|

George Lewis was born and raised in Indian Rocks Beach, Florida. His educational experiences include studies at the Universities of Florida, Tampa, and Loyola. For a number of years he served as a Public Health Advisor for the United States Public Health Service. He now resides at Oak Hammock at the University of Florida and maintains keen interests in health issues, international travel, politics, sports, and the internet. He is a key contributor to Oak Hammock's highly successful Recycled Riches Program.

* Why and when did you join the Coast Guard?

I joined to avoid the draft; and I grew up around the water on the Gulf. I joined in March 1959 and spent six months on active duty at the Coast Guard Training Center in Cape May, NJ. After my three months of basic I stayed on as part of the permanent party at the base. I worked in the recruit classrooms, played in the base band and stood duty in the recruit barracks every 4th night. Here's a picture of me taken after I'd completed boot camp.

Seaman Apprentice George Lewis

* What unit were you in? Where? What was its mission?

After completing my six months of active duty I was in a Port Security unit in St. Pete. I became a Petty Officer 2nd class with a Port Security rate. I served active duty for training (two-week summer tours) at NAS Jacksonville, Coast Guard Air Station, St. Petersburg and at the Coast Guard Base, Yorktown, VA. Between my junior and senior years in college, I was on active duty at the Coast Guard Base, Yorktown, VA. In the summer time, this base trained enlisted reservists. The rest of the year it was used to train officer candidates for the Coast Guard. At that time I did general support work for the instructors and was also an instructor in fire fighting.

Most of the reserves were not exposed to fire-fighting in their training, that is until they got to Yorktown in the summer. My job was to take the trainees into a large oil fire. The fire pit was an area about 40 feet square and about 5 inches deep. After a couple of fires this area was filled with water. Five to ten gallons of diesel oil was poured on top of the water and set on fire. It made a blaze that covered the area and went upwards of 30 feet or so into the air. There were two hoses manned by the trainees. They were dressed in heavy fire retardant coats that went to their knees, as well as gloves and boots. This was summer time in coastal Virginia and it was hot, just standing around and extremely hot facing into the fire.

The trainees were divided into two groups (for the two hoses). They had been told how to approach the fire and how to handle the hoses, using a fine spray which they rotated. I stood between the two groups and walked into the fire pit with them, shouting encouragement and directions. The fire lasted about 5 minutes, but to most trainees I'm sure it felt like it was much longer. No one was injured while I was taking groups of trainees into the fire.

The men came away with a feeling of confidence should they ever be called on to fight an oil fire either aboard ship or in a port environment. In addition I also conducted a class in the proper use and charging of hand held devices for putting out small fires.

* Did the mission perceive any direct or indirect threats to the U.S.?

Oh a lot of the older guys were sure we'd be invaded at some point. The general thrust was to focus on potential attacks on American ports and understanding what was being shipped into the ports. During the Cuban Missile Crisis I was asked if I wanted to volunteer for active duty. I declined because I'd just returned to college. No one was called up from the unit at that time.

* What was the composition of your unit, the ratio of enlistees like yourself to career Coast Guard?

The majority were enlisted guys, some with prior service, senior enlisted guys; officers had been on active duty as well, but all were reservists with some expecting to stay in the reserves long enough to get retirement. In retrospect, I should have stayed in another 14 years for the retirement.

* Did you note any attitudinal differences between said enlistees and the career types? If so, what were the most striking differences?

In boot camp the guys that had signed up for 4 years envied those of us who were going to be there for 6 months. Most all of the guys in my boot camp company had several years of college; there were no high school dropouts. One guy observed if he had known he was going to have to study so much he would have gone into the Army.

* What special challenges did you have to deal with in carrying out your part of the mission? Which challenge stands out the most?

There wasn't anything that stood out as a challenge. It was to use a phrase, a piece of cake.

* What is the funniest situation that you recall?

Watching the response by reserve officers deal with a career office over a thermostat in a steel building in the middle of a Virginia summer. Temps in Tidewater Virginia can be high along with the humidity in the summer. The regular Coast Guard officer insisted that the building be at 80 degrees. The reserve officers, mostly high school teachers or college professors, thought it should be closer to 74. It was a constant battle, the regular officer would come in and raise the temp. He'd leave and the reserve officers would turn it down. This went on for several weeks. Finally, the reserve officers had enough of this behavior. They turned the temp down as low as it would go and broke the control off the thermostat so the temperature could not be turned up.

A current resident of Oak Hammock, who was there during one or more summers, told me that the regular officer was kicked out of the Coast Guard. I had heard stories about him before I got here too. One was he couldn't find a weapon that was missing from the armory. I'm more inclined to think it was something more personal.

John M. Lloyd and his late wife Patricia are founding members of Oak Hammock at the University of Florida. Their marriage produced three children, and from these came five grandchildren. For many years John was a successful executive in laundry service and in the uniform supply and rental business. Patricia was a homemaker and served a long time as a volunteer worker. John's Navy service in World War II included over a year at sea with a gun crew and almost another year of duties at Camp Shoemaker in California.

I was 17 when I entered the Navy July 5, 1944. After boot camp, I was sent to Hugh Manley High School in Chicago. Part of the school then was being used by the Navy for radio training. My grades were poor, so the Navy sent me back to Great Lakes Naval Training Center to be interviewed for a job. I volunteered for armed guard on a merchant marine ship and they sent me to Gunnery School in Gulfport, Mississippi. I trained on a 5" 38 caliber gun. All the training guns were wooden. At Shell Beach, Mississippi, we trained with live ammunition.

After gunnery training, I was assigned to the SS Fort Laramie in Panama. The ship had 25 Navy men and about 25 to 30 merchant seaman. Our ranking officer was a lieutenant junior grade. The rest of us were enlisted men. I soon attained the rank Seaman 1st Class, equivalent to a corporal in the Army. Our ship carried different grades of oil and different grades of fuel. I was part of a 7-man crew that handled the 5" 38 gun on the ship's stern. There were four 20 mm guns on the first deck and one 3" 50 caliber gun in the bow. The ship was also equipped with depth charges, located near the stern.

Do you recall the name of the lieutenant j.g.?

I'm sorry I cannot. The names of most of the guys I served with escape me now. I do remember one, Paul Lies. I think he was a trainer in our gun crew.

We left Panama about January 18, 1945. Our first stop was Hollandia, New Guinea, but we weren't allowed to go ashore. The Navy had a huge supply depot at Hollandia. The place became like a home port for us. Our next assignment was Leyte Island in the Philippines. We were part of a convoy of about 50 ships. Our position was in the middle of the convoy where I thought there wasn't a great chance of being hit by a torpedo. Little did I know. The second night out a ship about 300 yards from us was hit by a very large explosion. We thought it was done by a Jap submarine. None of the ships carrying supplies stopped to help the badly damaged tanker. I'd been ignorant of the danger we were in. Now I finally realized the danger of being easily seen by the submarine with all the burning fuel around us. Eventually U. S. Navy ships guarding the convoy tried to help the struggling merchant marine crew. Later I was told no one had survived. For the first time it struck me that we were in a real war.

We finally arrived at Leyte, my first visit to a country at war. There was a great deal of fighting on the shore and in the wooded areas about one or two miles from us. I saw Jap planes bombing and strafing American positions.

Did you come under fire at Leyte?

No. Nothing was fired at our ships in the harbor. I wasn't afraid of being hit by Jap planes. They were concentrating on land warfare. After a while I figured if they were gonna bomb us they'd have done it by now. We sent oil ashore via oil hoses. We had many hoses and we could lay a lot of oil in a place. On ship I couldn't see the tanks we were filling. Two days later we left Leyte for a return trip to Hollandia. From Hollandia we headed for Bahrain in the Persian Gulf. The temperature was a high 126 degrees, the Gulf water a very light blue. We stayed in Bahrain about two days and headed for Darwin, Australia. We took on food supplies for a trip to the Admiralty Islands. Few ships were there. We dropped off supplies and left the following day.

