say!” (Laughs) He worked for years in Milwaukee as a welder. He died in 1998.

Now you must have some coffee and pastry.

How delightful!

Special thanks to Margaret Menting for arranging my interview with Josie and for getting the story to her to proof after I returned to Florida.

Mary Sue Koeppel was born in Phlox, Wisconsin, attended high school and college in Milwaukee, and received her MA from Loyola University in Chicago. She is the wife of Robert Gentry, the editor of They Remember War. Her years of service in education spanned 44 years. Teaching is her great love, as is her work as a poet and visual artist. She is the author of two poetry books: In the Library of Silences, Poems of Loss and Between the Bones, Poems. From 1988-2005 she was the Editor of the well-known Kalliope, A Journal of Women’s Literature & Art. Increasingly noted for her paintings, she holds a top award from the Gainesville, Florida Fine Arts Association.

Draft Notice Comes to the Family

One of my earliest memories – the sun is beaming into our dining room and hitting a yellow paper lying in the middle of the table. I can barely see over the table, but know the paper is important. My parents stand off to the side talking in low voices. There is a strange look on both my mother’s and dad’s faces. It was fear. I’d never seen that look on a grown-up’s face. What could be so awful about a piece of paper, I wondered. But I, too, was frightened. Years later, I found out that frightening paper was my Dad’s WW II draft notice.Years later, I saw that same fear on my father’s and uncle's faces as they described the North Koreans who had chased the American troops all the way down to Pusan, South Korea.

Mary Sue Koeppel, flower girl in the ordination of her uncle, Father Benedict Marx, April 1942.

Rationing and Comfort

Another memory of World War II – A young girl, about four, who lived about a mile from my family, died. Before her funeral, her family held the little girl’s wake in their home. I did not know the little girl, but my parents knew her parents and wanted to donate, as folks did in those days, to funeral food for family and guests. To contribute in the most meaningful way possible, my mother used up her meager store of sugar ration coupons to bake a beautiful cake to take to the wake.

My Aunt Marie drove my mother and me to the house where the little girl lay all dressed in while. I remember her white dress, her long, white stockings, and the white ribbon in her dark hair. The little girl was probably just a bit older than I. She looked so peaceful, as if taking a nap in front of all those people.

As we drove home, I remember my mother saying sadly to my aunt, “Everybody brought cakes.” Only years later did I understand her point, that everyone had spent precious ration coupons, hoping to bring a little comfort to the sad event.

WWII German POWs in Wisconsin

I heard a great story from my cousin Jim Koeppel about German POWs held in Wisconsin during WWII. My great Uncle George owned a large farm to which, during threshing season, POWs were sent to help. Most young American men had been drafted, hence the need for the prisoners.

Threshing is very hard, hot labor, so typically huge meals are prepared for the threshers. My Uncle George’s family served the threshers great platters of meats, many kinds of fresh vegetables, potatoes and gravy, fresh homemade breads and jams, and fruit pies, cakes and other desserts. With all this came a keg of beer. POWs and local farmers enjoyed all this together.

When the local sheriff heard that my uncle was serving the POWs such a meal, he rushed out to demand that my uncle stop. The sheriff insisted that by law, POW’s were to be served ONLY baloney sandwiches with water to drink. Nothing else.

My uncle insisted, “No man can do a day’s work threshing on that diet!” But the sheriff was adamant that the POWs get only water and baloney sandwiches.

At noon the next day the sheriff showed up to find the prisoners again eating the nourishing food and drinking the beer provided all the men. “Well, what could I do?” asked Uncle George. “This is my wife’s doing. She brought out the food and beer. Are you going to put her in jail?”

The sheriff threatened my uncle with jail if he did not comply the next day.

Uncle George had to go all the way to his congressman to get permission to serve POW’s good meals while they worked on his farm.

Editor's Note: Mary Sue is the niece of Oscar Koeppel, the next narrator.

