|

Frank N. Pierce and his wife Jo Ann are founding members of Oak Hammock. A few days before our interview, Frank invited me to their apartment to see his Navy materials. In the corner of the sun room sits an exquisite model of the USS Mattaponi, AO-41, the fleet tanker Frank served on for nine months, 1946 – 1947. “It was made by a man in St. Louis, Michigan. I bought it in 1994 for $5,000,” Frank said of the model. He then showed me albums containing vivid photos and writings he did during his naval service. For 14 years he has been editor and chief writer for On Station, a newsletter detailing the history of the Mattaponi. After military service, Frank graduated from The College of Wooster with a major in Liberal Arts and from the University of Missouri with a M. A. degree in journalism. During 14 ½ years in business, he worked in professional advertising with Kroger Company, J. Weingarten, Inc., Crown Zellerbach Corporation, and Grant Advertising. At the University of Illinois, he got his doctorate in mass communication with a minor in marketing. He taught advertising at the Universities of Illinois, Texas, and Florida. The last 22 years he spent at UF where he served as the first Chairman of the Department of Advertising. I interviewed Frank in Oak Hammock’s Meditation Room on March 26 and April 3, 2010. He later provided more written information for this history.

My mother was a Quaker; my father was a Methodist. We lived in Lake County in Northeastern Ohio. Before the war, my family had been Republican and isolationist. At that time, we really didn’t want to get involved in foreign affairs. We didn’t know anybody who’d been to Europe. We wanted to mind our own business and wanted Europe and other countries to mind theirs.

I had one year at The College of Wooster before I was drafted in May 1943. I finished electrician’s mate service school and was assigned to the Naval Air Technical Training Center (NATTC) in Jacksonville, Florida. This place was not popular with a lot of guys. Some called it “a horseshit base.” I liked aviation electricians mate (AEM) work better than just electricians mate work. I was always interested in weather, kept weather records for many years. I wanted to be an aerographer, but the Navy needed electricians. The thought that I might be buried inside some ship somewhere doing electricians mate work didn’t excite me at all.

I was motivated to take the officer candidate test because the Navy promised a college education and a commission. About 300 men took the V-12 test at NATTC in March of 1944. Only twenty of us were selected to be sent to a college that offered the V-12 program. By then I was a Petty Officer 3rd Class. No one else in my AEM unit took the test. All the other members of my graduating AEM unit were shipped to California naval bases or assigned to aircraft carriers in the Pacific. For three weeks I was the only one in my barracks. I was awaiting orders and did a little reading and some writing to pass the time.

In the Navy’s V-12 Program

In 1944 the war was going pretty well. I certainly felt I already had a hand in it because I’d been in service for 13 months when I was assigned to the Navy’s V-12 program at Denison University in Granville, Ohio. I now had a chance to become an officer and this pleased me significantly. I’d be able to put my education thus far into practice while becoming even more educated. I spent three terms at Denison. Each term was four months. Half of all courses were assigned by the Navy. Others were electives. My professors at Denison were civilians, but the Denison V-12 Program was generally similar to the curriculum of the first two years at the Naval Academy. I took six or seven courses a term, including liberal arts courses and one in propaganda analysis. Two Naval Reserve officers in command of our V-12 unit made certain each man’s selected courses fulfilled the Navy’s educational requirements. We were under naval discipline at all times. At Denison I also lettered in baseball as an outfielder.

What did the propaganda analysis course entail?

We studied how propaganda praises things and manipulates opinions. We examined enemy propaganda, mainly the Nazi kind. We read Goebbels’ speeches in English and wrote papers on how to combat his tactics. I remember after Germany surrendered seeing pictures of brutal Japanese. One said, “Remember me? I’m still here.” I had the feeling that we were being prepared to invade Japan.

I was too young to know about propaganda then, but I recall posters of Japanese stuck on telephone poles; they looked scary, like monsters. How did you feel about the possibility of being part of the invasion of Japan?

Germany was still going strong in 1944 despite the Allied invasion of Normandy; Japan still seemed extremely resilient. We and our allies seemed fairly likely to be the final victors. But when? All we knew was that Japan would have to be invaded just as Germany would have to be invaded. I don’t really believe I thought much about what part I might play as time moved on. I had a lot of hard studying ahead of me and I better get cracking on it if I wanted to remain in the program.