We came on some loose American mines. We fired every weapon we had at them but without success. We couldn't get too close for fear of hitting a mine so we swung around the mines and went on. We got orders to return to Hollandia. On the way back we stopped at Peleliu Island where there'd been a terrible battle with the Japs. I'm surprised the paper didn't give the battle more news--they were due it. We dropped supplies at Peleliu and headed back to Hollandia. The war appeared to be slowly ending.

Did you ever fire at any enemy?

Only once outside Leyte. We saw Japanese planes and fired at them but they were too far for us to hit any.

Did the Laramie drop any depth charges?

Not on any subs. Merchant mariners manned the depth charges, but they were seldom used and then just for practice. The only Jap sub I knew of was the one that I told you about, that torpedoed a ship in our convoy to Leyte.

What was your job in the gun crew?

I had several jobs but wasn't very good at any of them. I can't recall them exactly now. I believe one time I was a pointer, another time a trainer. I never could understand sight setting. They wanted me to be a signalman. I was totally inept at that. (Laughs)

You'd think merchant mariners could keep their refrigeration equipment working, (Chuckles). The refrigeration went out so we headed to Pearl Harbor to get it fixed. During the trip to Pearl all the Navy got to eat was K-rations.

In all our time on the Ft. Laramie we Navy guys weren't allowed to leave the ship. After the war, the captain of our gun crew did get off and went into town. I think he got off somewhere around Panama, but I'm not sure of that. He was not a likable guy. He apparently fooled around on shore because later it was common knowledge he got gonorrhea and syphilis. Our bursar handled finances, but he also did other things, like giving shots. One time I saw him take a big syringe and give our gun captain a shot.

There was poor interaction between us Navy and the civilian crew, a lot of whisky drinking among the merchant seamen. The Navy had beer but the merchant guys wouldn't give us access to the whisky or let us in the engine room. I saw the captain only once. According to some civilian seamen, the captain stayed in his cabin and boozed it up. The merchant first mate ran the ship. Eventually the captain was relieved. We got another captain, but he didn't last long. Then we got a third captain. I don't remember much about him. He may have been better than the other two but that's not saying much.

Every night merchant mariners blew out the smokestack and blackened the deck and the guns. We Navy guys had to constantly chip away blackened paint and lay down cobalt blue paint. If you didn't have anything to do, you got a paint job, either chipping or slapping on paint. I spent many an entire day chipping paint.

In wartime there's always a great need for warm bodies, so the civilian and military services don't always get the best caliber of men. The civilian crew on the Fort Laramie was a boisterous lot. They constantly moaned and groaned that they weren't getting enough money. They bitched about having to do Navy drills and pass ammunition to us. I saw many fights, merchant seamen slugging it out with other merchant guys and Navy guys pounding on each other. I found the best way to get along was to keep to myself, not argue, not say much.

The civilian bosun on the ship was pretty old. I think he'd been in World War I. Suddenly he disappeared. Several merchant guys said he'd been thrown overboard. I was amazed. He was smart and knew how to fix things. He seemed like a nice guy. I didn't think he was unpopular. There was no investigation, nothing else about him. I got to feeling I was on a ship from hell.

One time at Pearl Harbor I had the afternoon watch. My only company was the 5" 38 caliber gun. After a while I noticed a ship slowly making its way to the harbor. Before long I saw the ship listing to one side. The entire ship looked to be badly damaged. Little did I know. The ship continued on and I could see it would likely take the dock space in front of ours. It did exactly that. This carrier was the USS Franklin and the crew looked exhausted and dejected. They stood at parade rest and were making the best of it. They had a band playing the Navy hymn, "Eternal Father." It was an extremely sad moment. I'll never forget that day.

Before long we heard what happened to the Franklin. It had left the convoy to get close to the Japanese mainland to launch fighter planes and attack key targets. A Jap plane came in low level and bombed the ship. The carrier's elevator and a good part of the flight deck were destroyed. The Franklin was a mass of flame and fire. The heat was intense in almost all parts of the ship. It was very hard to put out the fire. Many enlisted men manned the hoses and turned them on full blast. A chaplain organized and directed rescue teams.

An enlisted man asked to help a burned sailor. The chaplain gave the go-ahead. When the sailor reached the badly burned man, the sailor extended his hand in friendship. The burned man could not hold the hand of the brave sailor. The sailor then reached with his hand and started to shake hands with the burned man. Suddenly the hand and arm came loose from the burned man's body. He had been dead for many hours.

Years later I read a good book about the Franklin. It told about the ship being hit by a 250-kilogram bomb. The bomb set off a chain reaction of exploding ammunition and aircraft fuel. Lieutenant Commander Joseph O'Callahan, a Catholic priest, was the ship's chaplain. He gave last rites to many wounded and dying men, and he directed the rescue efforts. He was the first American chaplain ever to be awarded the Medal of Honor.

This photo was taken from Wikipedia.

According to the book on the Franklin, the injured man was Bob Blanchard, and he survived.

The worst area on the Franklin was the hangar deck just below the flight deck. Three hundred sailors were trapped down there and there appeared no way to rescue them. Finally, Lieutenant (j.g.) Donald Gary found an entry place, and he was able to go in there and lead groups to safety. He also got the Medal of Honor.

Through the heroic efforts of many brave men and the light cruiser USS Santa Fe, which picked up a lot of wounded, many men were saved. But the casualties were terrible: 798 dead and more than 487 wounded. The Franklin was able to get enough power to hobble back to Brooklyn Navy Yard. It was rebuilt and reactivated, but unfortunately in 1966 the ship was scrapped.*

Our ship continued in the Pacific and gave other ships and ports supplies. Finally the big day came when the war was over. I think it was off Hollandia when we cut loose with our guns and fired the V for victory sign in the air. There was so much gun smoke we couldn't see any V (Laughs) Soon we were throwing all ammo into the sea. Who decided on this strange activity I don't know.

How did you feel about that?

I didn't like it. It was a terrible waste. The projectiles, canisters and all that stuff had to lifted on pulleys and brought to the side of the ship and thrown over. It was a big job, took a long time. We kept the guns.

We finally returned to our stateside base, New Orleans. These were happy days. We got paid and a 30 day leave. I had a great vacation at home before being assigned to Shoemaker, California, for processing. It was a huge base, and the mess halls could hold up to 1,000 men in one or two sittings. Shoemaker was where many of us went when we didn't have enough points to get discharged. We bunked in Quonset huts. It was the old military thing of "hurry up and wait." You quickly learned that you might be called in two or three days or a number of weeks to be interviewed. There were five interview desks and the lines were very long. The interviewer always asked everybody the same question, "Ship or island?"

Finally my time came to see the interviewer, an old Navy Petty Officer. When he asked "ship or island" I said, "Neither." I thought this remark would cause some bodily problems. Fortunately it did not. He seemed to gather his senses and asked, "Well what do you want?" I told him I could type. He handled it well and said there was an opening at the Marine Brig. When I reached the brig I wasn't quite sure I'd made a good choice. No time to think things through. I went in and a young guy said, "May I help you?" I told him of my "skill." He said the job had been filled in the past 20 minutes. My heart sank.

I got back in that long, long line. Fortunately, I got the same interviewer. He told me there was an opening at Group B Headquarters. I became a clerk typist at Group B, even though I could type only 15 words a minute. Duty was good there. My sleeping area was much better than bunking in a Quonset hut.

One time I had the night watch. A big, tough-looking guy came in, face flushed, very drunk. He'd been assigned to scullery duty, and I tried to remind him of that.

Drunk: By God, I been in this man's Navy six years and nobody's gonna make me do damn pots and pans.

Lloyd: Just a minute, please.

I went to the Chief Warrant Officer's (CWO's) room. I woke him up and told him the situation. He was a tough cookie, imposing, like a bearcat. I don't recall his name exactly, something like "Workingteen." Anyway, we both walked out to meet the drunk. The guy kept raving about being in the Navy six years and be damned if he was gonna do any scullery work.

CWO: Are you through?

Drunk: (cursing, babbling)

CWO: I've been in this man's Navy 33 years and I'm telling you, you are going to pull your detail. Lloyd, call the Shore Patrol. Tell 'em to bring SP's down here and escort this man to the scullery.

Lloyd: Yes sir.