Oscar J. Koeppel is a lifelong resident of Phlox, Wisconsin. For many years he ran a successful well-drilling business in the northern Wisconsin area. He is a regular communicant and a lay leader in Phlox's St. Joseph's Church. His wife Audrey died in 1997. From their marriage came 9 children (7 now living), 22 grandchildren, and 32 great grandchildren. During World War II Oscar flew combat missions in Europe as a member of the 773rd Squadron, 463rd Bomb Group, 15th Air Force. Parts of the following story are drawn from a DVD Oscar gave me in June 2012. It is a recording of his interview at the Military Veterans Museum in Oshkosh, Wisconsin. Bolded questions below are mine.

When I first heard about Pearl Harbor I told my girlfriend, "I'm gonna enlist tomorrow." She said, "Why don't you wait till after Christmas?" I said, "No. I'm signing up tomorrow." So I enlisted in the Army and went to Biloxi, Mississippi, for basic training. After that I trained as an airplane mechanic. I didn't like the mechanic job so I tried for aviation cadet school. In Ontario, California, I got 13 hours of solo flying in a trainer plane. In Pecos, Texas, my instructor said, "You're taking too many chances," so he washed me out. I went back to California and a psychiatrist interviewed me. He said I didn't care enough about flying so he washed me out as a bombardier and a navigator. Anybody washed out had the choice of gunnery school or going to the infantry. I said, "I'll take gunnery." (Laughs) So I did a lot of gunnery training and practice shooting. Some guys missed the target and shot at other planes. (Laughs)

Aviation Lesson, ca 1943. Oscar is third from left next to the instructor.

After gunnery school I got a two-week furlough to get married. You didn't know whether you were gonna live or die so you might as well enjoy life. I got married at my mother in law's house in Phlox. We went on a short honeymoon and then my wife joined me in Dalhart, Texas. That's where I met my B-17G crew. Our pilot was Captain Don Jacobs. We called him "Jake." I got the job of upper Turret Gunner and Engineer. We flew over the Azores and landed at our base in Foggia, Italy, August of '44. There didn't seem to be much going on. I said, "Where in the hell's the war?" (Laughs)

Newlyweds Oscar and Audrey Koeppel

Our first bombing mission was over northern Italy. I had 32 missions over Germany and Northern Italy. We had a different plane almost every day because the planes were getting shot up. Many guys were getting killed. We knew we had one chance in ten of getting back to base without being killed, captured, or having to land in a foreign area. We'd get up at 4 a.m. and go out to the plane and wait for the pilot and navigator to be briefed. Guys were waiting and smoking. I said, "Does it help you to smoke?" They said, "Yeah. It calms your nerves." So I started smoking too. (Laughs)

We began a mission with the ground crew loading bombs and ammo in the plane. Then we got in the air, test fired our guns, and circled around for about an hour till all the other planes got in formation. One time I told Jake, "This plane's shaking so bad." He said, "No, it's not. Look at your hands. They're what's shaking bad. I'm scared, too." (Laughs) I thought, They're nothing I can do. So I put it all in the hands of God and I wasn't scared anymore.

Some missions were bad, like Vienna. It seemed like they had a million guns down there. You got two missions credit for a bad mission. Flying over the target was like watching a movie of yourself going through the motions. It's like you're two persons, your body and your spirit, going through the motions. I'd look out the turret and over the wings. It was like a flower garden out there, like dandelions suddenly growing, all that flak and shrapnel flying. They had to repair the wings every day, so you never got to fly the same plane the next day. We were flying group lead most of the time so we tossed out aluminum chaff to screw up German radar.

Did you ever have any contact with black fighter pilots, the Tuskegee airmen?

Oh yeah. Black pilots flew above and below us. They’d break radio silence and we'd hear them chatting with each other. (Laughs) They were good fighter escorts.