NROTC at Harvard College

After Denison I was sent to Harvard where I was taught by naval officers. I spent another three four-month terms of NROTC training [Naval Reserve Officers Training Corps]. My group was training to be Navy line officers, and we stayed together in a dormitory, Eliot House. Half of my Harvard courses were Navy ones. I took Seamanship I and II, Navigation I and II, a course in damage control, and one in ordnance and gunnery. I took two courses in creative writing, one in poetry, one in stratigraphy (a geology course about rock layers), one in meteorology, and a course in piano terminology. I played on the Harvard baseball and basketball teams (the B team in basketball). I didn’t letter in the sports because the College ruled that Navy men played on “the informal sports teams” that academic year. That was the only year that Harvard has been invited to participate in the NCAA men's basketball tournament.

My favorite course at Harvard was a writing course taught by Professor James B. Munn. The course had 15 students. Two of us were Navy men, one student was a reporter for the Boston Globe and one was a stringer for Time magazine. Professor Munn lived in a home near where Washington took command of the Continental Army. The greatest accolade Munn could bestow upon an individual was to read aloud all or part of a piece a student had submitted. He read a portion of one of my stories. I walked out of the class ten feet tall. It was one of the greatest feelings I’ve ever had. Professor Munn and I corresponded for more than 20 years afterward. He and another creative writing instructor at Wooster are the greatest teachers in my experience.

In June 1946 I received my commission as an Ensign in the Naval Reserve. I was assigned to the USS Mattaponi, AO-41. AO means Auxiliary Oiler. Before the Navy got it, the Mattaponi had been a Standard Oil ship, the SS Kalkay. After she was taken over by the Navy, the Mattaponi became the 41st tanker in the Navy's consecutive numbering system. Its most common name was the “Mattie.” In the summer of ’46 we called her “Mad Mattie” because things often went wrong. There was always a problem in the engineering area. All the ships had problems. They got beaten around by waves. Water lines break; hatch covers freeze shut or pop open unexpectedly; hawsers and wires break, electrical problems darken the ship unexpectedly, etc. When we were coming into the Port of Naha,Okinawa, the anchor wouldn’t drop on command and we damaged our propeller on a coral reef before we could stop our momentum.

During the Vietnam War the ship was called the “Angel of Market Time.” “Market Time” was the name of a naval operation during that war. The Mattie participated in it as one of several oilers replenishing U.S. destroyers, cruisers, and carriers then patrolling the coasts of Vietnam.

During my time as the ship’s navigator (July ’46 – April ’47), it was one of ten oilers involved in transporting Saudi Arabian diesel oil, lubricating oil, and gasoline to Far Eastern ports. This Saudi Arabian oil contract lasted from June to December of' '46.We made two round trips of 14,500 miles each. The first trip was from Yokosuka, Japan, to Ras Tanura in Saudi Arabia and back to the Asian ports of Buckner Bay and Naha in Okinawa. The second trip was from Japan to Saudi Arabia, then to Manila in the Philippines. During my time aboard the Mattaponi, she steamed 36,000 miles in the Pacific and Indian Oceans and the Persian Gulf. One stop we made was at Eniwetok Island. We picked up an empty gasoline barge there, towed it 2,000 miles and dropped it off at Pearl Harbor without stopping. In all, the ship made three trips then from Japan to Saudi Arabia and back to Far Eastern ports. I was on the latter two of these three trips.

They that go down to the sea in ships, that do business in great waters.

(Psalm 107:23)

I was happy to be in navigation. Four of us ensigns had to keep journals. We were assigned certain topics like making diagrams of fire-fighting systems, piping, storage places for sea water and distilled water, etc. Our journals were judged for accuracy by two officers. However, the Navy didn’t afford me enough creativity. I was in foreign places and wanted to be a foreign correspondent. My private writings aboard ship consisted of descriptions and impressions of people, places, and things. I wrote detailed letters home. Here are some examples. You can keep them if you wish.