Soon three SP's came in. One took hold the drunk's one arm, another grabbed his other arm, a third handled his back and they marched the guy right down to the scullery. (Laughs)

I got to know a lieutenant who'd also served in armed guard on a merchant ship. He was a very nice guy and loved to play ping pong. He asked me if I could play and I said I could. He said, "I like to play every afternoon at three except weekends. Let's clear out the supply room and set up a table." So we did. I forget where we put the supplies, but we had plenty of room to play ping pong. (Chuckles) We played a lot of games and I beat him every time. (Laughs) When it got close to my discharge time, he wanted me to stay at Shoemaker and play ping pong. I guess he was hoping he'd eventually beat me.

After about eleven months at Shoemaker, I was sent back to Great Lakes and discharged on June 5, 1946. It felt great to be a civilian again.

The Franklin and World War II were very much on my mind when I recently attended Pearl Harbor Survivors and World War II Veterans Recognition Day. Here's a news clipping from the Gainesville Sun. That's me in the blue jacket, far right.

* Joseph A. Springer. Inferno: The Epic Life and Death Struggle of the USS Franklin in World War II. Zenith Press, 2007.

Jack W. Martin was born on Flag Day 1928 in Ft. Lauderdale, FL. His father was recognized by Governor Lawton Chiles for outstanding work in civic activities from local to international levels. In 1958 his mother became the first Ft. Lauderdale Clubwoman of the Year. In 1987 she was honored as Grand Dame for the International Swimming Hall of Fame. While serving with the Army in Dexheim, Germany, Jack met Evelyn Rolfs, one of two American teachers hired to teach dependent children of military families. They married in Mainz, Germany, and now have five sons, three grandchildren, three step-grandchildren and five step-great-grandchildren. Jack grew up during World War II and recalls important happenings of that time. A West Point graduate, he spent 24 years in an Army career that included many challenging assignments.

I recall the ration books and war bonds we used during World War II. My father’s contribution was to walk to work every day to save gas. He also did pro bono work as a lawyer and had to barter his fees to keep the family of three children going during the Great Depression. We also had a Victory Garden in our front yard. As the oldest child, I usually weeded and mowed the yard. Then I got the job of weeding and tending the garden.

There was a small Coast Guard station in Lauderdale, and the Navy took over several beach hotels. We watched as gunnery practice took place from towers on the beach at small-plane drag chutes. We had “brown outs” at the beach because German submarines patrolled the coast. They torpedoed a number of our ships. We could see smoke from damaged ships floating up the Gulf Stream. Also, yard signs at beach hotels said “Gentiles Only” and blacks were not allowed on the beach except with a white family. Lila was my baby sitter.

My mother was a school teacher and the absence of male teachers away to war was a concern, so I went to Culver Military Academy, a prep school in Indiana. This was fortuitous as it became a ticket to West Point following one year at the University of Florida. I mention this year because it was cheaper to have laundry mailed home than to pay for it locally.

I graduated from West Point in 1951 as a Second Lieutenant in the Corps of Engineers. My guiding principles were: always to remember the motto “Duty, Honor, Country,” do what is right even if it’s harder, be truthful, set an example, listen to your senior sergeants, and take care of your men. Also, remember that your education was paid for by the taxpayers.

Army careers normally encompass a combination of school, staff and command assignments. In my case it started with Engineer basic officers training at Fort Belvoir, VA. Then in 1953 I was assigned to the 17th Armored Engineer Battalion in Dexheim, Germany. The battalion mission was to assist the mobility of armored units of the Second Armored Division. Their mission was to help delay or defeat any Soviet invasions through the Fulda Gap.

At Dexheim, our major annual training event was installing a floating bridge across the Rhine River. It was exhilarating to see that first tank cross safely. As part of the S-3 Operations office, I had to check plans for placing explosives in certain river craft if it became necessary to sink and block selected estuaries in the event of Soviet advances. The challenge for us young officers in this battalion was to meet the preparedness expectations of the senior officers and enlisted men. They were hardened World War II veterans.

M47 tanks crossing the Rhine on the bridge just completed by the 17th Army Engineer Battalion

One of the first lessons officers learn is that you are responsible for all phases of life for those under you, including health and welfare. In postwar Germany, many soldiers were looking for fun. VD control was one statistic each unit tracked. This meant those infamous and surprise “short-arm inspections” before Reveille. Suspected rape occurred in one of my companies. “Bailing out” soldiers for drunkenness in town was all too common. It was disconcerting that the best equipment operators and mechanics essential to the mission were typically the ones caught.

My time in Europe then was memorable for the military training I received and especially for my 1955 marriage to Evelyn. The wedding ceremony was conducted by the Mayor of Wiesbaden. It was in German, and we were cued to say “Yes” at appropriate times. The only available Best Man was a fellow female teacher who needed a ride to town. The wedding only cost 50 Marks ($12.50).

Europe has an excellent rail system. Before we were married, Evelyn and her teacher friend traveled extensively throughout Europe. The rail system enabled me to visit Vienna and ski at the Zugspitze over a long weekend pass.

I returned to the states for graduate study in Civil Engineering at MIT and got a master's degree in 1957. Next was a two-year ROTC assignment at Alabama Polytechnic Institute in Auburn where I taught military engineer skills and shared my troop experiences. Then it was advanced officer training at Fort Belvoir followed by a non-dependent “utilization” tour in Greenland. That is, put into practice and pay back what I had learned in these two schools.

Greenland was a most unique experience. Initially I was Resident Engineer on a self-elevating steel communication/radar site for the Air Force about 200 miles from base camp at Sondrestrom out on the Icecap. Later I was Resident Engineer at site DYE-3 on the first Radome/Radar to be installed at the Ballistic Missile Early Warning System site near Thule. During that time I was able to visit the Army’s remote, completely underground (under snow) “city.” This was a self-sustaining research facility powered by a portable nuclear plant.

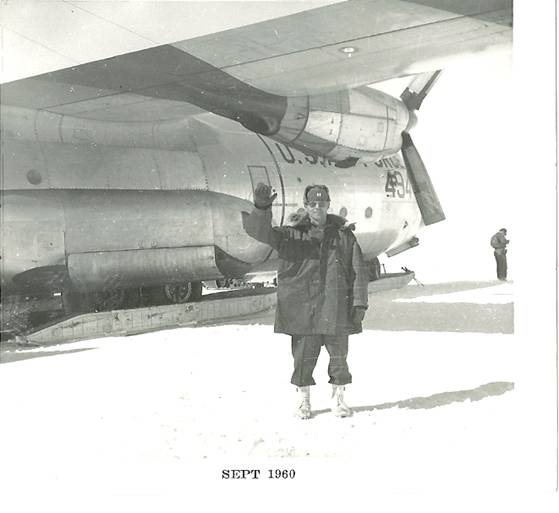

Here is a picture of me standing in front of the C-130 that carried supplies and equipment to us at the communication/radar site.

What special qualities and equipment did troops need to survive and work effectively under snow?

The special talents needed at Camp Century were in the construction of tunnels and building the complex. Swiss snow-milling machines were used to dig trenches and corrugated metal arches formed the roofs. Wooden buildings were constructed inside in a controlled temperature environment. Besides the living, working and maintenance areas there were common accommodations such as a library, gymnasium and theatre. Besides small ski-equipped airplanes, heavy materials were delivered by Caterpillar dozers pulling 20-ton sleds in a "train." The trip took two to three days.

A soldier at Camp Century near Thule, Greenland (1959)

An essential element of U.S. Cold War strategy was a credible deterrence both defensively and offensively; that is, early warning of an attack and a plan of response to an attack. I had three staff assignments involved with an area called General War Planning.

The first was in 1961 with the Strategic Planning Group in Washington, D.C. Its mission was to conduct studies for the Department of the Army, such as NATO capabilities. I assisted with maintaining the inventory of the six Army nuclear weapon systems. I authored a report on the survivability of the Pershing missile system in Europe. It was sobering to know each Pershing unit had the delivery capability four times that of Hiroshima. At that time, the UNIVAC-2 was the most sophisticated computer system we had. “Punched cards” were everywhere.