One time we ran out of gas. Jacobs said, "You better put your back against the seat. We're gonna crash land." The bombardier said, "There's a fighter base up ahead. We can make it." Sure enough we landed on a fighter base. We landed right in the middle of all these fighters coming in and going out, like a bunch of bees. (Laughs). They took us back in trucks to our base. We each had $48 of escape money and drugs to keep you awake so you could escape. No one asked us for that stuff so we kept it.

I volunteered for a mission that wasn't with my crew. The pilot was crazy. No one wanted to fly with him, but I didn't know that when I volunteered. Oh we had a hard time on that flight. He cussed me out. Our target was Vienna. He said, "This is my last mission. I know I won't make it if I go through with it. We're not flying over there. We're gonna drop our bombs before we get to the target, and if you tell anybody this, I'll kill you." So we dropped the bombs way short of the target and went back home. I didn't volunteer for anymore missions.

One night some mechanics started ragging us. They were all looped up. They didn't like it that we got to go home after so many missions if we lived and they had to stay. They said, "We're gonna be washing your blood and guts out of your plane before you go home." They were just being nasty and jealous. I had many close calls with disaster. Only my complete trust in God kept me from getting hysterical like some did.

Did you ever have any misgivings about bombing the country where your family came from?

None whatsoever. Hitler and his crowd started the war. It was our job to finish it. My last mission was December 9, 1944. The target was Regensburg, Germany. We lost two engines but the plane could still fly. Jake asked for a vote on where to land, Russia or Switzerland. Naturally we all chose Switzerland. I shot off 24 flares, enough to stop traffic on the ground to look at us coming in. No planes came after us. No one shot at us. Jacobs made a wonderful soft mud landing near Altenrhein. No one was hurt. Armed guards marched us to a tavern where we were given beer and pea soup. It was the best food we'd had in months. I fell asleep after two beers. (Laughs) We played cards and relaxed before a bus took us to Adelboden. The officer in charge of the town gave us forms to send home through the Red Cross letting them know we were safe in Switzerland. I was in Adelboden about a month. I stayed in two hotels, part of the time under armed guard. The rest of the time we were pretty free to go and come in the town. I attended Christmas Eve mass in a beautiful gingerbread-decorated church. New Year's Eve we had a great party with plenty of beer. Ice skating kept us busy for about a week. We got pretty good treatment from the Swiss. They were short of food. They took in thousands of refugees and had to depend on Germany for coal and food.

Don Jacobs; Ralph Mathewson, the radio man; and I decided to escape. We knew if we were caught we 'd have a really bad time in prison. Other guys stayed put. They were having too much fun. (Laughs) I escaped because I wanted to go home and see my wife. I feel I deserve POW status. I was held in Switzerland against my will, and I took a great risk getting out of there. We used forged passes and hid from Swiss soldiers hunting for us. We got help from American authorities and the French underground. We got in a boat to go across Lake Lucerne. The engine wouldn't start so another boat had to pull us across. It was January 1945. I got so cold my legs wouldn't work. When we got to the other side, I had to crawl out of the boat on my hands and knees. We got into a truck and went over the mountains into France. We almost got killed on a mountain road. The truck spun around, almost turned over.

Technical Sergeant Oscar Koeppel, ca. 1945

When I got back to the states I had two weeks of R and R. My wife and I had a good time in Miami Beach. Then I went to Laredo, Texas. They wanted me to be a gunnery teacher, but I told them I was too stressed out to teach. So they sent me to a doctor. He asked, "Are you really stressed out?" I said, "No, but I really don't want to teach." The doctor said, "Okay. I'll take care of that." Then I spent a month as crew chief at Randolph Field. Then they sent me to a different field where I was discharged. I hopped a bus and went home.