A passage from Frank’s shipboard writings, mid-January 1947:

However far a ship may wander over the trackless waters of the earth, men guide her course. Men chip her rust and swab her decks. Men splice her lines and air her flags. Men cook her meals, clean up afterward, launder her clothes, distill her drinking water, tend her boilers. Men guide her helm, stand her watches, and record the events of each watch in the log. Men nurse her engines, and treat her sick and wounded. Men plot her position at every opportunity, and inform her captain. Men deplete her supplies, read her mail, speed her up, slow her down. Men stagger under her motion and curse her for any reason. Men sleep on her, tell stories in her wardroom and mess halls, wash their faces, shave their beards, work at her desks, bang her typewriters. Men man her radars, her guns, her directors, her control stations, her fire stations, her collision quarters. Men muster aboard her after the dark is gone. Men spin her valves, check her draft, pound her nails, connect her hose lines, operate her winches and boats. Men leave her on liberty and come back.

A ship is a world. Men live on her.

I wrote a long letter to my family at Christmas time in 1946. I wanted to give my parents, brother, and sisters a sense of what my shipboard life was like as we sailed past Bataan and Corregidor and steamed into Manila Bay. I really tried to think of them as aboard with me as my shipmates and I reached the end of an arduous journey.

Four parts of Frank’s December 26, 1946 letter from Manila to his family in New Concord, Ohio follow:

Dear Folks,

For you back home it is Christmas with snow falling and a cold wind from the north whistling around the house and a gray sky lowering. For you it is Christmas, with presents and love and good wishes and being remembered by your friends as well as by the other members of the family. For you there is a warm feeling inside as you think how lucky you are in comparison with some other families and other communities and other nations that you know of. For you the wind is not through the room, but outside it; while many families know the opposite.

For you there is food on the table, and laughter, and women, and the house across the street. For you there is the hill with the snow blowing down it, a frosty window, and perhaps a Christmas tree. And there is the thought of the future—perhaps only tomorrow night, but at least a future with each one of you in it—and a genuinely terribly-needed feeling of togetherness as one unit, one group.

The presents were opened today. Dad got a few small items—the usual lot of a father because he is the hardest member of the family to buy for. Mom got more and the children more yet—because they are easier to supply with useful gifts. Perhaps there was even a present for me laid under the tree, to be opened when I get home. Perhaps not, but it makes no difference.

Today it is the day after Christmas in Manila. It is hot, over 90 degrees, and still. The cool breeze never blows here, and never will. The snow never reaches the ground. There is no house across the street, no hill with the snow tumbling down it, no frosty glass, no Christmas tree. There is no family on ship, and there are no presents. But there is one exception.

Every man on board got the only Christmas present he ever expected out here. Every man on board is now happier, his morale has gone up temporarily once more. Because the mail came in today.

Not since we left Yokosuka on November 15 has there been any mail. No one missed it at sea. Everyone thought about it occasionally, but no one really missed it. There is no way to get it to us there. But in port it is different. In port the mail should come. And if it does not come, everyone gets mad. Today the mail came on board—but only six sacks for six weeks. It is not all of it, but it is something. I got 15 letters from many of my friends, and letters from you. It was very nice to read your handwriting again and find out what has been going on in that crazy country about a hundred thousand miles away. It was my Christmas present—the best one there is….

Frank and Captain Robert W. Wood as the Mattaponi nears Bataan Peninsula:

“You know, Pierce,” he says, “this is the day before Christmas.” He looks thoughtful, musing for a while before continuing. “But I guess it’s a better one than those poor guys spent out here five years ago.”

“Yes sir. I guess it is.” My voice is soft.

“I had a brother out here then,” the captain says. “He was a major in the Army. He was killed. Some plane laid a bomb almost on top of him, I guess.” He stops for a little time again.

I know what he is going to say next because he has told me about his brother once before and has probably forgotten that he has ever mentioned it. He is going to fill me in again about his brother.

“I’m sorry, sir,” I say.

“I’d like to find his grave while we’re in this time,” the captain muses. “Last time I was here was before the war.” He is not looking at me as he speaks. He is looking at the heaving sea.

“Yes, sir. We’ll make it,” I say. “We ought to get in about two hours after dark tomorrow.”

“Damn them!” says the captain, suddenly angry. “Damn them!”….