I'll never forget Memorial Day 1962. We were working and I got a call from Evelyn that her water had broken. The office was north of town and the hospital was south of town. I had heard subsequent deliveries come faster. This was our fourth, so I was quite anxious about a roadside delivery. Evelyn had to repeatedly remind me to slow down.

My second major planning assignment was to the Army Element of the Joint Strategic Target Planning Staff at Offutt Air Force Base, Nebraska. The base was co-located with the Strategic Air Command Headquarters (SAC). Our mission was to establish and maintain the Single Integrated Operational Plan for all Air Force and Navy nuclear assets. We worked in an underground command post. My personal responsibilities were to publish the National Strategic Target List and help with computer studies on damage assessments. By then, tape drives were available so we had stacks of printouts everywhere. We hardly had time to read them.

There was the pressure of continuous staff alert and immediate response. If an adverse intelligence report was received, it was “all hands on deck.” That meant colonels and generals too. Impressive teamwork. On a personal note, I remember the trepidation I felt as a young Army Major when I briefed Air Force 4-star General Thomas Power, Commander-in-Chief of SAC, on the probabilities of damage to the Soviet Union's hardened missile sites.

What were these damage probabilities?

In simple terms, probabilities were based on accuracy of intelligence and reliability and survivability of our delivery systems. To achieve a desirable level in the 90-95% range, it would mean redundant application of a combination of land-based missiles, submarine-

based missiles and air-delivered bombs.

My third major staff assignment was to the Missile and Nuclear Division at U.S. Army Pacific Headquarters in Honolulu. This meant participating in the Army component’s part of Pacific Command and providing Army members for Pacific Command’s Nuclear Surety program. This involved inspecting storage areas and nuclear-capable units throughout the theater.

One interesting sidelight was taking a secret helicopter reconnaissance flight over Laos to determine any “choke points” on the trail system used by the Viet Cong for possible interdiction with a small nuclear device.

Did you think this nuclear idea sound? If implemented wouldn't there have been a grave risk of the Soviets using their own nukes in Vietnam that might have led to world war?

The idea was sound purely from an “effects” standpoint in that it would create an area of contamination that would cause a major shift in supply lines from the north and provide more time to strengthen ARVN and US forces. Friendly forces were handicapped from the start in that the source of arms from the north was not really vulnerable as the enemy was in WWII. That is, there was no Inchon-type invasion of North Vietnam to neutralize the enemy.

As for the Soviets, I doubt they would intervene because there was no direct threat and the low yield weapon would be detonated in a remote and essentially unpopulated area. If North Vietnam would begin to fail, the real threat and major US concern would be massive Chinese forces swarming down the relatively narrow country as they did in North Korea. We know now that North Vietnam did not have expansionist Communist ambitions and that Vietnam is prospering again.

On a personal note, having grown up on the beach in Fort Lauderdale, I finally realized the dream of learning to surf on real waves. The good times ended, though, with another non-dependent tour. This time to Vietnam in 1969 for a 12-month tour.

In Vietnam I began with a desk job with the US Army Engineer Construction Agency Vietnam. I was charged with maintaining an inventory of Engineer personnel, equipment, and materials. I worked comfortably in a regular air-conditioned office, but I had to eat and sleep in the heat and humidity in temporary outdoor structures. Because of these daily changes, I couldn't shed a head cold for three months.

I recall that prominent figures came to Saigon and elsewhere in Vietnam to entertain the troops. I saw Neil Armstrong and Arthur Ash. (Buzz Aldrin, Armstrong's fellow moon-lander, is a West Point classmate). I also recall bi-weekly shipments of cookies or jelly from my dear wife.

After three months I became eligible for a troop assignment and was given command of the 864th Engineer Battalion with headquarters in Nha Trang. This duty had a sense of urgency and was most interesting and challenging. Our battalion had twelve company-sized units located in five widely dispersed sites up to 75 miles in two different directions from Nha Trang. We were authorized 74 officers, 1,562 enlisted men, and 395 non-military support personnel, but we operated at about 90% of these levels. Our primary mission was construction of one segment of QL-1, like our coastal US 1, and one segment of QL-21, an inland route.

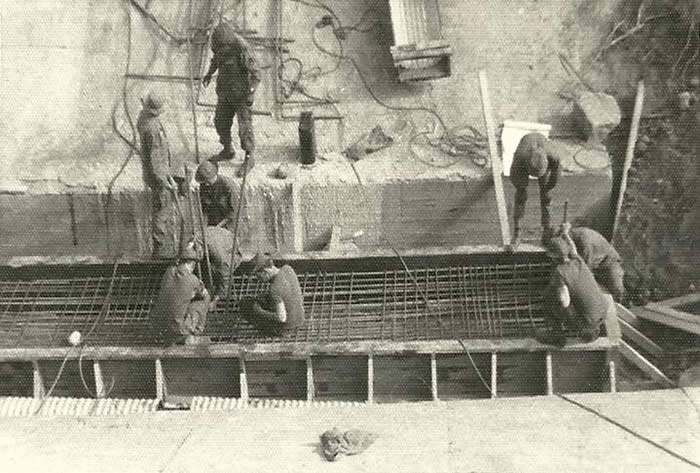

Men of the 864th Engineer Battalion erecting a pier foundation for Bridge 27 on road QL-1 north of Phan Thiet (January 1970)

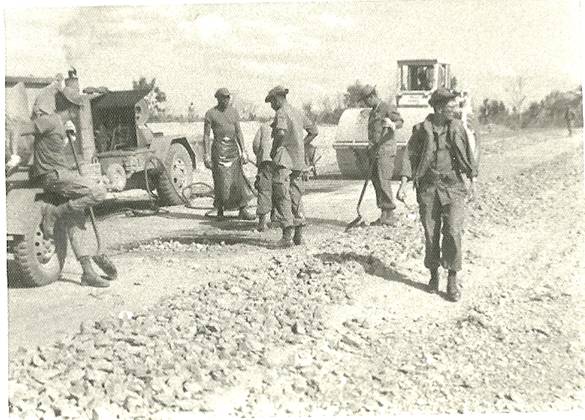

864th Engineers repairing a "pot hole" on QL-21 caused by a VC mine (1970)

We also supported South Vietnamese construction units with raw materials from three quarries. Our third job was supporting U.S. units with construction of bunkers and gun emplacements plus maintenance of small airfields.

Being located with II Field Force Headquarters in Nha Trang, our soldiers were scrutinized if they were off Post. One time I received a reprimand call that some of my men were observed riding in the backs of trucks with long hair and unkempt uniforms. Well, they had been living in tents in remote areas for extended time and were just returning to camp for some well-deserved R&R. I wasn’t going to worry about their temporary appearance.

Midway in my tour we had to relocate battalion headquarters to the quarry and road job further south near Phan Thiet on the coast. This involved movement by ship because roads were not secure between the two locations. We had to maintain a beach-transition operation for re-supply, set up a new maintenance operation, and expand the quarry site at “Whiskey Mountain.” My “living quarters” were a sandbagged CONEX container wired for electricity.

Why was it called "Whiskey Mountain"?

The mountain was the only significant land form in the coastal plain area of Phan Thiet. Presumably it was a convenient place to dig caves to store and protect contraband items such as liquor.

Ron Ely, one of the Tarzan actors, visited my site. I was of course responsible for his safety. He was willing to wear a protective vest when we left the compound but didn’t want to wear the steel pot helmet. These were the carry-over ones from WWII and still weren’t liked.

What were your main challenges in Vietnam?

One was keeping up with battalion operations at dispersed locations without the authorized helicopter. All air assets had been consolidated at higher headquarters and I had to “hitch a ride” whenever I could. So visits were brief if at all. I actually never got to visit one company site or even meet some of my officers.

Another challenge was the urgency of producing quarry products for South Vietnamese (ARVN) units as well as our own units and completion of asphalt concrete pavements. There was competition between commands. I did not enjoy having to personally give daily reports to higher headquarters late each night. We were also preparing to produce a lower quality but higher volume base course mix for roads.

I had to constantly make sure my men were safe and secure. For example, each day as they left the compound for the work site they used mine detectors on the access road.