I'm 93 now. I like to meditate on God and pray and sometimes I'll fall asleep. Then I wake up and what the hell, I'm still here. (Laughs)

Fredric (Fred) Kratina is a retired physician and a founding member of Oak Hammock at the University of Florida. He retired from the U. S. Air Force Reserves in 1973 as a Lieutenant Colonel. While in the Air Force he practiced Aeromedicine and served as a liaison officer with the Civil Air Patrol. After resigning from the Regular Air Force, he became a Diplomate of the American Board of Obstetrics/Gynecology. While in the Air Force Reserve he obtained Board certification in Psychiatry/Neurology and founded the Family Study Center, a free-standing psychiatric day hospital in Delray Beach, FL. After retiring from the Air Force Reserve, he headed the Women’s Clinic at the University of Florida and was a psychiatrist at the Bradley Center in Columbus, Georgia. Sandra, Fred’s wife of 43 years, held Bachelor and Master Degrees in Nursing and a PhD in Education. She headed the LaGrange College School of Nursing for 17 years. She died of cancer in 1999. Sandra and Fred had four children, five grandchildren and one great granddaughter. Karin, the oldest daughter, practices nutrition therapy in Gainesville, FL

On February 5, 2010, in Oak Hammock’s Meditation Room, Fred told me about some of his experiences, starting with his life in Germany before World War II.

I was born in Dresden, Germany, in 1926. For 20 years my father Rudolf was a cellist in the Dresden Staatskapelle and Oper [Dresden State Orchestra and Opera]. My grandfather, a violinist, and great grandfather, a violist, each performed for 40 years in the same orchestra. My father also sang professionally in Berlin. He made his debut as Sarastro in Die Zauberflote [The Magic Flute]. My aunt Valeria headed the Dance Department at the Staatsoper and also taught dance. She excelled as a dancer at Hellerau, the famous center for modern dance. A Dresden street is named after her: Kratina Strasse.

My father and uncle served in the military during World War I. My father Rudolf was kicked out of the cavalry by a horse. In the groin! (Chuckles.) He joined the German equivalent of the USO and received six medals for his service, which he proudly wore on occasion. My uncle Friedrich flew as a fighter pilot and an observer pilot. Toward the end of the war he was missing in action.

Your surname is Czech, isn’t it?

Yes. My grandfather Josef was born in Volovice near Prague. My mother's maiden name was Marguerite Pressly of Augusta, Georgia. Her father Charles was a foreign-service officer in Paris for many years including service during World War I. Immediately after cessation of hostilities, Marguerite went to Berlin to look for some old friends. Rudolf was then trying to find out about his brother’s disappearance, plane and all. That’s when my parents met. Soon he had Marguerite looking for Friedrich through diplomatic connections. Friedrich’s body and plane were never found. An early MIA! After Marguerite and her father returned to Augusta, she and Rudolf corresponded for five years. The Pressly family didn’t like the idea of Marguerite marrying a German musician. However, they did eventually marry in Baltimore. That's where his boat landed. (Chuckles.) They went back and settled in Germany. We had a nice apartment in Dresden. I had good schooling, loving parents and grandparents. I fondly recall the trips my father and I took to Jonsdorf in Bohemia on the Czech/German border. Jonsdorf was my grandmother’s ancestral home. My father’s reputation as a musician earned him honorary citizenship of that village.

The Kratina family in their parlor in Dresden, ca. 1934

But a cloud hangs over my childhood. One of my early memories was about 1934 coming home from school and passing by the Waldersee Platz, a park in our area. Loudspeakers were blaring from the trees. Later, a kiosk in the park showed pictures of ugly-looking people under glass. They had penetrating eyes, hooked noses, wiry hair. I asked my parents about all this. They said, “Shhh! Never talk about this outside.” They told me the people in the pictures were Juden. Nazi agitators were promoting anti-Semitic demonstrations. My parents didn’t approve of them. I was instructed not to talk about it, not to talk to anybody about it. I was told over and over again to keep my mouth shut about this kind of thing. There was a prevailing fear that somebody would come and get you, take you to the KZ [German abbr. for concentration camp].