Frank’s shipboard reflections on Bataan:

I look at the land. We are coming in from the west toward a steadily heightening peninsula—Bataan. The Bataan peninsula. So this is where MacArthur fought and the Japs had their great day. This is the place where the U. S. lost a lot of guys and a lot of material. This is the peninsula where the Death March took place. This is what men fought for, and the captain’s brother had died someplace on, and we are now taking bearings on. This blue, hazy wall in the distance, twenty miles away, toward the rising night, high and rugged in two places, then lower in the center. This is it, and I am seeing it. To the left is Subic Bay, where the mountains fade into nothing, and left of that is the north-stretching island of Luzon idling towards Lingayen Gulf.

And far away, just on the horizon, is a speck, a little low mound, a blue island like all blue islands—only this one is named Corregidor. And to the right even more, to the south, the southern part of Luzon beyond Manila Bay….

The executive officer and Captain Wood comment on Corregidor

“Beautiful,” says the commander. It’s the executive officer, Lieutenant Commander Krupa. He’s speaking to the captain.

“It certainly is,” the captain responds, pointing. “There’s Dougout Doug’s* home. They say he lived in the highest house on the island. It certainly is wrecked. Those buildings to the left were barracks, and those closer over here, too.”

“I see them, captain….”

“You know, it’s a funny thing,” says the captain again softly. “One of the most beautiful sights from Manila is a sunset over Corregidor. But from Corregidor you can never see Manila….”

* Pejorative nickname for General Douglas MacArthur.

I recall the day after we arrived in Manila going up to the flying bridge to look around with my field glasses. I saw a number of sunken ships. The Bay is about 10-15 miles across but not much deeper than 40-50 feet. In the next few minutes I counted more than 400 sunken ships before I quit. And I hadn't even scanned the entire bay. Casualties there had accumulated from the very beginning of the war with little to nothing done to rid the harbor of their hulks. It made careful navigation extremely important to avoid these sunken obstacles. Actually, the ships I could see were those that had sunk and were resting upright on their bottoms. Others that had turned turtle and gone down on either side or their superstructures were not visible easily.

Government building in ruins, Manila, 1946

Captain Wood didn’t command the respect of most of us. As a CO he was rigid, inflexible, narrow. I wrote about him in some detail in my private shipboard journal.

Fortunately, I had the privilege of serving under a fine CO, Captain Henry Jarrell. Captain Jarrell came on board for 10 ½ months, and I served with him part of that time. He was one of the first American military men sent to China to learn Chinese. He was an excellent source of information. He would alert us to what we could expect at various places in Asia, how to get along in Shanghai, and other helpful information. I remember being with him on a visit to the Ginza [shopping and entertainment area in Tokyo]. In a store he read the characters on five pieces of furniture and determined they were Chinese-made. During our stay in Yokosuka, around July of ’46, I recall him saying, “In the next war, the Chinese will be our enemies, and the Japanese will be our friends.”

Excerpts from Frank’s memoir of a visit to Nagasaki on August 19, 1946

…Shortly after reveille on the morning of Sunday 19 August, the Salamonie’s captain inquired of our CO if there were three Mattaponi officers who’d like to join a Salamonie party of 57 officers and men on an all-day train trip to Nagasaki and back. Ensign Armin Richter and I volunteered immediately. We were joined by Ltjg Harold A. Davis, MC, our ship’s doctor. For the three of us, it seemed like a great way to spend what otherwise would be an idle day. The Salamonie’s cooks provided all 60 of us from both ships with bag lunches and canteens of drinking water.

Nagasaki was only 30 miles from Sasebo by air, but by railroad it was a much longer 70 miles. Kyushu Island was extremely rugged in this area. The railroad curved incessantly, and several times the route passed through long, dark tunnels. These harrowing transits proved a disaster as far as everyone’s uniforms were concerned. We found no way to cut off the whistling air vents in our car, which blasted us inside every tunnel with asphyxiating clouds of black smoke from the train’s inefficient soft-coal burning engine. By the third tunnel we were hot, dirty, disgusted, and bedraggled. We finally reached Nagasaki at 1130. There the Salamonie officers freed everyone to roam as they pleased but ordered us to be back to the train station by 1500. [T]he Salamonie officers and men went in one direction while Ensign Richter, Doc Davis and I went in another….