Drugs and prostitution became big problems. At both Nha Trang and Phan Thiet, we were directed to open the compounds to Vietnamese nationals. You can imagine the consequences. One unusual incident involved two soldiers and a civilian bus. They noticed two women heading for the bushes for a “bathroom break” -- no Interstate Plazas in Vietnam. It was obvious what the soldiers had in mind. Remembering command responsibility and VD concerns in Germany, I cut short their plan.

Other major problems were the shortage of medical facilities and religious services. There was one dental visit in three months and no Chaplain visits. I made an attempt to lead Bible Study on Sunday mornings. It didn’t last long because Sundays were “stand down” time for maintenance of equipment and bunkers.

I had a number of positive experiences with the battalion. We had quality Reserve and Active Duty officers. They often had to operate pretty much on their own. Our senior enlisted personnel were excellent, especially those who understood road construction and maintenance of equipment. Also, we did helpful work for an assumed “soon-to-be free” Vietnam nation, such as “farm-to-market” roads and bridges. Since we were not working in an active combat zone, it was a delight to pass through villages and see happy children.

An interesting thing happened on jeep rides through villages. The children would gather around when we stopped. They were friendly and curious. Since Vietnamese don't have hair on their arms, they were intrigued by mine. I didn't know what they were saying when they stroked my arm. But I suspect their laughter implied "monkey."

How dangerous were the operations you were involved in?

In Long Binh the mortar attacks were at a distance. At Nha Trang the mortar attacks were small caliber and were not very accurate. They were short-lasting and bunkers were immediately available. I was most concerned when driving my jeep from the Post to my quarters near the beach around midnight each day. In May of '70 there was one minor attack on the construction compound at Phan Thiet. Some equipment was damaged but no casualties. I was not present at that time. I flew on over 25 helicopter flights over unsecure areas.

Did you feel vulnerable, fearful?

Vulnerable, yes. Fearful, no. I was there for a worthwhile purpose within my career path and I had a firm belief system. I also had strong family support from both sides of the family.

What is your belief system? How did it help you in Vietnam?

I accepted Jesus at Confirmation when I was about ten years old. That faith system encompasses all phases of life. It has not abandoned me, and I’ve had no reason to abandon it. Consequently, nothing I was doing caused a deep-seated concern. It has provided an increasingly greater comfort over the years, not just in wartime or during family separations. An unexpected benefit of this belief system was the waiting for the “right-for-me” woman to enter my life.

What losses did your unit suffer?

At Phan Thiet roadways and culverts were sometimes mined and three men were killed. Writing letters to the families was not something I was schooled in. You just open your heart. More disturbing was the loss of one soldier to drug overdose. How do you word that letter? I called a company meeting to point out the individual and enlisted leadership responsibilities of caring for each other as well as my general concern for their well-being. I remember saying, "If you don't care, I care and God cares." I have no idea if this session had any impact.

After my 6-month command I was moved to the 35th Group Headquarters as Executive Officer with three construction battalions and multiple company-sized support units. We were located at Cam Rahn Bay, a relatively safe area in another desk job with comfortable living conditions. My function was to keep the Colonel satisfied as he did all the traveling.

Did you have any personal contact with the Vietnamese?

Not really. Civilian males were hired for menial jobs in the mess halls and to assist the mechanics in the motor pools. Later on, women were allowed on the compound to do housekeeping chores. At Whiskey Mountain we provided rock products to ARVN Engineer units doing similar road work nearby and their equipment drivers would arrive to be loaded.

South Vietnamese civilians were rather stoic and ignored us, and we ignored them, mainly to avoid any unpleasant situations. The farmers and vendors would go about their business. Interestingly, in my battalion’s spread-out area, there seemed to be an unofficial "accommodation” with the Viet Cong. We remained relatively secure in our compounds during the night while they moved freely though the areas. Then they left us alone during the day while we built the roads and air strips they would use sooner or later. I recall my Pay Officer, a 2nd Lt. from Hawaii, was fearful of leaving base camp even though he could travel with other units in armed convoys.

My next assignment was a stabilized tour with my family at Fort Hood, TX in 1970. I was initially assigned to the Operations & Plans Division in a specialized organization. The title describes what it did: Modern Army Selected Systems Test, Evaluation and Review (MASSTER). We focused on specialized equipment for Vietnam-type operations.

After that I was assigned as Corps Engineer for the Army’s III Corps. The Corps’ main missions were to maintain the proficiency and readiness of Active Duty units for deployment, support MASSTER, conduct troop tests for the Department of the Army, and give Army Reserve units training opportunities. In one case an engineer battalion assisted with the construction of a golf course on post. Another mission was to support local communities with engineer projects. This included improving the shore of a nearby lake for recreation and earthwork to convert a low area into a pond for swimming. I had the use of one regular Engineer Construction Battalion to assist in these endeavors.

An interesting sidelight in this III Corps job was cooperating with the Fort Hood Facilities Engineer in support of the state funeral of Lyndon B. Johnson in Austin, TX and the burial at the LBJ Ranch in Stonewall, TX. Another sidelight was providing leadership for one of the Army’s Nuclear Emergency Response Teams. I was selected for training at Kirkland AFB in Albuquerque, NM.

My final job in the Army was Director of Plans, Training and Security for The Engineer Center and Fort Belvoir. This was essentially a peacetime operation in support of the Post, the Engineer School, and the Military District of Washington. It included providing troop support for small projects, providing a ceremonial band, operating The Engineer Museum, providing security clearances, and coordinating Reserve Component training. One unique task was planning complementary emergency communication and evacuation support for the President, which included an inspection of the lower levels of the White House.

Do you recall any special associations with other officers, including foreign officers?

Yes, and they were all in a professional capacity and congenial experiences. An Air Force weather officer periodically stayed with me at the DYE-3 site in Greenland. In December 1960 the building transfer (punch list) to the Air Force went smoothly. The Joint Staff assignment at Offutt Air Force Base in 1963-65 was obviously mixed. When I attended the Marine Command and Staff College in Quantico, VA, I studied and socialized with officers from the Air Force as well as Navy and Marines. The Nuclear Surety team in Hawaii was also represented by different services.

As for foreign officers, there were some in my Fort Belvoir class in 1959. I still keep in touch with then Capt. Manuel Rojas from Colombia, South America. There were also some foreign officers at Quantico. I made friends with Lt. Col. Yeo from South Korea.

I retired in July 1975 as a Colonel. Brigadier General James Johnson, Fort Belvoir Commander, presided. The awards included the Legion of Merit, the Bronze Star Medal, Meritorious Medal, Air Medal, Joint Service Commendation Medal, Army Commendation Medal w/Oak Leaf Cluster, Army of Occupation Medal (Germany), National Service Medal w/Oak Leaf Cluster, Vietnam Service Medal, Republic of Vietnam Gallantry Cross w/Palm, Air Force Small Arm Expert Marksman Ribbon, and Vietnam Campaign Medal.

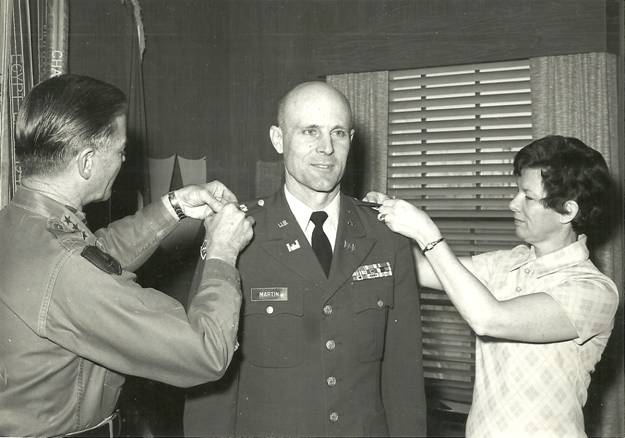

Jack Martin's promotion to full Colonel. General Seneff, CO of Ft. Hood, and Mrs. Martin are pinning on his eagles.