By this time my father had shaken hands with Hitler. This happened after an opera performance. Hitler wanted to thank orchestra members for the music. They lined up and Hitler shook hands with each one. On another occasion, my mother and a friend were standing near the door of the Bellevue Hotel in Dresden. Hitler was coming out. My mother and her friend wanted to get a good look at him. My mother had always thought his moustache and hair combed down one side looked ridiculous. When he came out, Hitler looked directly at my mother. She was struck by his charismatic expression. He had very piercing blue eyes.

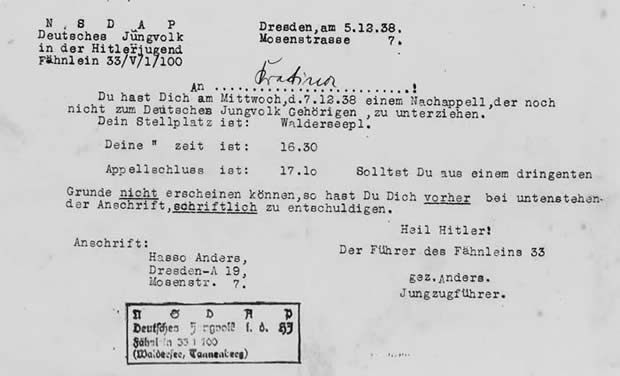

Were you in Hitler Youth?

I wanted to, but my mother wouldn’t let me join. My friends were in it. They spent weekends in the mountains. They played games, camped out, did rough sports, and other exciting things. I felt bad I couldn’t join the fun, but Mother absolutely forbade it and my father suggested that I might join sometime later on. Eventually an official document ordering me to appear in the park where the Jungvolk [Hitler Youth] met arrived at the house. I had been expected to join the group as a normal German youngster but since I had failed to do that, I was ordered to appear. My mother responded that I had suffered from diphtheria and was in the country recuperating and that I would certainly report when I returned. She didn’t mention what country I was recuperating in; actually I was in the United States. My parents had brought me to Charlotte, North Carolina, at the tail end of 1937 ostensively on vacation but had enrolled me in St. Leo’s boarding school attached to Belmont Abbey and left me there. My mother’s uncle, George Pressly, had practiced surgery there as did his daughter Maude, also a physician. She would come and visit me periodically and very lovingly try to make things better during that year my parents left me there. St. Leo’s had been picked because of her and because there were a few Catholic nuns at the school originally from Germany who could speak my language while I learned the new one and also more about my faith.

Original document from the Leader of Little Flag Unit 33, Hitler Youth. It orders Fred Kratina to a hearing on July 12, 1938, in the Waldersee Platz beginning at 4:30 p. m. and ending at 5:10 p.m. In the first sentence, the familiar form of the word you in German [Du, Dich] means that the order applies to the child Kratina. The last sentence says, “If you should not be able to appear because of an important reason, then you must excuse yourself beforehand in writing to the address given below.”

But Maud couldn’t change the situation I was in at St. Leo’s. I was eleven years old, away from home for the first time. I was a scrawny kid who didn’t know English and missed my parents terribly. The bullies had a field day with me. I was frightened and couldn’t fight back. I felt overwhelmed trying to adjust to a different life, quite alone. I remember that awful year as the worst in my 83.

By the time the war started in 1939, my parents and I had settled in Augusta. My mother was no longer as socially acceptable as she had been because her husband was German. Fortunately, he got a part-time job at the University of Georgia teaching music three days a week. In 1940 we moved to Atlanta and I enrolled in Marist College High School. When the U. S. got in the war, we had to register as enemy aliens. Elsa Michel, our long-time maid, was able to get to the U. S. through Norway. She was a fine worker and wonderful friend to the family. She was like my alternative mother. She continued in our family until her death around 1966.

When you were living in Dresden, did your mother have any trouble with the Nazis because of her American background?