Nagasaki and the contiguous neighboring town of Urakami lay in a sort of bowl surrounded by high hills on every side except one where a long arm of the ocean reached in. Many of the area’s war plants had been located in Urakami close to a small, muddy stream that was moving languidly toward the sea. Several Mitsubishi factories there produced the famous and dreaded “Long Lance” torpedoes which had devastated Allied cruisers as well as other war vessels and civilian ships during the early part of the war.

Dr. Davis, Ensign Richter and I began our tour by making a sort of figure eight around the southern area of the two cities. We looked first at the ruined city hall and a Catholic Church, then swung part way up a hill through a graveyard. By then we were hungry, so we picked a place to eat our lunch of sandwiches and orange sections. That completed, we walked back down into the valley toward the ruined manufacturing plants which we had seen from the hill while eating lunch.

When we got into that area, we found that everything there originally had been almost totally destroyed, burned or crushed….

We went up another hill to see a building which we learned later had been a Medical School. We guessed that it was within a mile of ground zero, and from a distance it looked reasonably undamaged. However, when we reached it and went inside, there were no windows or doors in any inner walls still standing. Instead the floor was partially filled with reinforced concrete masonry, twisted steel fingers of various kinds of medical equipment, broken glass, and great amounts of fine, white-colored dust. Idly, I bent down to the floor in one room to pick up a small fused glass blob. It was dark in color and encrusted inside with cinders. Upon examining it carefully, the three of us concluded that it probably had been a laboratory test tube. Now it had been melted and hardened into a small, dirty, biscuit-like mass. I decided to keep it as my tiny souvenir of the power of the bomb and its fiery aftermath. I still have it today. It did not occur to me at the time to consider whether or not it was still radioactive.

We learned later that this medical school building had employed approximately 300 people before it was destroyed in the blast and the fire which followed. Not a trace of any of them has ever been found. They and much of the building’s contents had simply disintegrated.

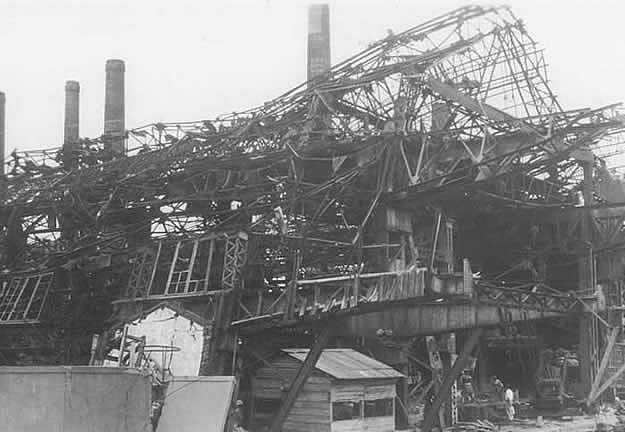

Our final visit of the afternoon was to the major Mitsubishi factory area. If our assessment was correct, these huge war plants were located less than a mile from the bomb’s epicenter. Now they stood as twisted, blackened iron skeletons interwoven with rusting steel beams and sagging metal supports. Each structure remained leaning away from the blast center at angles up to 45 degrees from the vertical. All were totally ruined.

The only features of construction which seemed to have withstood the awesome power of the explosion at least partially were chimneys, many of which appeared almost undamaged. However, we did see other chimneys which were bent halfway up.

Richter, Doc Davis and I found we had little to say to each other during our three-hour tour. We looked at most of the ruins silently, trying to figure out in our own minds what kind of structure had existed there before the plutonium sunburst did its awesome, instantaneous work. Much of the time we had no idea of what we were looking at. As far as the Japanese cleanup efforts were concerned, all we could see that had been accomplished was the clearing of paths past the innumerable piles of rubble plus the building of a number of small, wooden buildings.

Ruined building in Nagasaki. Japanese workers in foreground.

Fairly near the end of our visit, three young Japanese children peaked from behind one of the buildings and regarded us fearfully but also with curiosity. By chance we had not eaten all of our orange slices at lunch. On an impulse, we offered each of the children a slice. They looked intrigued, but made no move to approach us. A moment later a man appeared briefly from behind the building to check on what the children were doing. When he saw the orange slices being extended, he nodded his head quickly to give the children permission to approach us. They did so hesitantly. As soon as each of the orange slices was in hand, they immediately disappeared behind the building again.