Looking back over my career, I would say a major challenge was meeting my own expectations and responsibilities associated with the West Point motto “Duty, Honor, Country." Then there was the balancing act of doing your job well, being a responsible husband and father and taking care of your own health. At times, priorities got confused and certain inconveniences disrupted that balance to the detriment of the family. Frequent moves so typical in the military have unknown impact on the education and personal character development of children. The impact on each one, positive or negative, varies each time based on the qualifications of the school teachers and opportunities at the installation.

Military service is a very worthwhile profession that requires unexpected and multiple sacrifices. It provides valuable character-development opportunities and provides unique travel and life experiences. I was fortunate to end on a positive note without battle scars. As for lessons of command, one was: learn to delegate duties. Also, make time to know your men better on a personal level. Often I found myself bogged down acclimating to each new job and chasing details.

There’s a decision time to retire. For me, it was 24 years to provide better stability for our younger three children. I moved the family to Gainesville with five goals: career switch to teaching, provide a stable life and help our boys through college, support youth sports activities, pursue my love of handball and find a retirement home. Of course, Evelyn and I continued our commitment to church life.

I got a Masters in Education at UF and then a teaching position with the UF School of Building Construction. The transition was easy. Education was a part of my Army career and I was teaching subjects related to my Civil Engineering background. I was Teacher of the Year for the College of Architecture in 1982-83 and retired as Associate Professor Emeritus in 1990.

In-state tuition was a big help as all five sons attended the University of Florida. I continued coaching age-group divers. I was also a recruiter for Modern Pentathlon and provided scholarships for boy and girl athletes to attend the Olympic Development Center in Roswell, NM. Also, I was able to team up with a retired Navy dentist to win state and regional handball events in our “golden” age group.

Evelyn and I will spend our remaining years in Gainesville, FL in the Oak Hammock retirement community. Life is good.

Richard (Dick) Martin graduated from Duke University Divinity School and ministered at churches in Scotland and Virginia. In 1962 he entered the U. S. Army as a Methodist chaplain. In 1986 he retired from the Army with the rank of colonel and then joined the staff of Hyde Park United Methodist Church in Tampa, Florida, where he directed senior adult ministries. In 2007 he and his wife Patricia brought their community spirit and expertise to Oak Hammock at the University of Florida. Dick has been using his video skills to help build a library of DVDs documenting many important activities at Oak Hammock. He also conducts Oak Hammock religious services as a volunteer. Pat has been doing beautiful needle work, contributes regularly to the community's newsletter, and volunteers in the Outpatient Clinic. Dick and Pat are the parents of three daughters and have three grandchildren. In the story below Dick talks about his vivid memory of an instance during World War II, how he came to be an Army chaplain, some of his experiences with a combat division during the Vietnam War, and major Army assignments he had after the war.

I was just a young kid in World War II, and I had an older brother who was in the Army. He went to OCS [Officer Candidate School] and became a tank commander in North Africa with the Second Armored Division in Patton's Seventh Army. Everybody was worried. We'd hear about the dangers. There was this helpless feeling because you didn't know what was going on. The only news sources we had then were the radio and newspapers. The news was very slow in those days. Something could have happened two weeks ago and we didn't even know about it till much later.

I have one vivid memory. I used to sleep upstairs on the second floor of our farmhouse and I remember several times waking up in the middle of the night, and I would hear my mother down on the first floor pacing around and humming the tunes to some of the old hymns. And I guess that was her way of dealing with my brother being in harm's way. Because she just didn't know. We were all dealing with uncertainty in those days.

But my brother came home safely. He was so happy to be home. He was like many combat veterans; he never talked about the war. He went to college on the GI Bill and got his master's in agronomy.

I had a deferment while in college and the idea of the military never occurred to me then. After seminary, I spent a year in Dumfries, Scotland, as Assistant Minister of St. Michael's Church and returned to Northern Virginia to become minister of Charles Wesley Methodist Church in McLean, Virginia. I had a lot of military people in the church and they started talking to me about the chaplaincy. So I began to investigate that as a form of ministry. After four years at the McLean church, I sent in my application. I had a colonel in the congregation and he sort of walked me through the Pentagon.

My first application came back and said I was medically disqualified because half my left thumb was missing. I'd hurt it as a kid chopping wood. That doesn't seem like much of a disqualifier (Laughs). But there was something in the regulations that says that if you're missing part of a finger you're disqualified. (Laughs) The next day I called this colonel friend and told him about being disqualified. He said, "Aw, I'll take care of that!" So I got a waiver. We had a three-year commitment. My first thought was to spend three years and then go in the Armry Reserve. But I got in, Pat and I liked the active Army, and we decided to stay.

I went in as a first lieutenant. Later they started bringing in chaplains, doctors, lawyers and professional people as captains. I had a wonderful career. My first assignment was with an engineer battalion at Ft. Meade, Maryland. That was 1962, just as the Cuban Missile Crisis was heating up. About a month after I got in, we were on alert to go somewhere and do something. We didn't know what. I didn't even have my security clearance yet. The commander just said, "Pack your stuff and be ready." But we didn't go anywhere. I thought, umm, this may not be all that I had planned for. (Laughs)

I had some great assignments. I enjoyed the troop assignments. At Ft. Meade I was a battalion chaplain. By the time I got to Vietnam I was a major and became brigade chaplain. Later on, I went to Korea as a division chaplain, and then I ended up as the U.S. Army Europe chaplain. So the troop assignments are good because you spend time nearly everyday with the troops. I had my share of administrative things. I was an assistant post chaplain, I was on the faculty at Ft. Leavenworth, and I was in the Chief of Chaplains Office in Washington, D.C. So you do your time, but you always like to be with the troops.

I spent a year in Vietnam with the 25th Infantry Division. Our division headquarters was at a large base camp at Cu Chi about 40 miles north of Saigon. I didn't spend a lot of time there. I spent most of my time out in the jungle because that's where our troops were. To get their respect a chaplain had to be with them in the field and share the dangers of combat. Otherwise they wouldn't talk to you. I hopped around from unit to unit and caught a ride on any helicopter going my way. At each unit I conducted Protestant services. I usually announced the service at evening chow. There was no safe place in Vietnam. Each unit had a temporary base camp, and for the service we had something like a protective perimeter. The guys would all be in combat gear, flak jackets and helmets. They'd sit on the ground and have their weapons beside them. I would unpack my chaplain's kit, about the size of a backpack, and start the service. I kept it short, about 15 or 20 minutes, because the soldiers had duties to perform. We sang hymns and I gave a brief homily; then I offered Communion to those who wanted it. Most of them did. At the end of an operation I was choppered back to division headquarters and we had steaks and drank beer and got ready to go out again.

In this picture I'm holding a service in the field. To my right on the stand are the cross and Communion chalice. This situation was more relaxed than most I was in. There was no immediate danger. That's why the soldiers didn't have their helmets on.

![Description: C:\Users\Owner\AppData\Local\Microsoft\Windows\Temporary Internet Files\Low\Content.IE5\G4ISU1AL\VIETNAM-1968[1].jpg](images/clip_image002_005.jpg)

Were your missions primarily search-and-destroy?

The troops called them "search-and-avoid." (Laughs) Troops have a label for everything. Sometimes they didn't avoid; we did discover things. The 25th Infantry Division is nicknamed "Tropic Lightning"; their insignia has a little lightning figure. It was a good division. They had battalions of regular infantry, and they had mechanized units. I was with a mechanized battalion. They carried 50 calibers [machine guns] on their APCs [Armored Personnel Carriers]; they rode rather than walked, and that was much, much better. (Laughs) Usually I went out with a company that had mortars and a couple of tanks. Our long range artillery stayed farther back in the compound.

Were the tanks that mobile in the jungle?

It's amazing how they'd get through; they'd just knock stuff down. Sometimes they'd get bogged down in a swamp because the weather was a lot of rain. Then they'd have to bring in equipment to get the tanks unstuck.

Besides conducting services, what were your other responsibilities in the field?

I was just there with the troops. We called it “ministry of presence.” My primary responsibility was to provide spiritual care for soldiers. I did a lot of counseling, lot of responding to troops who'd come up and say, "Can I talk to you for a minute?" So somebody's got to unburden something, you know. Almost every day I was in Vietnam I had some kind of short service somewhere. And I served Communion at every service. This was a sober time.