About 1936 she was “invited” to Gestapo Headquarters to be interviewed. She didn’t know why. She had to be there at 4 a.m. sharp. There was little transportation in Dresden at that hour, so she rode her bike. The Gestapo was fishing for information: What do you know about this? What do you know about that? What do you know about so-and-so? They asked her about our next door neighbor, Baroness von Nettelbach who was of English extraction. Mother gave them little information; they allowed her to come home. By then the unrest in our home was so thick you could cut it with a knife. This Gestapo thing was the final factor in my mother’s decision to leave Germany. My father was not as eager to leave, but he thought it best he did.

One of my father’s orchestra friends was a Jew. He was anxious to leave Germany but didn’t want to leave behind his gold. He asked my father to help him make a foundry in the man’s basement. They set up the foundry and converted the gold to barbells. The man was able to smuggle the gold out that way.

When did you become aware of the Holocaust?

Growing up in Germany, I became aware of the Nazi persecution of Catholics, Jews, and other religious groups. These were the reasons we left Germany. My mother said, “I didn’t raise you to be cannon fodder or an atheist.” The Holocaust was sketchy to me until long after I’d been in the states. Living in the U. S. during the war, I had mixed feelings. I was anti-Nazi and pro-German. After all, Germany was the country that gave me my birth. I was also aware that if I’d stayed in Germany, I would be dead. When I heard about the Allied destruction of Dresden, I felt I’d been attacked and was sad.

After the war, I graduated from high school and enrolled in Holy Cross College. By then I’d acquired a Southern accent and people at Holy Cross teased me about my accent. All my life I’ve been quick at picking up accents. In Germany when I was on vacation, I adopted the speech patterns of the kids I played with. When I came in for lunch, my father could tell what areas of Germany the kids I’d played with were from. When I came home from Holy Cross, my Atlanta friends said, “You talk like a damn Yankee.” (Laughs.)

At Holy Cross I met Hubertus von Lowenstein. He had been in charge of a Catholic Youth group in Germany. He was virulent anti-Nazi and got in trouble with Hitler. Hubertus took me under his wing. He felt the same way I did about Germany and the Nazis. He filled me in on a lot of happenings in Germany during the war. He was a friend of Dorothy Day [Catholic social activist] and had applied for U. S. citizenship. When the Allies bombed German cities and killed thousands of civilians, he gave up his application. He said the Americans and British had become as bad as the Nazis. Eventually he returned to Germany right after the war and took part in an effort to save Helgoland. This area of two islands had been a German naval base during the war. Hubertus and others would go to one of the islands, about 35 miles out in the sea, and wave flags. This way they kept the British from destroying it.

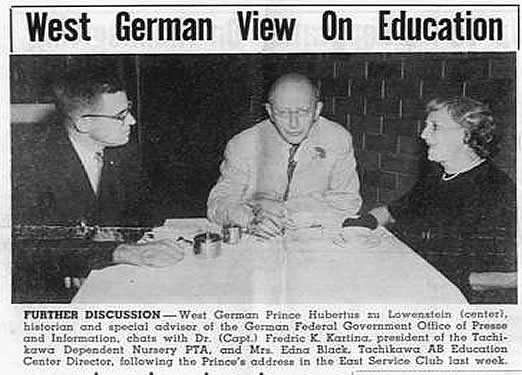

Photo taken at Tachikawa U. S. Air Base in Japan, published December 1, 1961. Prince von Lowenstein (center) spoke on “Crisis in Education: East and West.” Dr. (Capt.) Fredric Kratina’s last name is misspelled.

What did you hear about the Soviet invasion of eastern Germany?

Just about everywhere the Soviets went, they raped and pillaged. There was going to be a continuation of the misery index in Germany. My aunt Valeria told how frightened she had been when the Russians occupied Dresden. Her house was one of the few not destroyed by Allied bombs. When the Staatsoper was bombed to smithereens, she was out of a job. One day a jeep came by with a Russian officer and his driver in full battle dress. The officer got out and knocked on my aunt’s door. He was courteous but spoke poor German. He pointed to Valeria’s piano and asked if she would play for him. She allowed him in and played classical pieces for him. After two hours, she was running out of music to play. He thanked her and asked if he could come back and listen some more. She of course said “Yes.” Only thing she could do in that situation! The officer left his driver at the front door to keep other Russians from breaking into the house. He came back during the week just to listen to her play. He was a music lover and apparently more civilized than many Soviet soldiers.