We returned to the train station a few minutes before the 1500 deadline and rejoined the officers and crewmen from the Salamonie for the trip back to Sasebo. We talked very little among ourselves during the entire three-and-one-half hour ride. Each of us was thinking about the sights we had seen and going over them again and again in our minds. Unfortunately, the infuriating black coal smoke in the tunnels affected us all and Doc Davis became ill during the ride.

When we reached Sasebo near sunset, we walked eagerly to the ramp where the Salamonie’s boat was scheduled to pick us up …. [A] strong wind came up….It began to blow gravel chips and choking dust over us in a real dust storm. There was no place available where any of us could get out of the stinging wind. Our only defense was to hunker down with our backs to the near gale in the hope that the boat would arrive soon….

By the time the Salamonie’s coxswain and boat crew finally arrived about 2100, everyone from both ships was in an extremely foul mood. We were dusty, gritty, dirty, profane and totally dry-mouthed. Then, when the boat did moor, the coxswain told us we’d have to wait further until he fixed the craft’s bow light….By then everyone from both ships was so angry that they overruled him immediately, piling aboard and shouting at him to get this obscenity craft moving. So the abashed coxswain took off into the dust storm while one of his boat crew stood in the bow swinging a flashlight….

During the ride Doc Davis began throwing up over the side. Fortunately, soon after we left the ramp the wind died, and we had clean air to breathe again….I remember that the first thing I did after helping Doc Davis to his cabin was to take a shower and change clothes. After that I felt considerably better….

Did you or anyone you knew then express the view that the atomic bombing was overkill and there might have been less extreme ways to get Japan to surrender?

I certainly didn’t and I don’t know anyone who did. There was no guilt feeling about the atomic bomb. We wanted to end that war. It had gone on too long and cost too many lives. The feeling was: the Japanese started the war and we’ll finish it.

Besides the Nagasaki visit, what other ways did you spend your off-duty time?

I wanted to put my off-duty time to good use. Many Navy guys just wanted to go to bars and get screwed. I was one of three officers who never did those things. I didn’t smoke or drink. I came into new places, wanted to see new things and cultures, and write about them.

Scenes of Yokohama and Tokyo (from Frank’s letter to his family, August 4, 1946)

…All over the place [Yokohama] are rusted iron scraps of machines, and buildings. Mile after mile is like this, just barren, with junk piles and stone rubble about….It is amazing, and hardly seems as though bombs did it. It just looks as though somebody moved out and tore the buildings down, and let the weeds grow up. For ten miles or so to Tokyo, the scenery is like this….[T]he damage is total; whatever was here is really gone, and nothing will be here for a long time to come. Not a building! It is amazing.

The Japs say all this damage was done in one raid of 300 Superforts [B-29s] with blockbusters and incendiaries. The fires started burning uncontrollably for three days, and the bombers came back each night guided by the fires. I am glad I was not a Jap then.

When we got to Tokyo, we got off at the main station, which is being rebuilt. It was burned out by bombs, and they are reconstructing it again….[T]he Captain said that we should walk down to see the Ginza, which is the main shopping district. We spent about an hour and a half just window shopping. We went into stores (the ones that were still standing, or rebuilt) selling all sorts of things: knick-knacks, jade, star sapphires, paintings, silks, hardware, and anything else anyone would ever need. We priced a piece of jade jewelry at 6,000 yen or $400. We browsed around, took pictures, looked in windows, and had a very good time. Then we looked at all the sidewalk merchants and their wares. The sidewalk merchants here were at least clean; over in Shanghai they were filthy….

We wanted to see Hirohito’s palace. It was only a couple of blocks down the drag the other side of the railroad station from the Ginza. We walked around two sides of it, but could see nothing outside the moat and high wall which entirely surrounds it. All the gates were guarded by Allied MPs, and there is absolutely no admittance to anybody…. Most of Tokyo is not leveled, but only burned out. Walls tower up but there are no roofs, or anything inside. A great portion of the city is this way….