What kind of counseling did you do?

I counseled guys who were depressed or frightened, got a "Dear John" letter, or found out things weren't going well at home--just everything. I'd hear problems like a soldier felt he was getting a raw deal, or this sergeant was being too tough on him, or his pay got messed up, things like that which usually got straightened out. You know how rigid the chain of command can be. You take your problems up through the chain. That's one of the rules.

The chaplain was not in the chain of command. A soldier could go to the chaplain and say, "I want this to be confidential," and there's no way in this world I would ever divulge that. Now if I saw trends going on, and I kept hearing the same story, I'd go to the commander and say, "I think we ought to take a look at how this is being organized or what's going on here." For example, if soldiers traveling around continued to get their pay messed up, and people back home relied on that pay allotment, and I kept hearing stories like that, I'd say to the commander, "We need to do something about this pay thing." And he'd look into it and get it straightened out.

One of the 50 stories in a recent book on military chaplains is your own story about officiating at a funeral for a soldier in Iowa.* In it you mention sharing some deeply spiritual moments with soldiers during your jungle church services. Would you give an example of such a moment?

When a soldier got up enough courage and said, "Can I talk to you?" I considered that a spiritual moment. It wasn't necessarily a religious moment per se. Sometimes it was. Some of these kids had been very faithful in their church and were wondering how they could hang on to that in the midst of all this stuff going on. Some soldiers seriously questioned whether they could participate in the war. They were not from a so-called peace church, but they were beginning to have doubts like "How can I kill this person?" When we had a long talk about it, that was a spiritual moment.

Did the protest movement influence a number of soldiers?

Not much. Not in 1967-68. I think later on as the war wore down that became a bigger problem. They were aware of the protests. We'd get letters from home and they'd see stuff in the Stars and Stripes. But soldiers are more concerned about survival than anything else. And they want to get home. Let me survive and let me get home.

What was some action you were directly involved in?

We rode in APCs. An APC held seven or eight men. We had a doctor in our battalion. He had his own APC with supplies, stretchers and other medical things. During the day I rode on an APC with the troops. At night I bunked in the doc's APC. An APC was made for soldiers to ride inside; supposedly the armor would protect you. But the Viet Cong had these armor-piercing grenades; they were almost like homemade weapons but very effective. They'd pop up out of a hole and fire the thing through some kind of bazooka-like device. We went back to Vietnam a couple of years ago--first time I'd been back--and we visited a place where they had a display of homemade weapons, just simple little things but they could do a lot of damage. When we went out on a mission, guys would ride on top of the APC. If you got hit by an armor-piercing grenade, you'd get blown off but not killed. The APC driver was the most vulnerable of all. We lost more drivers than anyone else.

One day we came into a large clearing and ran into a big ambush. We got hit bad; stuff was flying everywhere; our soldiers flew off the tracks and were firing in all directions. We hunkered down and had sort of a perimeter. I looked up and there was a soldier lying out there in the clearing. I just took off and went out there and got him. He was in very bad shape; I won't even describe how he looked. He later died in my arms. I remember him very well. He was a great young Catholic. He was one of the guys who'd round up Catholics when we had religious services. Whenever possible, I would travel with a Catholic chaplain. We would share the first part of the service; then we would separate so he could serve the Eucharist and I could serve communion. It was a great arrangement.

But when this soldier got hit that day there was no priest around. We had only one medic in the company, and he was busy patching up somebody else. The soldier was calm, probably in a comatose state. But his eyes were open and I thought, Maybe he can see and maybe he can hear, so I talked to him and prayed with him. That was the best I could do. We got him on the chopper; then the medic showed up. But the soldier was gone. I ministered to many wounded soldiers and some died while I was with them, but this young man was the only one who died in my arms. I'll never forget him.

![Description: C:\Users\Owner\AppData\Local\Microsoft\Windows\Temporary Internet Files\Low\Content.IE5\FUEKP0S1\Vietnam%201968-8[2].jpg](images/clip_image004_002.jpg)

Chaplain Martin conducting a memorial service for fallen soldiers at the 25th Infantry Division base camp at Cu Chi, South Vietnam ca. 1968

How did you feel rushing out during the battle to get that soldier?

There was no sense of danger. I don't know how to explain it. If I'd thought about it, I might not have done it. It was just something that needed to be done. There was nobody else around him and this guy needed help so I tried to help. It was an instinctive reaction.

I was in other combat situations but not quite as serious as this one. We had enough firepower. These small Viet Cong units didn't want to engage. Once the engagement took place, they'd escape into the jungle and down into tunnels.

How did you get the Purple Heart?

I got a little shrapnel in my arm here (Shows right arm) and the medics patched it up. It was nothing compared to the really bad wounds some guys got. I felt guilty getting the Purple Heart for this, but once you are treated by the medics you have no choice.

How did you reconcile your devotion to the non-violent ideals of Judeo-Christianity with your service in the Army and its violent objectives and tactics?

That's something every person has to work out, I think. My overriding concern is the church needs to be where people are. And if they have to be in combat, the church needs to be there. So that was the motivating thing for me. There are others who could not get to that point and chose not to do it; that's okay. But I didn't really have a problem with that. I'm a just war person. I do think there are criteria about any war that need to be examined. But once we get in there, a soldier doesn't have any choice. He's just sent there. So the church needs to be there too. It's a constitutional thing as well. A person has the right to freely exercise his faith. So that's partly what we were doing, giving people a chance to exercise their freedom of religion.

How was morale in the 25th?

Pretty good. Part of the chaplain's job is to be sensitive to morale. That's what the commanders want us to do because we're on the ground with the troops. Commanders are wrapped up with many other things. So chaplains are their eyes and ears. Chaplains can answer questions for commanders like, what's going on out there? Commanders would be sensitive to the fact there were times when we needed to go back to the base camp, rest up, and get regenerated. Chaplains pretty well monitored things like that.

Food was very important to soldiers. It's hard to believe, but we'd be out in the middle of the jungle, and we'd usually have one hot meal a day. They would fly it out to us from our base camp at Cu Chi. We got steak and ice cream all running together. (Laughs) One hot meal a day really helped morale. Also, soldiers would store things in APCs. There was a lot of space in there for ammunition, but they'd also put other things in there: K rations, ice, sodas, and stuff they got from home like cookies and crackers. We'd be in the jungle and stop for lunch and start breaking out all these things and have some pretty good meals. (Laughs) Food was never a problem.

Any drug problems?

No. We had a few alcohol problems. Guys would sometimes drink too much when they got back in base camp. Drug abuse came later when the war was winding down.

Desertions?

The guys I was with were busy every day. They had no time to desert. They were just trying to survive. Soldiers look out for each other. The guy on your right, the guy on your left, they're friends; they're the ones that protect you. There was the feeling in those small units: I don't want to let this unit down. And that's the reason so many guys did so many heroic things. They would do some amazing things just for their buddies. If one of their buddies got shot, they would run out there and sometimes they got shot, too. They wanted to look out for their buddies. Desertion would be letting your unit down.

What were your impressions of the Viet Cong?

When I first got there I thought, This thing can't last much longer. We had such overwhelming firepower, total air superiority. So I thought we ought to be able to wrap this thing up in a couple of weeks and go home. But the Viet Cong were just tenacious, and we never quite figured out how to deal with that. Their whole underground system of tunnels and underground hospitals; they just lived underground. We had guys called "tunnel rats" that would go down in those tunnels. It was said the VC had tunnels underneath our division headquarters, but I'm not sure about that. I don't think we understood how tenacious they were or how to operate in an unconventional environment. We had all the stuff for conventional warfare, but it took a while to figure out that we were dealing with an unconventional situation.

The Viet Cong used a lot of mortars. I remember being at a temporary base camp north of Cu Chi. I'll never forget the 4th of July when a thousand rockets came into our base camp.

The Tet Offensive in '68 was the turning point. That's when we realized that this thing is not going away. I was out in the jungle then, and my battalion was transferred to Saigon. I spent some time in Saigon after the Tet Offensive. Tet was a military failure for the communists, but it boosted their morale. Once the North Vietnamese got into it, they thought they could do pretty much anything they want.