My aunt survived the war, married and moved to Oberhausen in West Germany. Her husband became Head of Music in Oberhausen. After the war, there was a remarkable effort toward peace in Dresden that went on for years: the Frauenkirche [Church of Our Lady] was finally put together. This was accomplished through rebuilding efforts in Germany and financial contributions from countries that had been on the Allied side during the war.

I assume your enemy alien status was removed after the war and you became a citizen.

Yes. I graduated from Holy Cross in 1947 and from the University of Georgia Medical School in 1952. I became a U. S. citizen while I was still interning at Jackson Memorial Hospital in Miami. I joined the Florida National Guard and was activated in 1952. At Camp Chaffee I was in charge of bedwetters. My job was to help them or get them out of the Army. I’d talk to them and say, “Why don’t you try emptying your bladder before you go to bed?” I separated more men from the Army than I retained. My job was mostly paper work and I hated it. I wondered how the hell I was going get out of the Army, even thought about pissing in my bed. (Laughs.) I got out by joining the regular Air Force. By that time I’d fallen in love with a lovely nurse I’d met in Miami. When I was assigned to San Francisco, Sandy came out and we got married. Most of my active military career was in OBGYN.

How did you learn about the Nazi execution of your granduncle?

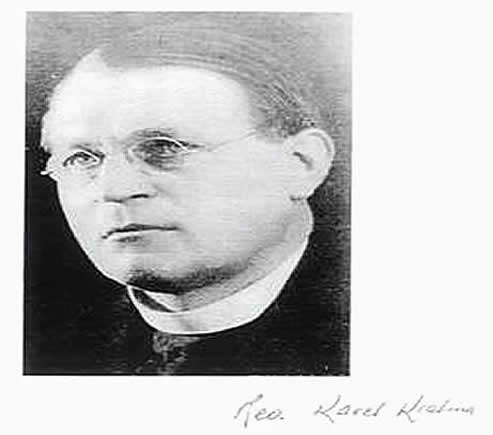

I have several of his letters written to his sister-in-law, my grandmother Frieda. I didn’t hear about his execution till I was in Augusta after the war. My parents never talked about it. My granduncle was executed in Pancraz, the Prague jail the Nazis had taken over. They used their own guillotine equipment. According to Radomir Mlady in his book Catholics in the Shadow of the Swastika, “At the beginning of the year 1945, Karel Kratina, a 62-year-old pensioned high school professor of religion, was beheaded because he allegedly said in front of a Nazi informer [a church sacristan] as they were walking by the villa of the State Secretary of the Protectorate K. H. Frank: ‘Here is where that rascal Frank lives.’ Before the court, however, Father Kratina denied this. He did, however, admit to the accusation that in a sermon at a May church service he warned against false gods, actually mere humans, to whom monuments are built while they are still living.”

Here is a translation of the letter Father Kratina wrote to his family shortly before he was killed. His body was never recovered.

Beloved,

I had a sad Christmas Eve, even sadder New Year’s Day 1945, but the saddest day was my birthday, when it was announced to me in the afternoon that I did not receive clemency and that I will be on Friday the 16th of February, that is today, beheaded. By the time you read these lines, I will no longer be among the living. Today, exactly 64 years ago in 1881, they carried me just a tiny infant from Volovice to Zemechy to holy baptism. And today?

God, I admit my sinfulness, but I certainly do not deserve so much. I am not a thief, but an unfortunate person. But I forgive my enemy according to the will of Christ. Just deliver the message to him [sacristan], that I will remind him in the last moments of my life the retribution of the just God and I will call him within a year and a day to the Judgment Day.