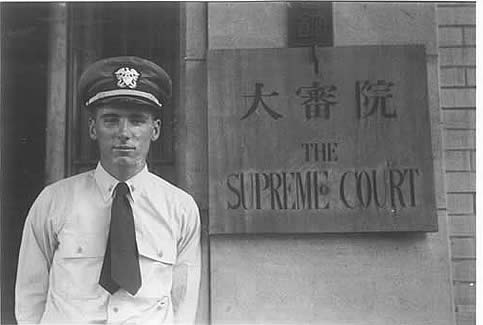

Here’s a picture of me in front ofthe Supreme Court Building in Tokyo where the war crimes trials were held. It was closed the day this picture was taken; I wasn’t able to get back to Tokyo to see inside it.

In a Yokosuka geisha house (from Frank’s letter to his family, November 13, 1946)

Several evenings ago six of the ship’s officers and myself [sic] went to a geisha house for the evening. Please do not get the idea that a geisha house is the equivalent of a prostitution house in the U. S., for it is not at all. The geisha girls are members of one of the best occupations in Japan. These women have advanced to the highest standing they can achieve over here.

The geisha house is run by Mama San, a woman that [sic] used to live in Oakland for 16 years. She has been back in Japan for the last 18 years, so her English is not too good, but she still understands us and we can talk to her. That is quite fortunate, since the girls themselves speak only a few words of English….The house is very nicely constructed, although of rather frail build. There is no heat that I could find, with the result that it is chilly. First we ate at a long low table, perhaps a foot and a half off the floor. We sat on cushions, drank cokes, and talked with the girls as much as possible while the meal was being cooked. The meal (we had taken the precaution to eat well on the ship before we left) was cooked over coals at one end of the room, and was finally finished. So we ate with chopsticks as well as possible a dish called sukiyaki….

It was strange tasting stuff. It seemed to be the bodies of very young birds that had been hardened somehow. Not very appetizing at all, I thought. But I ate some and tried to learn how to use chopsticks….

The girls knelt down beside us in their flowery kimonos and drank cokes and ate the stuff as though they relished it. They also saw to it that our glasses were never empty of coke, service which rather gripes me because I hate to have anyone hover over me when I eat. But it is the custom for the women to wait on the men hand and foot....The other officers had brought along some whiskey, and they drank this with their cokes. I did not have any of this. However, the girls drank it right down as if they subsisted solely on alcohol. Only one of them got drunk, but two of our officers were quite drunk after an hour or so. One of them just lay around and went to sleep afterwhile [sic], while the other lay around on the floor pinching the girls who came near. It was quite disgusting to me to see a grown man make such a fool of himself.

After the sukiyaki, there were dances by the geishas. They did the customary bowing to each other, to the accompanyist [sic], to the guests, and then started their dance. The dances were strange, with the dancers cutting figures and poses such as you have seen in pictures….

The doctor [Harold Davis] and I asked Mama San about things interesting to us and she told us a great deal. She told us a story of a couple of the dances, how the conditions were in Japan during the war, and answered other innumberable [sic]…questions for us.

We had brought along a few records and played them on the phonograph for American-style dancing. The girls were good dancers, but it is hard to talk to them. So everyone just danced about in silence.

About midnight we were ready to leave, after a pleasant evening….

Love to all, and I’ll be seeing you sometime next year.

Frank

Let’s conclude with some information about your wife and family.

I met Jo Ann Bell of Dilley, Texas, in late 1949 when we both were in the University of Missouri’s Graduate School of Journalism. We married in 1951 after she received her M.A. degree. She worked as a writer for a national agricultural magazine when we lived in Cincinnati (1951 – 1953). During our years in Houston and California, we were in the “baby business”—four children in six years. At the University of Illinois, Jo Ann worked full time as a writer in the university’s agricultural office. Her earnings allowed me to continue my doctoral studies at Illinois. After we moved to Florida, she spent 22 years as a full-time writer, editor and professor in the Institute of Food and Agricultural Science at UF. In 1984 she was elected the national president of Agricultural Communicators in Education, only the third woman ever selected and the second person from the state of Florida. In 1996 she retired from UF as a professor emerita.

We have two sons and two daughters. Each has at least two university degrees. Our first son works in Miami as a translator for EFE, the Spanish news agency headquartered in Madrid, Spain. Our second son is a computer programmer in the Washington, D.C. area. One daughter is a librarian here in Gainesville. The younger daughter is between jobs just now. We have five grandchildren.

|