What did you think of the ARVN? [South Vietnamese Army]

The ones I saw were pretty effective. I talked to some advisers and they thought the ARVN were pretty good soldiers. They needed a lot more training than they had. It was a difficult situation because they were fighting their own people. It was a little hard sometimes to get the ARVN to really go strong, but probably did the best they could.

After the Vietnam War I had some great experiences at the Command and General Staff College at Ft. Leavenworth. There was only one chaplain on the faculty. I first went there as a student taking courses in tactics and military things like that. When I graduated, they asked me to stay on the faculty. I was on the faculty from 1975 to '79. It turned out to be a really great assignment. I met some great officers coming through there and met up with many of them later on. The training doctrine was changing at that time, and the Army was beginning to teach in small groups. The Army had finally discovered that a lot of learning could occur in small groups instead of standing up there on a platform with an overhead projector and saying write this down. We had some lectures, but most of the instruction was in small work groups.

The first course I wrote for the Command and General Staff College was a course in Group Dynamics, how to operate in small groups. Like most instructors,I wrote as well as taught at the College. We had to write what we were teaching and write the exams for our resident students and also send the material out to non-residents. That was the drudgery part; the fun was teaching. The whole first day of class for resident officers was devoted to Group Dynamics, and that was my course. We talked about effectiveness rather than good and bad, how can you work effectively as a leader, how to listen better, and other leadership skills.

Then I helped to develop an elective, sort of a catch-all thing, called Human Resources Development. It dealt with communications. It dealt with ethics. The military was just beginning to talk about ethics in those days because there'd been some serious issues. This elective was very popular, so we had a whole bunch of sections taking it and a bunch of instructors. We had a lot of students from other countries who were our allies. We had Israelis, Saudis, and other foreign nationals. We had an officer from Saudi Arabia who was a prince. He came to my office one day and said, "I would like to transfer to another section, if it's okay with you." The computer had matched him up with an Israeli officer, and he didn't think that would produce the best learning environment. (Laughs) But it was interesting to me that he took the initiative, "Reassign me. Don't reassign him." And it worked out fine.

Leadership, team-building, ethics and communications, the soft subjects, were all grouped in the Human Resources course. Some students, the hardcore guys, thought these courses were stupid. They'd call them "touchy-feely" and stuff like that. But a lot of students got into it and found a lot of value in learning to listen and figure out what's going on because every one of these people was going to have staff and command positions later on. And the College was a perfect laboratory to work on these things in a non-threatening way.

There was an instructor in all these peer groups. We didn't turn them loose on their own. And the instructors gave constructive comments. The idea was to build up the whole peer group. Students started helping each other. The students were mostly majors and a few senior captains and junior lieutenant colonels. Basically they were middle managers.

Besides Vietnam, what's your overall opinion or impression of the Cold War?

My last assignment was in Europe at 7th Army Headquarters in Heidelberg. That was '83 to '86. The last half of my time in Europe I was also the U. S. Army Europe Command Chaplain. That's the U. S. component of NATO. So I had two hats. Constant training was taking place. The situation was relatively calm, but the Soviets were on the other side of the border, and we had troops all around that border. We had a number of alerts, had to get up at 4 o'clock in the morning. I was impressed with the constant sense of urgency. Our forces had different scenarios: the Russians would come through the Fulda Gap and other possible Soviet attacks. We would war-game those things and get down on the ground and train for all that. I was really impressed. We never really got complacent. What part that played in ultimately having the Cold War come to an end I don't know, but it must have had some impact.

![Description: C:\Users\Owner\AppData\Local\Microsoft\Windows\Temporary Internet Files\Low\Content.IE5\PNEHJLNK\USAREUR-1986[1].jpg](images/clip_image006_004.jpg)

General Glen Otis, then Commander-in-Chief of U.S. Army, Europe/7th Army, Chaplain Martin, Pat Martin. The general had just awarded Dick the Distinguished Service Medal.

What was the funniest experience you had in your military career?

What can I say? Everything is funny. (Laughs) Soldiers make fun out of everything. In Vietnam I would have my services usually after the evening meal, just as it's getting dark. Frequently at night we would get mortared by the Viet Cong. Shells would come flying in and hunker us down in holes our guys had dug. I'd usually have a service not too far from one of those holes. I went through a whole series of evenings when, just as we would get going on the service, here would come the mortars, so we would jump down in the holes. (Laughs) After several of those episodes, one guy said, "Chaplain, I think we ought to change the benediction. It ought to be In the name of the Father and the Son and in the hole we go.” (Laughs)

Did you spend time on the border between East and West Germany?

Our headquarters was in Heidelberg, but I would visit the troops on the border from time to time. Pat and I spent a memorable Christmas Eve out there one year. I was always impressed by the sense of vigilance among our troops.

I have a border story for you. The last six months I was in Europe, the commander got a request from a local television station. They wanted to do a documentary about the religious life of the American soldier. Unusual, but it seemed OK. The Chief of Staff told me, "We'll approve this as long as you go along. Don't let them out of your sight!" (Laughs) The crew consisted of a reporter and a camerman from Norway. I’m sure they were looking for something sensational, but, in one instance, they got just the opposite. One day we were out near the border having lunch in a mess hall. After lunch, the reporter, who spoke beautiful English, saw a soldier sitting at a table with a Bible in his hand.

Reporter: I see you have a Bible.

Soldier: Yes, sir, I take it with me any time I can.

Reporter: Would you be willing to be on camera? I'd like to talk to you about that.

Soldier: Sure.

Reporter: This Bible you have, it says in there that you should love your enemies. Do you love your enemies?

Soldier: Yes sir. I love my enemies and I pray for them every day. I pray that someday these walls will come down and we will be able to live in peace. But, until that time comes, I am a soldier and I will do my duty.

I went to Norway to assist in editing that film and to insist that the soldier’s comments be included. I often wondered what the people in Eastern Europe thought when they saw that young American and heard those words: “I love my enemies, I pray for peace, but until it comes, I am a soldier and I will do my duty.” That sums up the religious life of one soldier in Europe in 1986.

DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY

HEADQUARTERS 25th INFANTRY DIVISION

APO San Francisco 96225

GENERAL ORDERS

NUMBER 1403

20 March 1968

AWARD OF THE BRONZE STAR MEDAL FOR HEROISM

MARTIN, RICHARD K. OF104250 MAJ CHAPLAIN USA

HHC, 2nd Bde, 25th Inf Div

Awarded: Bronze Star Medal with "V" Device

Date action: 24 January 1968

Theater: Republic of Vietnam

Reason:

For heroism in connection with military operations against a hostile force: Chaplain Martin distinguished himself by heroic actions on 24 January 1968, while serving as Assistant Brigade Chaplain accompanying Company C, 4th Battalion, 23rd Infantry, on a search and destroy mission in the Ho Bo Woods, Republic of Vietnam. Company C was savagely attacked by a Viet Cong Force with 2.75 inch and RPG rockets. Within minutes of the initial contact there were many casualties scattered over the battlefield. Seeing the need for assistance Chaplain Martin voluntarily went from casualty to casualty, repeatedly exposing himself to intense hostile fire, to provide spiritual and moral support to the wounded and dying. With complete disregard for his own safety he led wounded personnel to the medical evacuation area and helped with their evacuation. Through his personal courage and outstanding leadership he was an inspiration to others around him. Major Martin's personal bravery, aggressiveness, and devotion to duty are in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service and reflect great credit upon himself, his unit, the 25th Infantry Division, and the Unites States Army.

Authority: By direction of the President under the provisions of Executive Order 11046, dated 24 August 1962, and USARV message 16695, 1 July 1966.

FOR THE COMMANDER:

B. F. HOOD

Colonel, GS

Chief of Staff

OFFICIAL:

CLARENCE A. RISER

LTC, AGC

Adjutant General

* Dick's touching story "A Mother's Photo" appears in Miracles & Moments of Grace: Inspiring Stories from Military Chaplains by Nancy B. Kennedy, Leafwood Publishers, Abilene, Texas, 2011.

|